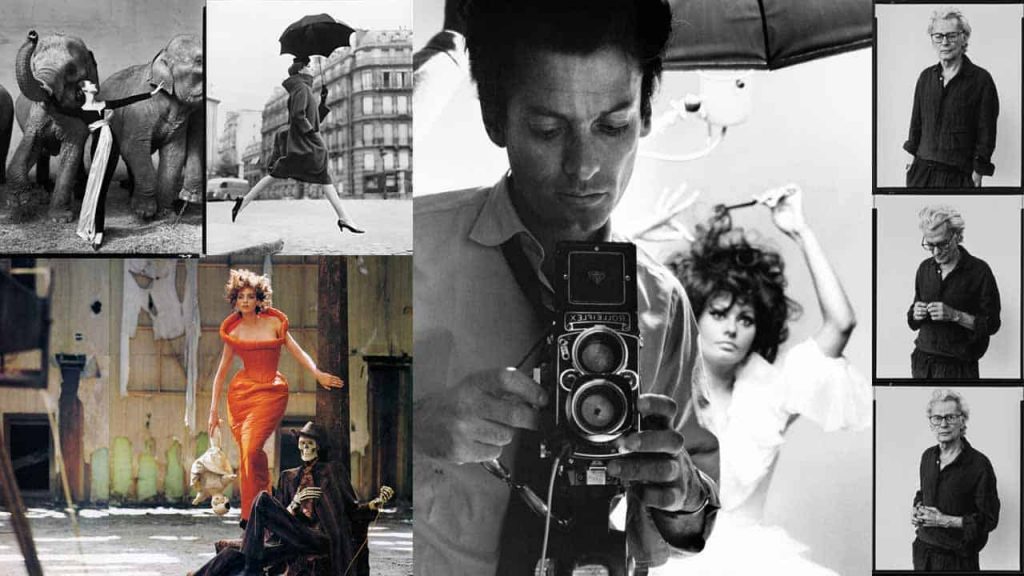

Richard Avedon is considered one of the greatest photographers of all time. In a career spanning 50 years, Avedon revolutionized fashion photography and achieved critical acclaim through his black-and-white character-revealing portraits.

He was known for breaking photographic boundaries in the fashion and political world. Ranging from work found in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar to the New Yorker, Avedon was able to capture the rare emotion and unique essence of his subjects.

If you’re looking for information about Avedon’s photographic style, lighting, philosophy, or even gear, then you’ve come to the right place.

Below you’ll find the most comprehensive and detailed article on the internet about Richard Avedon and his incredible career.

Like all our Profile articles, this is quite a long read (around 25 minutes.) If you don’t have enough time to read the whole article in one go, then bookmark the page and read it a section at a time instead. Alternatively, feel free to skip ahead to whatever section is of interest to you.

If you enjoy the article or you find the information useful, then please share it online through Twitter, Facebook and your own blogs, so other photographers can also learn from the legendary career of one of the greatest photographers of all-time.

Related: The 70 Best Richard Avedon Quotes

Editor Note: This article took 10 days to research and write. Sharing the website or linking back to us takes less than a minute and costs you absolutely nothing. To show your appreciation, we would be extremely grateful if you could share the website through social media or photography forums, or even link back to Photogpedia on your own blog or portfolio website (every link counts). Thank you for your support.

Table of Contents

Richard Avedon Biography

Name: Richard Avedon

Nationality: American

Genre: Fashion, Commercial, Portrait, Documentary

Born: May 15, 1923

Died: October 1, 2004 (81 years old)

Who Is Richard Avedon?

Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and his minimalist portraits.

