Hiroshi Sugimoto has over the years become one of the most critically acclaimed artists and photographers of his generation.

The Japanese photographer emerged in the ’80s as one of the best of a new generation of artists, including Andreas Gursky, Cindy Sherman, and Jeff Wall, who transformed the medium of photography from a craft into a major art form.

Sugimoto’s works are made up of several series with each one being distinctive in theme.

He is perhaps best known for his ongoing series of photographs of cinema interiors, of seascapes, and of dioramas from the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

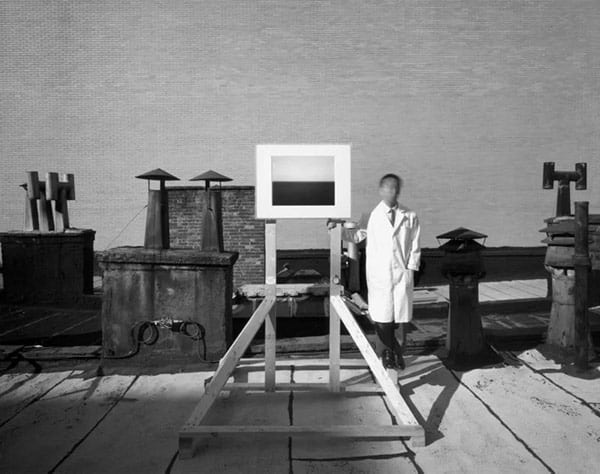

Using a large-format camera and often exposing his negatives for several hours, Sugimoto produces images with striking visual clarity that provide a mesmerizing meditation on the nature of time.

Sugimoto has spoken of his work as an expression of “time exposed”, or photographs that compress long expanses of time into a single frame, serving as a time capsule for a series of events.

Sugimoto is one of the most interesting and visionary photographers working today.

In this article, we’ll try to cover his incredible body of work and the methods he used for creating his images.

Related: 30 Hiroshi Sugimoto Quotes on Conceptual Photography and Time

If you find the article helpful then we would be grateful if you could share it on your own blogs and social media accounts.

Photography is like a found object. A photographer never makes an actual subject; they just steal the image from the world… Photography is a system of saving memories. It’s a time machine, in a way, to preserve the memory, to preserve time.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Table of Contents

Hiroshi Sugimoto Biography

Name: Hiroshi Sugimoto

Nationality: Japanese

Genre: Fine Art, Conceptual

Born: 23rd February, 1948 – Tokyo, Japan

Born in Tokyo on the 23rd of February in 1948, Sugimoto began his photography journey at the age of twelve when his father gave him a Mamiya 6 medium-format camera.

Sugimoto didn’t consider photography as a career until he was in his early 20’s and instead studied politics and sociology at Rikkyo University, Tokyo.

After graduating, Sugimoto traveled abroad, visiting Poland, Western Europe, the Soviet Union, and the U.S.

In 1971, he studied commercial photography at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, near Los Angeles.

While studying at the college, Sugimoto noticed that many of the students had an interest in Zen Buddhism. After realizing that his interest in foreign cultures had led him to neglect his own Japanese culture, Sugimoto began to study Eastern philosophy and Zen.

I came to California in 1970 and so many people were asking if I was a Buddhist or knew Zen theory, asking if I was enlightened already or not. So I said, “Yes, I am enlightened,” and then I studied quickly to catch up.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Zen Buddhism would play an important role in Sugimoto’s work throughout his career.

While in California, Sugimoto trained as an artist and received his BFA in Fine Arts at the Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles in 1974. He then returned to Japan for a few months before moving to New York in late 1974.

Photography Career

In New York, Sugimoto worked as an assistant to various commercial photographers; he would later describe these jobs as ending in mutual dissatisfaction.

Sugimoto spent most of the late 1970s and early 1980s visiting shows at small galleries in Soho and considering his own relationship to contemporary art. During this time, he met artists central to the minimal and conceptual art movements.

Sugimoto has described his process of artistic exploration in this period as relatively slow. It should be noted though, that the ideas for many of his best-known series were formed in these years:

In 1976, he began to take photographs at the Museum of Natural History; these images would lead to his first major series of photographs, Dioramas.

Sugimoto took his first images for Theaters in ’78, this was quickly followed by Seascapes in 1980.

Sugimoto would continue to expand on these series over subsequent decades.

In 1979, Sugimoto and his wife opened a Japanese antique shop, which initially specialized in Japanese folk art, but grew to include a rare collection of Eastern antiquities. The shop provided an independent source of income and a space that could be used as a darkroom.

