Armenian-Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh is considered one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 20th century.

Karsh’s portraits are easily recognizable for their bold and theatrical use of lighting, closely cropped composition, and his uncanny ability to reveal the inner-self of his subjects.

Over his 60-year career, Karsh photographed more than half of the International Who’s Who Millennium list of the 100 most influential figures of the twentieth century and was also the only photographer included in the list.

Schooled in the Hollywood glamour tradition and specializing in classical portraiture, Karsh traveled all over the world to photograph political and military leaders, as well as celebrated writers, entertainers, and artists.

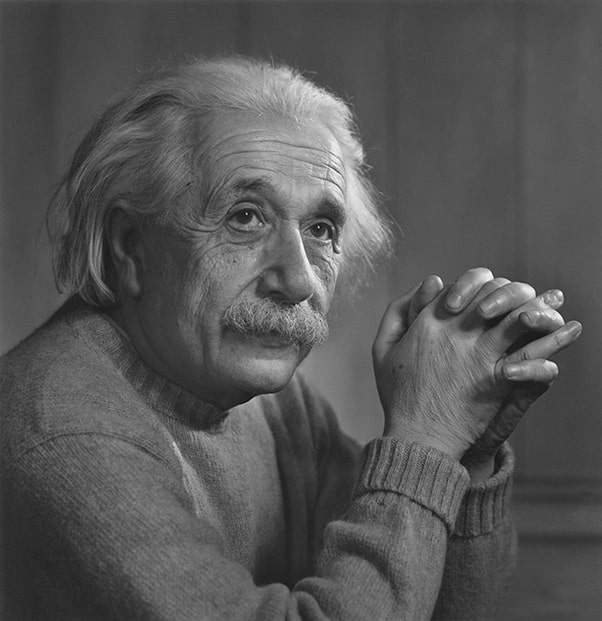

By the end of his career, Karsh of Ottawa, as he was called, had achieved a rare stature: His portraits had become the images by which many politicians and cultural figures are best remembered – Winston Churchill as an indomitable wartime leader; Albert Einstein with his hands clasped together; Humphrey Bogart with a burning cigarette in hand.

When the rich and famous start thinking of immortality, they call for Karsh of Ottawa.

George Perry

In his lifetime, Karsh held a remarkable 15,312 sittings and produced more than 370,000 negatives, leaving an indelible record of the women and men who helped shaped the twentieth century.

Related: 28 Yousuf Karsh Quotes for Better Portrait Photography

Within every person a secret is hidden, and as a photographer, it is my job to reveal it if I can. The revelation may come in a fraction of a second in the form of an unconscious gesture, a gleam of the eye. In that fleeting moment, the photographer must act or lose his prize.

Yousuf Karsh

Table of Contents

Yousuf Karsh Biography

Name: Hovsep Karshian

Nationality: Armenian-Canadian

Genre: Portrait, Fine Art

Born: 23 December 1908

Died: 13 July 2002 (93 years old)

Early Life

Born Hovsep Karshian in Mardin, a Turkish city of the eastern Ottoman Empire, Karsh grew up during the period of the Armenian Genocide.

In 1924, at the age of 16, his parents sent him to stay with his uncle George Nakash, a photographer who lived in Quebec, Canada.

After barely six months of high school, Karsh left formal education and began working full-time with his uncle, providing him with income to support his family back in Syria.

After a few years assisting his uncle, Karsh, who by now was twenty, was sent to Boston to apprentice under the respected portrait photographer John H. Garo in 1928.

Fellow Armenian Garo encouraged Karsh to attend evening art classes to study the old masters, specifically Rembrandt and Velázquez.

While assisting Garo, Karsh learned about the importance of light, shadow, and form. These three elements would become key to his work.

Karsh would later regard Garo as the most important influence on his early career.

First Studio

In 1931, Karsh returned to Canada and opened a studio in Ottawa, close to the Canadian Parliament building.

He initially undercut his competitors, charging one dollar for a finished print with his much of his early work mainly consisting of passport photos, family portraits, business events, and weddings.