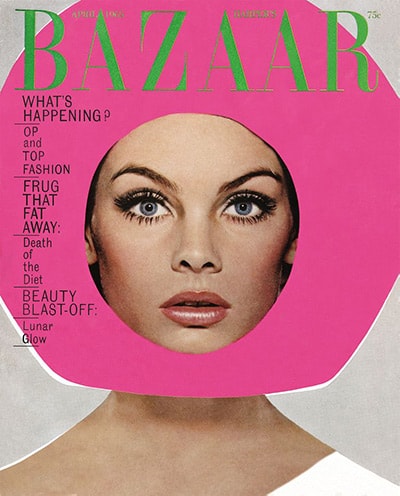

During his career, Avedon worked for fashion magazines, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and served as The New Yorker’s first staff photographer.

He was reputed to be the world’s highest-paid photographer, with his Vogue contract earning him an annual salary of 1 million dollars in 1966 (the equivalent of $8 million in 2020.)

Avedon was such a predominant cultural force that he inspired the classic 1957 film Funny Face, in which Fred Astaire’s character is based on Avedon’s life.

Avedon’s early fashion photography didn’t conform to the conventional photos of the time, whereby models were simply coat-hangers and posed statue-like, almost frozen-in-time. Instead, he enlivened his models, introducing a sense of movement, emotion, and spontaneity into his photos.

In his portraits, his trademark was to present his sitters in full frontal view against a white background. There is no distraction or context in his pictures, other than the features and expression of the face itself.

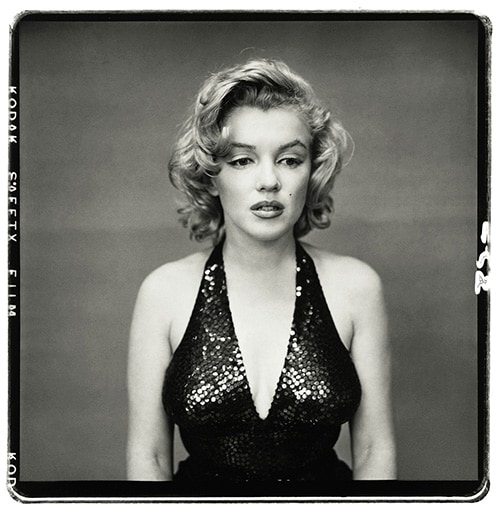

His iconic portraits of celebrities include Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles, Andy Warhol and Elizabeth Taylor.

Avedon’s Influence

His photographic style has been widely imitated by many photographers. Generations of models have been photographed against seamless white backdrops or sat pensively in cafes, whilst pretending to be in love or alone – all because of Avedon.

Throughout his life, Avedon maintained a unique style of portraiture that combined the rigor of the studio with the spontaneity of location work.

Avedon’s incredible body of work wasn’t limited to fashion and portraiture though, with some of his finest images coming from his documentary work on subjects like mental health, civil rights, and the Vietnam War.

The breadth and creativity of Avedon’s work made him one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century.

Richard Avedon is a true genius of photography and one of the greatest artists of our time.

Donatella Versace

As the history of music might be divided into the periods, Before Stravinsky and After Stravinsky, so too can Photography be divided into Before and After Avedon.

Early Life

Born on the 15th of May 1923, in New York City, Richard Avedon, who was also known by family and friends as “Dick,” was the son of Russian-Jewish parents, Jacob and Anna Avedon.

His exposure to fashion and photography began at an early age. Avedon’s father owned a clothing store called, Avedon’s Fifth Avenue and his mother came from a family of dress manufacturers.

The Young Photographer

Inspired by his parents’ clothing businesses, as a boy, Avedon took a great interest in fashion and enjoyed photographing the clothes in his father’s store.

His family subscribed to various women’s fashion magazines, which exposed a young Richard to the exciting breakthrough photography being done by the likes of Martin Munkácsi for Harper’s Bazaar, as well as work by Louise Dahl-Wolfe and Toni Frissell.

Avedon would cut out pictures and then try to imitate them. According to one story, he also covered the walls of his bedroom with magazine fashion photographs.