Recognition

Sugimoto was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1980 at the age of 32. The following year, he had his first solo exhibition at the Sonnabend Gallery, New York.

Despite his growing success, Sugimoto continued to run his antique shop until 1989.

After he closed the shop, he collected antiques for himself and began incorporating these and other objects into his work.

In 1995, Sugimoto had a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This show led to greater recognition, which provided Sugimoto with the financial means to expand his artistic practice.

Today, Hiroshi Sugimoto divides his time between Tokyo and New York, continuing to perfect his photography craft while working on new photography and architecture projects.

His photographs are in the collections of some of the most prominent museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate Gallery, London; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and many others.

Sugimoto has been represented by Pace Gallery in New York, since 2010.

Sugimoto’s Photography Series

Like many great artists, Sugimoto works in series. Below we cover some of Sugimoto’s most popular series of photographs in more detail:

Dioramas

In 1976, Sugimoto’s began his Dioramas project – a series which captures prehistoric scenes of life on display from popular natural history museums across the United States.

The final collection includes a polar bear floating on an ice cap, exotic monkeys in the jungle, and vultures fighting.

The Diorama sessions were initially conducted at the American Museum of National History – a location Sugimoto revisited in 1982, 1994 and 2012.

While many of Sugimoto’s early silver gelatin prints – including Polar Bear (1976), his first photograph from the Diorama series – present animals, a number of his images from 2012 including Olympic Rain Forest and Mixed Deciduous Forest focus on natural landscapes.

How the Series Started

While looking at one of the dioramas, Sugimoto randomly closed one eye. He then realized that by looking at something with just one eye, he flattened the entire scene, making it look just as it would if photographed with a camera lens.

Sugimoto returned to the museum with his camera and took some black and white photographs of the dioramas. What surprised Sugimoto most about the series was that his photos look like they were shot on location, and not in front of a three-dimensional representation of a real location.

The stuffed animals positioned before painted backdrops looked utterly fake. Yet by taking a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished, and suddenly they looked very real. I’d found a way to see the world as a camera does. However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

This visual trick launched Sugimoto’s conceptual exploration of the photographic medium, which continues today.

The belief by many that photography always show the truth and the camera doesn’t lie, tricks viewers into assuming the animals in the photos are real until they examine the pictures more closely.

The Diorama series became the first of many bodies of work in which Sugimoto has rephotographed something, or taken photographs of something that is fake, such as figures in wax museums.

Photography is making a copy of reality, but when it is photographed twice it goes back to the reality again. That is my theory.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Portraits

Sugimoto’s later series titled Portraits, is based on a similar concept.

The 1999 project, which was funded by the Guggenheim Museum in Denmark, captures wax figurines of famous people throughout history based on their portraits from the 16th century.

These photos were done at Madame Tussaud’s in London and Amsterdam as well as a wax museum in Ito, Japan.

For the series, Sugimoto took three-quarter view photos, using 8-by-10-inch negatives, of the most realistic looking wax figures at the museums. The photos were mostly shot against a black background, with the lighting positioned to match the lighting that would have been used by the painter at the time of the original portrait.

Theaters

Theaters is considered one of the first photographic collections to successfully capture time in motion.

In 1978, Sugimoto began photographing old movie palaces and drive-ins with a folding 4×5 camera and tripod. His exposure time for each image lasted the entire length of the movie.

One night I thought of taking a photographic exposure of a film at a movie theatre while the film was being projected. I imagined how it could be possible to shoot an entire movie with my camera. Then I had the clear vision that the movie screen would show up on the picture as a white rectangle. I thought it could look like a very brilliant white rectangle coming out from the screen, shining throughout the whole theatre. It might seem very interesting and mysterious, even in some way religious.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

The result was an extraordinary collection of surreal black and white images.

By capturing every frame of the movie on a single frame of film, Sugimoto manages to capture the passage of time and raise questions about what is real and what is fiction.

Repetition

When the shutter is left open for the duration of the movie, the camera captures every still image as it flickers into existence, resulting in a photograph of a blank, illuminated screen.

The machine has seen everything, yet it seems to have recorded nothing.

Every photo is composed with the screen in the middle of the frame, with the bright light revealing the surrounding architecture, whilst looking like a time portal from another dimension.

My dream was to capture 170,000 photographs on a single frame of film. The image I had inside my brain was of a gleaming white screen inside a dark movie theater. The light created by an excess of 170,000 exposures would be the embodiment or manifestation of something awe-inspiring and divine.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

For the series, Sugimoto photographed more than 100 movie houses and drive-in theaters over a period of four decades. In the last decade, he has expanded on the project and has taken photos of Italian opera houses and abandoned theaters.