He also photographed actors at the Ottawa Little Theatre, where he was introduced to the potential of theatrical lighting, as well as to the elite classes of Ottawa.

While working with the theatre, Karsh met the French actress, Solange Gauthier, who he would later marry in 1939.

His first major commission came from the Governor-General and Countess of Bessborough, who he first met at the Little Theatre.

Karsh was quickly acquiring the reputation as an outstanding portrait photographer whose lighting magic flattered his subjects. In demand, his client list included many high-achievers in politics, the arts, and the world of show business.

My chief joy is to photograph the great in heart, in mind, and in spirit, whether they be famous or humble.

Yousuf Karsh

In 1936, Karsh was invited to photograph President Roosevelt, the first American president to officially visit Canada. He traveled to Quebec for the sitting, where he also met Prime Minister Mackenzie King who would facilitate the famous portrait of Winston Churchill.

Sir Winston Churchill

In 1941, at the age of thirty-three, Karsh immortalized the great Sir Winston Churchill on film.

Churchill was visiting Washington D.C. and Ottawa with hopes of persuading both the U.S. and Canada to contribute to the war effort.

The Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King invited Karsh to House of Commons to watch Churchill’s speech and then to photograph him.

Following his speech, Churchill was directed into the Speaker’s Chamber where Karsh had set up his equipment. Unaware of the planned sitting and in no mood to have his portrait taken, Churchill marched into the room scowling with a cigar stuck between his teeth. He allowed the photographer just two minutes to get his photograph.

Karsh asked him to remove the cigar and when he refused, the photographer instinctively walked up to the great man and removed the cigar himself. Churchill scowl deepened, and he thrust his head forward in anger and Karsh got his photo.

The image captured Churchill and the British spirit during World War II perfectly – defiant, tenacious, and unconquerable.

It’s a story that has been dramatized by the press a great deal… I photographed Churchill three times, twice after that occasion. It was a spontaneous act on my part (removing the cigar). It was similar to picking a piece of thread off your shirt. It was done with respect and appreciation. But he responded. His expression, although not planned on my part, fit the need of the hour.

The Most Reproduced Portrait in History

The portrait which was later published as a cover for Life magazine, went on to become the most reproduced portrait in history, appearing on the British 5-pound note and various stamps through the years.

However, Karsh’s favorite photograph from the sitting was taken immediately after.

Impressed with the audacity of the photographer, Churchill allowed Karsh to take one more photograph for which he smiled. After the sitting, Churchill remarked to Karsh, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed”.

It should be the aim of every photographer to make a single exposure that shows everything about the subject. I have been told that my portrait of Churchill is an example of this.

Yousuf Karsh

Faces of Destiny

The Churchill portrait was a turning point in Karsh’s career and catapulted him into international fame.

To show that Canada was playing a part in the war, Karsh sent to London by the Canadian government in 1943 to photograph the other leaders of wartime Britain. During the trip, Karsh took portraits of the British Royal Family, George Bernard Shaw, and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

This was followed by an assignment for Life magazine to photograph the American war leaders.

By the end of the war, Karsh was known throughout the world as a sympathetic portrayer of the famous and powerful. His first book, Faces of Destiny which was published in 1946, features his iconic portraits from the period.

In the next chapter of his career, Karsh’s interest moved from political figures and statesmen to Hollywood stars, musicians, philosophers, businessmen and athletes.

Karsh and the 1950s

In 1952, Karsh took on an assignment for Maclean’s magazine to photograph the economic development in post-war Canada.

For the project, Karsh traveled throughout the country to photograph the cities and workers. Over seventeen months, the photographer shot over 8,000 negatives, with Maclean’s publishing 280 of them in their magazine feature.