Equipped with his Kodak Box Brownie camera, he began taking pictures of his younger sister, his mother, and cousin. Louise, his younger sister was his first model. Unfortunately, during her adolescence, Louise struggled with mental health issues; she eventually began psychiatric treatment and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Avedon later described one childhood moment which sparked his interest in fashion photography:

One evening my father and I were walking down Fifth Avenue looking at the store windows. In front of the Plaza Hotel, I saw a bald man with a camera posing a very beautiful woman against a tree. He lifted his head, adjusted her dress a little bit and took some photographs. Later, I saw the picture in Harper’s Bazaar.

Laying the Foundations

Living not far from Fifth Avenue, put him only a stone’s throw from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here he spent hours on end studying female figures, especially those of the ancient Etruscans and others by Modigliani. These later had a profound effect on his fashion photography.

An early infatuation with theatre was inspired by his mother who encouraged his interest in the arts.

When Avedon was ten, he became obsessed with the idea of photographing Sergei Rachmaninoff, who lived in the apartment above his grandparents on Manhattan’s Riverside Drive. After staking out the lobby with his Kodak Box Brownie, he managed to capture the composer standing next to a fire hydrant on West End Avenue.

“I wanted him to see me, to recognize me somehow,” Avedon told a French journalist years later. “I wanted him to give me something of himself that I could keep, something private and permanent that would connect me to him.”

At the age of twelve, he joined the YMHA (Young Men’s Hebrew Association) Camera Club.

During these years, Richard attended New York’s prestigious DeWitt Clinton High School, where he and fellow student James Baldwin put out the school’s literary-art magazine, The Magpie.

The young Avedon wanted to be a poet; his model and inspiration was T. S. Eliot. In 1941, at the end of his senior year and a few days after his eighteenth birthday, he was elected Poet Laureate of the New York City High Schools for his poem, Spring at Coventry.

After leaving high school, Avedon briefly studied poetry and philosophy at Columbia, but he soon took account of his gifts and switched from pen to camera.

The Merchant Marines

When World War II broke out, Avedon tried to enlist in the military, but because of his slight stature and poor eyesight, he was only able to get into the Merchant Marine – a part of the U.S. Navy at the time. His father bought him his first proper camera, a Rolleiflex, as a leaving present.

In the Merchant Marine’s he served as a Photographer’s Mate Second Class, spending most of the war years taking ID photos of sailors at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, and editorial photos for the service magazine, The Helm. It was this experience that in later years greatly affected his portraiture style.

My job was to identify photographs. I must have taken pictures of one hundred thousand faces before it occurred to me, I was becoming a photographer.

Photography Career

After fulfilling his military duties, Avedon returned home with plans to become a professional photographer.

Using some of his photos published in The Helm, Avedon convinced the influential art director for Harper’s Bazaar, Alexey Brodovitch, to let him study photography at his famed Design Laboratory at the New School for Social Research in New York City (where Eve Arnold and Diane Arbus among others, also honed their craft).

During this time, Brodovitch taught him that commercial and editorial work should never be dull or approached in a mundane or tedious manner. Rather, it was the photographer’s responsibility to be creative and bring fresh ideas to photoshoots regardless of the subject matter.

Avedon later revealed that during his time studying under Brodovitch, he never once complimented him on his work.

Brodovich was the father. He was very much like my father. Very withdrawn and disciplined and very strong values. He gave no compliments, which killed a lot of young photographers – they couldn’t take it. I didn’t believe compliments. I never believed compliments even until this day.

Enter Fashion Photography

Avedon started his professional photography career working for the Bonwit Teller department stores. In 1945, with Brodovitch’s help, he joined Harper’s Bazaar as the youngest staff photographer in the magazine history (he was 21 at the time.) The same year, he married model and actress, Doe Nowell.