Different movies give different brightnesses. If it’s an optimistic story, I usually end up with a bright screen; if it’s a sad story, it’s a dark screen. Occult movie? Very dark.

Seascapes

In 1980, Sugimoto began working on one of his most popular photographic collections, Seascapes.

The series consists of 220 black and white photographs of the motionless ocean. Every photo is perfectly balanced – half water and half air, with the horizon line in the center of the frame.

Humans have changed the landscape so much, but images of the sea could be shared with primordial people. I just project my imagination on to the viewer, even the first human being.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

His photographs freeze time; stills movement, and in some cases transforms the seascape into an unrecognizable abyss.

When looking at the images, you can’t help but be drawn into the open vista, and to question and reflect on the concept of time and place.

Mystery of mysteries, water and air are right there before us in the sea. Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home; I embark on a voyage of seeing.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

The images were taken at various hours of the night and morning and always from the same perspective with the sky and the water meeting on the horizon.

The Master of the Long Exposure

Sugimoto used an 8×10 large format camera for the series, often using prolonged exposure times in order to produce flat and clean images in which the ocean has permanent creases rather than ripples and waves.

While most photographers consider long exposures anything between 30 seconds to 5 minutes, Sugimoto would keep the shutter open for up to three hours to capture his image.

Sugimoto started the series with the English channel, and then photographed the Arctic Ocean, Positano, Tasman Sea, Vesterålen, the Black Sea, and the Norwegian Sea.

The photos from this series are usually displayed in groups of three, further emphasizing the universality of the ocean.

In 1996, Sugimoto’s Baltic Sea – which was part of an edition of 5 – sold at auction for $382,730.

Architecture Work

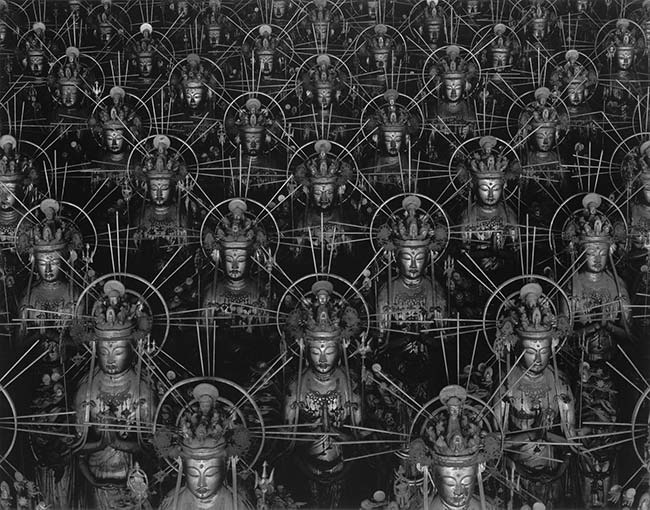

In 1995, Sugimoto photographed the Sanjūsangen-dō (Hall of Thirty-Three Bays) in Kyoto.

After seven years of red tape, I was at last granted permission to photograph in the temple of Sanjusangendo (Hall of Thirty-Three Bays). I had all late-medieval and early-modern embellishments removed, and the fluorescent lighting turned off, to recreate the splendor of the thousand bodhisattvas glistening in the light of the morning sun rising over the Higashiyama hills — as the Kyoto aristocracy might have seen them in the Heian period (794-1185). Will today’s conceptual art survive another 800 years?

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Sugimoto shot the series from a high vantage point and edited out all structural features, so the resulting 48 photographs focused on the thousand of bodhisattvas (life-size and almost identical gilded figures carved from wood in the 12th and 13th centuries) shown inside the building.

In 1997, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago commissioned the photographer to produce a series of large-format photographs of well-known buildings from around the world.

Sugimoto’s Architecture series (2000-03) consists of blurred images of well-known examples of Modernist architecture across the U.S.

I decided to trace the beginnings of our age via architecture. Pushing my old large-format camera’s focal length out to twice-infinity – with no stops on the bellows rail, the view through the lens was an utter blur – I discovered that superlative architecture survives, however, dissolved, the onslaught of blurred photography. Thus I began erosion-testing architecture for durability, completely melting away many of the buildings in the process.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Later Projects

Sugimoto continues to add images to his early photography series, including Dioramas, Theaters, and Seascapes.