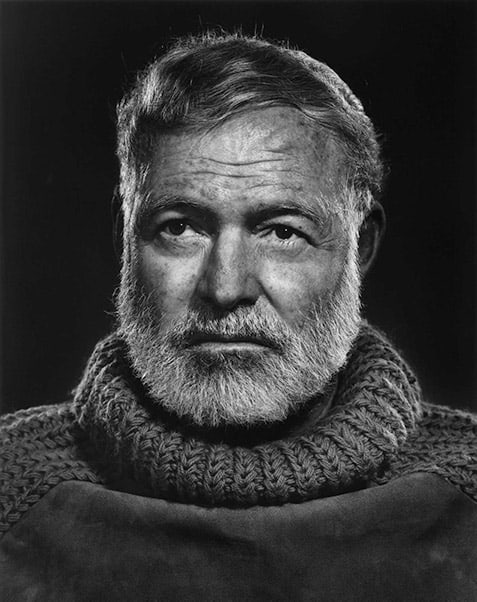

By the late 1950s, Karsh had become just as famous as his sitters. During the decade he photographed celebrities including Audrey Hepburn, Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, Alberto Giacometti, and Georgia O’Keefe.

Karsh’s success came at a price though and in 1959 he suffered a heart attack due to over-work. The same year his mother died and his wife Solange was diagnosed with cancer – she would die two years later.

In 1960, Karsh’s portraits were exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada, while his second book, Portraits of Greatness, sold out before the press events for its release.

Karsh re-married in 1962, this time to a historian and medical writer, Estrellita Machbar, who he met during a portrait session in Chicago.

Later Career

In 1987, Karsh sold his archive, including all his negatives, to the National Archives of Canada, where his former apprentice, Jerry Fielder, became the curator of the collection.

Karsh continued to work throughout the 1980s and into the early 90s. One of his most successful photographs from his later career is a double portrait of the American president, Bill Clinton, and his wife, Hillary.

The Karsh studio closed in 1992, by which time the legendary photographer had snapped portraits of every Canadian prime minister since Mackenzie King, every British prime minister since Sir Winston Churchill, every French president since Charles de Gaulle, and every U.S. president since Herbert Hoover.

Karsh and Estrellita moved to Boston in 1997, taking up residence in an apartment close to the Museum of Fine Arts. Karsh donated 199 portraits to the museum’s permanent collection.

In 2001, Karsh was included in the International Who’s Who list of the 100 most influential people of the twentieth century. Karsh was the only Canadian, and the only photographer, on the list.

Karsh died in Boston on 13 July 2002, at the age of 93 after complications following surgery.

Legacy

Karsh’s archive includes 50,000 original prints, 260,000 negatives, and color transparencies. Many of his great portraits can be viewed on the official Yousuf Karsh website.

His books include The Faces of Destiny, In Search of Greatness: Reflections of Yousuf Karsh, Karsh Portfolio, Karsh Portraits, and Karsh: A Fifty-Year Retrospective.

Karsh’s portraits are in the permanent collections of several of the world’s best art museums, notably the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and many others.

He received numerous honors and awards in his life including the Canada Council Medal (1965), Officer of the Order of Canada (1967), Medal of Service of the Order of Canada (1968), Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society (1970), United States Presidential Citation (1971) Gold Medal of the National Association of Photographic Art (1974), Achievement and Life Award, Encyclopedia Brittanica (1980) and Companion of the Order of Canada (1990).

Karsh was also awarded numerous honorary degrees from Canadian and American universities.

Karsh’s Photography Style

- Environmental portraiture

- Formal, posed

- Black and white

- Artificial lighting, theatrical

- Simplicity

How to Shoot like Karsh

Karsh was a master of the formally posed, carefully lighted portraits. He often said that the most important lesson he learned early in his career was that the art of photography was a combination of observation and intuition.

Okay, aside from observation and intuition which comes through experience, what else can we learn from Karsh’s experience.

Here are 3 more lessons from Yousuf Karsh, which everyone can use to take their portrait photography to the next level:

Lesson 1 – Do your Homework

Before Karsh met with his subject, he’d study up. He’d learn as much about them as he could and, if possible, even observe them at work.

It was in London that I started the practice which I continue to this day of doing my homework,’ of finding out as much as I can about each person I am to photograph.