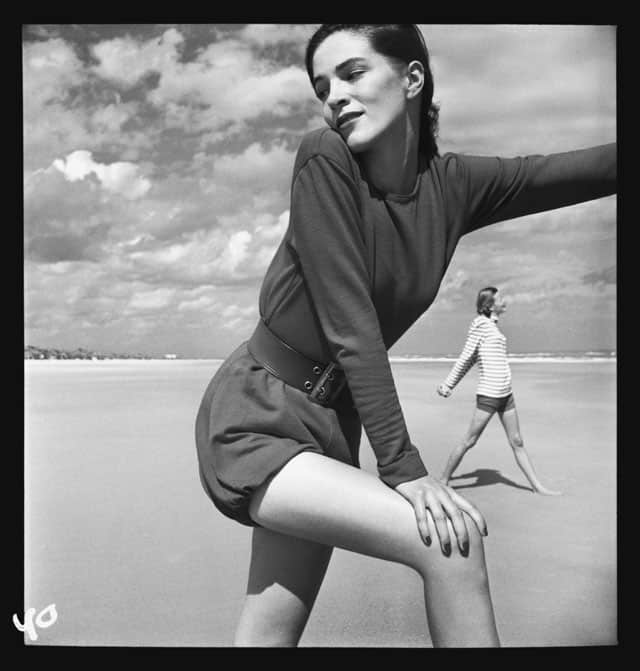

Avedon’s first photos for Harper’s were rejected because Brodovitch thought they were unoriginal and predictable. So, Avedon drove off to a beach with his models and photographed them walking about the sand on stilts and playing leapfrog.

The same year, two of Avedon’s photos were featured in Harper’s Junior Bazaar magazine.

After several years of photographing daily life in New York City, Avedon was assigned by the magazine to cover the spring and Autumn fashion collections in Paris.

Avedon and the Paris Photos

While editor Carmel Snow covered the runway shows, Avedon was tasked with staging photographs of models wearing the latest fashion out on the streets of Paris.

Influenced by the great street photographers of the time, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lisette Model, and Brassai, Avedon added a sense of spontaneity to his fashion photos, something which had never been seen before. His elegant black-and-white photographs showcased the latest fashion in real-life settings.

Women came alive in his photos, and he often captured them: talking to street performers, interacting with people or even sitting in cafés, whilst writing in their journals.

His free-spirited approach revolutionized fashion photography, and he was then given an unparalleled degree of creative freedom.

Avedon would continue to work for Harper’s Bazaar for a twenty-year period, before moving across to Vogue in 1965, where he spent a further twenty-five years.

Life Project

In 1949, Life magazine commissioned Avedon to produce a series of photographs documenting daily life in New York City; an entire issue of the magazine would be devoted to the series for which he received $25,000 advance.

Avedon hit the streets of New York, regarding the assignment as an opportunity to experiment with a different genre.

After taking hundreds of photos for the project, Avedon decided that he couldn’t continue, as he felt he was entering a tradition that was already established by the likes of Helen Levitt, Walker Evans, and Paul Strand; he returned the advance and stored the negatives away for over 40 years.

The trouble was that when I got out into the street, I just couldn’t do it. I didn’t like invading the privacy of perfect strangers. It seemed such an aggressive thing to do. Also, I have to control what I shoot, and I found that I couldn’t control Times Square.