In 2003, Sugimoto started his series titled Joe. The Pulitzer Foundation of the Arts contracted Sugimoto to capture a sculpture by Richard Serra titled Joe.

The series of photographs were developed using silver gelatin on aluminum panels. The Foundation later published the photos in a book that covered the entire series.

The band U2 chose to use Sugimoto’s Boden Sea, Uttwil (1993) for the cover of their 2009 album No Line on the Horizon.

Sugimoto has noted that the agreement with U2 was an artist-to-artist deal, which allows Sugimoto to use the band’s song No Line on the Horizon in any future project in exchange for the image use on the album cover.

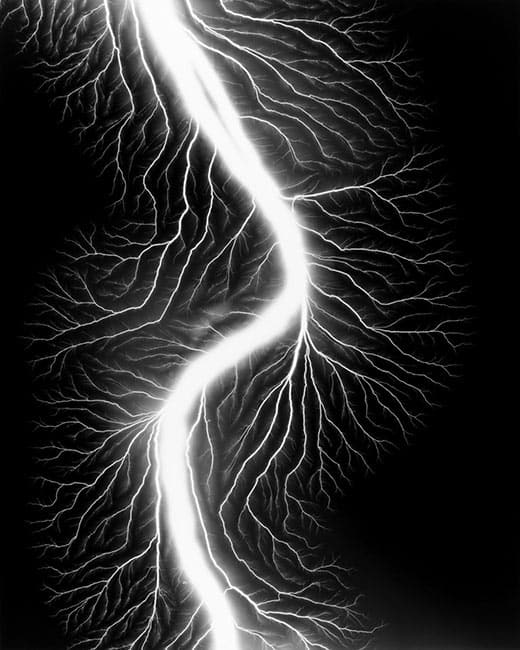

In 2009, Sugimoto began a new series using his extended shutter speed style. The series title Lightning Fields featured slow shutter shots of lightning bolts.

What’s interesting about the series though is that none of the images are actually of lightning captured in nature. For the entire series, Sugimoto used a 400,000-volt generator to create electrical sparks to get his photographs.

Sugimoto’s Style

- Minimalism and simplicity

- Long exposure, capturing time

- Experimental, Surreal

- Conceptual, philosophical

- Repetition, photographic illusion

- Black and White, large format

Influences

Sugimoto has said that he is heavily influenced by Marcel Duchamp – famous for his sculpture of a urinal in the ’50s – as well as the Dadaist and Surrealist movements as a whole.

In the ’70s, Sugimoto was involved with the minimal and conceptual art scenes in New York.

His seascapes series pays tribute to abstract and minimalist predecessors such as Rothko and Reinhardt.

Sugimoto has also expressed a great deal of interest in late 20th century modern architecture.

Related: Snapshot Profile: Michael Kenna

What Camera Does Hiroshi Sugimoto Use?

Sugimoto uses an old wooden large-format camera with 8 x 10 black-and-white film and works in a traditional wet-darkroom to make print enlargements on double-weight gelatin silver paper.

People used to use very big-format cameras. And to me, this method still makes the best quality picture. We think we keep making inventions and tools as sophisticated. This system – it’s very hard to control, but it still makes the best picture. I am sticking to the traditional method.

Other Resources

Recommended Hiroshi Sugimoto Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

Hiroshi Sugimoto Videos

In Conversation: Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Studio Visit

Sugimoto’s Advice for Photographers

In this video (opens in new window) from Louisiana Channel, Sugimoto advises aspiring artists to expose themselves to different jobs and experiences before venturing into the world of art and photography. Great advice for photographers of any age.

Hiroshi Sugimoto Photos

Looking for more Sugimoto photos? Check out his profile at Fraenkel Gallery or visit the Hiroshi Sugimoto website

Fact Check

With each Photographer profile post, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Sugimoto’s work, his life, and how he has had an impact on you (or other photographers) then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Sources

Hiroshi Sugimoto Website, Biography and Artworks

The Blank Screens of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Motion Picture, 1995

Caught in the endless moment, The Telegraph, 2003

Fossilizing with a camera, New York Times, October 2012

Seeing Like A Camera: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Apollo Magazine, February 2015

Studio Visit: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Christies, 2018

A panoramic overview of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Christies, 2019

Hiroshi Sugimoto with Mami Kataoka, 2012

In Conversation: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Getty Museum, 2014

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Theaters, Strand Book Store, 2016

Architecture, Strand Book Store, 2019

Seascapes. Damiani, 2019

Diorama’s, Damiani, 2014