Yousuf Karsh

On the day of the shoot, despite being focused on the technical side of his work, Karsh used the information he had learned to keep the conversation between him and his subject flowing.

To make a significant photo of someone, you have to know a great deal about them —their accomplishments, mission in life, or contribution to their fellow man. All this information and observation plays an important part so that the photographer can make a sensitive image.

Yousuf Karsh

When asked how he puts his subjects at ease, Karsh responded:

I do a great deal of reading about them or information I have if they’re not authors, and if they’re in the public eye then the work is being done for me. I go after having done all this preparation, I go with [an] open mind. Usually, these great men and women, are in the habit of giving much of themselves to you, so that much of your preparation may totally be unused at the time but you feel you are well-armed.

Lesson 2 – Environment, Visual Clues, and Framing

Karsh preferred to photograph his subjects in their own environment, with many of his portraits shot against simple backgrounds (frequently black.)

Karsh’s portraits often incorporated visual clues and he would look out for body language – hand gestures, facial movements, and direction of gaze – to bring out the personality of his subjects. He only used props that would enhance the image and help tell the story of the subject.

He also wasn’t against cropping his images if it made for a better portrait.

I do not attribute any special virtue to cropping or lack of cropping because when you write a book, you don’t care to tell the world that this was written on the first draft, there’s no merit in that. The merit is, what is the final result.

Yousuf Karsh

Lesson 3 – Take Charge

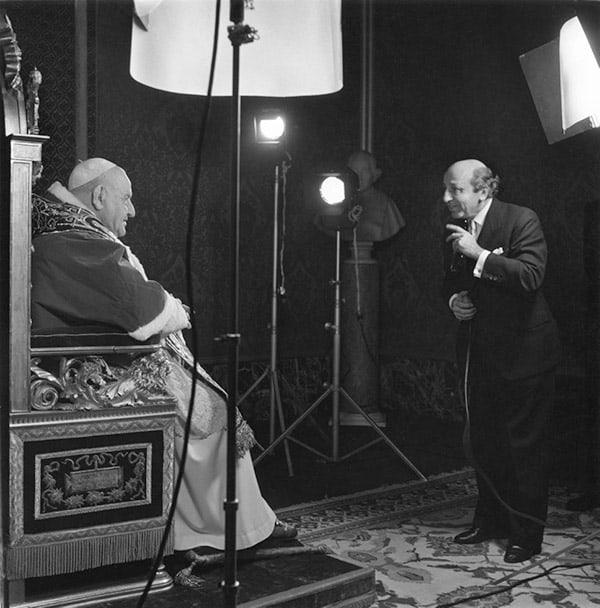

Karsh was in charge, no matter his subject, and he chose the locations and set-ups and even placed all of his sitters himself.

To help build a better rapport, Karsh worked with only one assistant, whether traveling to location or in the studio – there were no hairstylists, make-up artists, or managers allowed – it was only him and his subject.

Related Article: 150+ Portrait Photography Quotes

Once the lighting (see the section below) and composition were to his satisfaction, he would leave the camera and engage with his subject, ready to squeeze the shutter release in his hand and capture the moment of truth.

When one sees the residuum of greatness before one’s camera, one must recognize it in a flash. There is a brief moment when all that there is in a man’s mind and soul and spirit may be reflected through his eyes, his hands, his attitude. This is the moment to record. This is the elusive “moment of truth.”

Yousuf Karsh

If any of his negatives showed his sitters looking cold, and the image he wanted to portray wasn’t revealed by the camera, then he simply refused to print the negative.

I am satisfied that no purpose would be served if I were consciously seeking to convert what would be a portrait of greatness into a moment of weakness. Such moments are not worthy of recording.

Yousuf Karsh

Yousuf Karsh Lighting

Of all the technical aspects of photography, Karsh was the most interested in lighting. He became a master of light and consistently employed artificial lighting in his studio and on location throughout his career.

Although Karsh likely used some light units at his uncle’s studio, he didn’t experiment with artificial lights until the early 1930s. His mentor, John Garo worked only with natural light in his studio in Chicago.