Mature Period

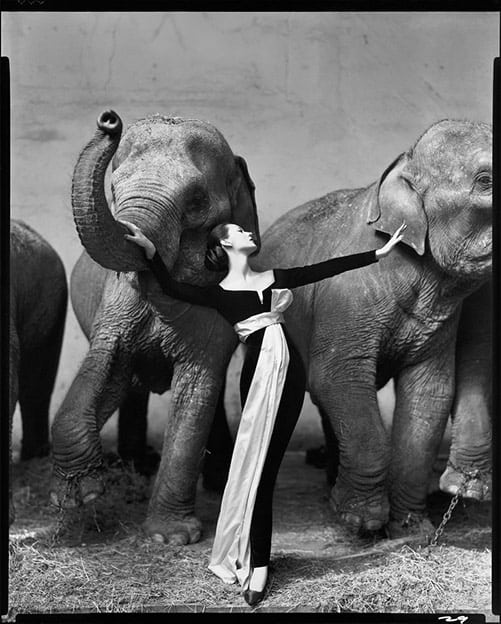

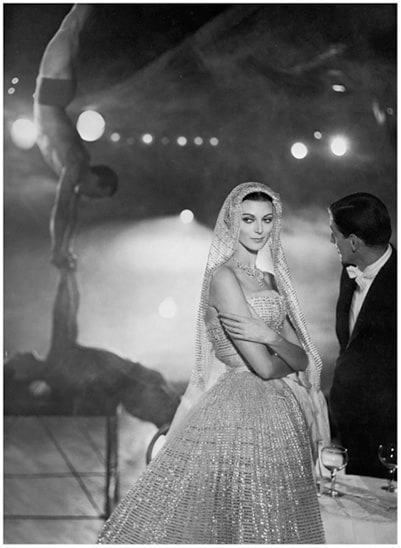

Firmly established as one of the most talented fashion photographers in the business, in 1955 Avedon made photography and fashion history when he staged a photo shoot at a circus.

The most iconic photograph from that shoot, Dovima with Elephants, featured one of the famous models of the time wearing an elegant Dior gown. She is posed between two elephants, with her back arched as she holds on to the trunk of one elephant while reaching out towards the other.

Funny Face

By the ‘50s Avedon was one of the most well-known photographers around. His early career was fictionalized in the 1957 Hollywood musical Funny Face starring Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn.

The film was largely based on Avedon’s first marriage to Doe (which ended in 1949). In the film, Fred Astaire plays a fashion photographer (Avedon) and Audrey Hepburn stars as the model (Doe), he creates and falls in love with. Paramount hired Avedon as a visual consultant for the film and many of his photographs can be seen in the movie.

Also, in 1957, Avedon produced his famous homage to fashion photographer, Martin Munkasci, who created an unforgettable shot of a well-dressed model grasping an umbrella and jumping over a puddle in high heels. Avedon’s recreation features model Carmen Dell’Orefice leaping across a small puddle set against the backdrop of Parisian buildings.

Avedon’s First Book

In 1959, Avedon published his first book, Observations. Well-known writer, Truman Capote wrote the essay and the faces of celebrities and political figures of the time were featured in the pages.

Shortly after the book’s release, Diane Arbus commented, “Everybody who entered Avedon’s studio was some kind of star.” In short, anyone who entered the studio that wasn’t famous already would be by the time they left.

By the early 1960s, Avedon had gone as far as he could go without repeating himself. So, it’s not surprising that his passions shifted from his fashion and commercial work to portraits and reportage.

He developed a strong bond with another art director, Marvin Israel and the work they did together, influenced Avedon’s later career.

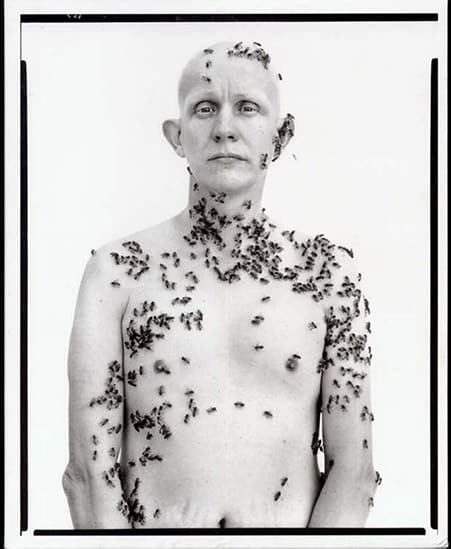

In 1964, Avedon worked with Marvin Israel on his second book, Nothing Personal. The book represented a change in direction for Avedon and was his most adventurous project to date.

His subjects ranged from American soldiers to the Black Panthers and even inpatients residing in a Louisiana State Hospital. The book also featured text from his old high school classmate James Baldwin.