Karsh was particularly interested in theatrical stage lighting and learned new techniques while working with Ottawa’s Little Theatre. Karsh found artificial lighting both fascinating and challenging; he wanted to master it and make it work for him.

Karsh’s Lighting Process

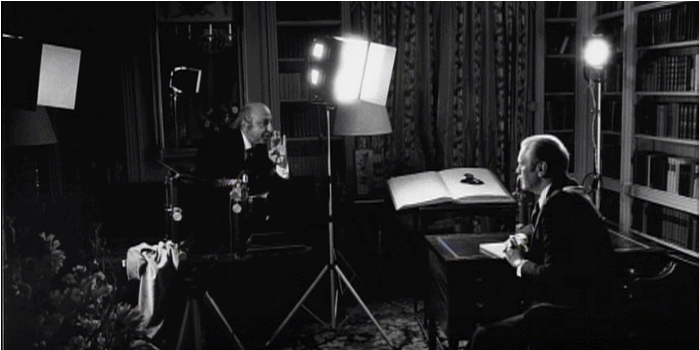

Karsh always had an assistant set-up the lighting and camera equipment for him. First, the assistant checked all bulbs, and placed the main and fill lighting units in a standard arrangement.

The assistant would then assemble the backdrops: large backdrops were placed behind the subject’s chair and smaller screens near the edge of the large backgrounds.

Hidden between the screens or directly behind the subject was a small one bulb light that illuminated the background and separated it from the subject.

The backlight came with two fiberglass cloths. One or both cloths, fitted on a metal diffuser, were placed over the light to soften it as required.

After setting up the main, fill, and backlights, Karsh’s assistant placed one spot light on each side of the subject. Close to the spots were two stands, which supported handmade, black cardboard cards.

These cards were fitted with a hook, which resembled a coat hanger, and revolved 360 degrees on the stand. These were mainly used to block light from shining into the camera lens.

Once all the lights were set up, Karsh would check everything for himself and examine the stage. He would then test the lighting setup, with his assistant standing in as the subject.

I would always set up the lights and camera in the same way so he knew instinctually where everything was. It was like an artist who places paints in the same order on his palette to concentrate fully on the canvas. Yousuf would then make adjustments as the sitting progressed – sometimes minor, sometimes major, but never the same.

Jerry Fielder, from Karsh: Beyond the Camera

After his initial test, Karsh would re-arrange the lights. He might switch the main and fill units around, with the main on the left side, and the fill on the right of the sitter, or he might remove the fill light altogether. He might turn on one spot light, or keep both off during the entire session.

Karsh’s final lighting always depended on the atmosphere of the session and the mood of the sitter. Likewise, he applied different light formulas for both men and women.

When Karsh photographed women, he always used softer light and turned the main and fill units slightly away from the subject, directing the spot lights on the hair or shoulders to reduce the appearance of wrinkles or facial lines.

Karsh Light

During a typical photo session, Karsh’s main key light was placed slightly behind the camera and about one and a half meters to the right of the camera.

Karsh always placed two lights behind his subject on both sides – to act as either fill or rim lights – which resulted in light bouncing off the side of the subjects face and towards the camera.

This setup provided highlights to both sides of the subject’s face, with the center of their face slightly darker. Depending on the sitter, Karsh might also place another light (to act as fill) on the opposite side to the key light on the left side of the camera.

Another unique Karsh lighting trait was to light the subject’s hands with a separate light. There is a lighting pattern named after him “Karsh Light” which uses a fifth side-light, in addition to the four standard lights described.

Related Article: Horst P Horst: The Photographer of Style

Karsh’s Lighting Equipment

Karsh preferred tungsten lights (5 x 250W white ECA photoflood bulbs with a color temperature of 3200K) because he could see the results on his subject’s faces (many other fine portrait photographers prefer tungsten lights for the same reason including Peter Lindbergh and Herb Ritts).

He also found Tungsten lights to be less disruptive than the flash of strobes, which allowed him to build a better rapport with his subjects. He used hot lights with a bulb release (so the subjects couldn’t see when he was about to squeeze the shutter).

Although he had a dislike for flash lights, he could also see the benefits and used them on assignments in Europe and the U.S.

I use electronic flashes, scopic lights when I’m in Europe and at times in the United States, but I prefer working with tungsten lights, [both] floods and spots, but in Europe because of the problem with strong enough electricity, I use electronic flash strobes.

If you want more information and a detailed breakdown of Karsh’s lighting equipment, then we recommend checking out the following article Lights, Camera, Personality: The Karsh of Ottawa Collection

What Camera Did Yousuf Karsh Use?

- Calumet C1-8 x 10 with interchangeable 8 x 10 and 4 x 5 film backs

- 14″ Commercial Ektar lens

Karsh experimented with cameras early on in his career before settling on Calumet large format cameras in the 1940s.

Karsh’s main camera was a Calmet C-1 8×10 made in 1956, which he used for more than three decades. The Calumet was typically used by Landscape photographers of the day and rarely seen inside portrait studios.

Attached to the Calumet was a 14″ Commercial Ektar (350mm) lens, the equivalent of around 55mm in 35mm photography.

With his trusty Calumet, Karsh photographed many of his classic portraits including Ernest Hemingway, Ronald Reagan, George Bernard-Shaw, Mother Teresa, and many other personalities.

Printing Process

The majority of Karsh’s portraits were shot using black and white film and developed by inspection by Karsh and later his printers.

Karsh mixed developers to his own formulae. When it came to working with negatives, he used specialist chemicals that allowed a faint green light to reveal the deepening densities so he could judge each one individually.

For prints, he had two developers: hard and soft. Although many times, he would use both on the same photograph – one to bathe the print and the other applied carefully in specific areas with a cotton bud.

I don’t expect that many of his negatives were under-exposed, but he likely targeted the shadow, mid-tone and highlight rendition that differs significantly from what might be considered “normal” by today’s standard.

Karsh’s color portraits from the 1950s were dye transfers completed through a printer in New York.

Other Resources

Recommended Yousuf Karsh Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Yousuf Karsh: Heroes of Light and Shadow (2001)

- A Biography in Images (2004)

- Portrait in Light and Shadow: The Life of Yousuf Karsh (2008)

- Karsh: Beyond the Camera (2012)

Yousuf Karsh Videos

Karsh is History: Photographing Icons (2010)

This is probably the best Yousuf Karsh documentary available today. As of 2020, the full documentary is available to watch for free on Amazon Prime

The Searching Eye (1986)

Connie Martinson Talks Books: Yousuf Karsh

Terry Wogan: Yousuf Karsh Interview, BBC (1988)

Yousuf Karsh Photos

In his career, Yousuf Karsh took an incredible 15,000 portraits. To view a huge selection of his portraits, head over to the official Yousuf Karsh website

Fact Check

With each Photographer profile post, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Karsh’s work and his life then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through your blog or social media.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us either Instagram and Twitter (or both) to receive regular updates on new blog posts.

Recommended Yousuf Karsh Links

Want to learn more about Karsh and see more of his great photos then visit the official Yousuf Karsh website at karsh.org. Don’t forget to explore other areas of the website including the videos section.

Other master portrait photographers:

Sources

Karsh: 50 Years of Photographs by Yousuf Karsh, National Portrait Gallery, 1984

Yousuf Karsh: Heroes of Light and Shadow, Stoddard, 2001

Yousuf Karsh Biography, Official Website

The Daily Telegraph Obituary, 2002

Armenian who became portraitist of the famous, The Irish Times, 2002

New York Times Obituary 2002

Karsh: A Biography in Images. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2003.

Karsh: Beyond the Camera

Karsh: A Fifty-Year Retrospective, 1983

Portrait in Light and Shadow: The Life of Yousuf Karsh

Karsh: In Search of Greatness

Terry Wogan Interview, BBC, 1988

Karsh is History, 2010