By the mid-1960s, Avedon’s reputation had spread to Madison Avenue, where advertisers ranging from Revlon to Douglas Aircraft booked him for campaigns. He was a man in demand, with his studio annual billings reaching upwards of $250,000.

Moving to Vogue

After guest-editing Harper’s Bazaar’s April 1965 issue, Avedon quit the magazine after he faced criticism over his collaboration with models of color.

Shortly after, he joined Vogue, signing a contract for an unprecedented $1 million. At Vogue, he worked under Diana Vreeland again, after she left Harper’s Bazaar in 1962.

Vreeland gave Avedon free rein and more importantly, she protected him from the interference of Vogue’sart director, Alexander Liberman.

At Vogue, he became the leading photographer and would go on to photograph most of the magazine’s covers from 1973 until late 1988, when Anna Wintour took over from Vreeland as editor-in-chief.

Through the ‘60s and ‘70s, Avedon continued to push the boundaries of fashion photography with often surreal and provocative images. Unlike other photographers of the time, Avedon’s pictures never upstaged the fashion. Instead, he managed to find the right balance.

“With Dick Avedon, you always knew you were looking at a fashion photograph,” said Grace Mirabella, who was editor of Vogue. “He never tried to forsake style for a strong image.”

Creating Memorable Portraits

In addition to his fashion photography, Avedon was also well known for his portraiture.

There’s always been a separation between fashion and what I call my ‘deeper’ work. Fashion is where I make my living. I’m not knocking it. It’s a pleasure to make a living that way. Then there’s the deeper pleasure of doing my portraits. It’s not important what I consider myself to be, but I consider myself to be a portrait photographer.

His black-and-white portraits captured the essential humanity and vulnerability lurking in such larger-than-life figures such as Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin, and Bob Dylan.

In l967, Avedon produced his famous portrait set of The Beatles. The first set became one of the first major rock poster series and consisted of five psychedelic portraits of the group – four solarized individual color portraits and a black-and-white group portrait.

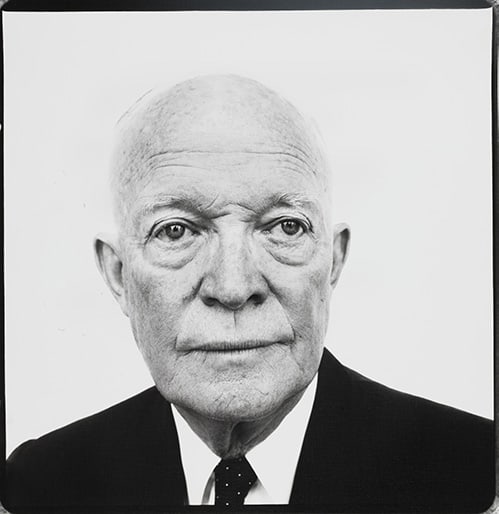

Avedon also took portraits of leading political figures from President Eisenhower to civil rights leaders such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. In addition to his work for Vogue, Avedon was also a driving force behind photography’s emergence as a legitimate art form.

Political and Documentary Work

In 1969, Avedon’s involvement with contemporary politics, particularly the anti-war efforts, inspired him to produce a series of portraits of the Chicago Seven, an anti-war activist group, who were charged with conspiracy and other crimes relating to anti-Vietnam War protests by the Federal government.

In 1971, Avedon traveled to Vietnam as a U.S. war correspondent. The same year, he was arrested for his participation in an anti-war demonstration at the U.S. Capitol building.

Avedon’s father died in 1973, just before his 84th birthday. Avedon had photographed him frequently for six years before his death. Avedon used the photos in a new book and for his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

In 1974, the same year he exhibited portraits of his father, Avedon became dangerously ill. He was diagnosed with pericarditis, an inflammation of the lining of the heart and was hospitalized. Following his release from the hospital, he continued to work.

Later Period

In 1976, for Rolling Stone magazine, he produced The Family, a collective portrait of the American power elite at the time of the country’s bicentennial election.

In the America West

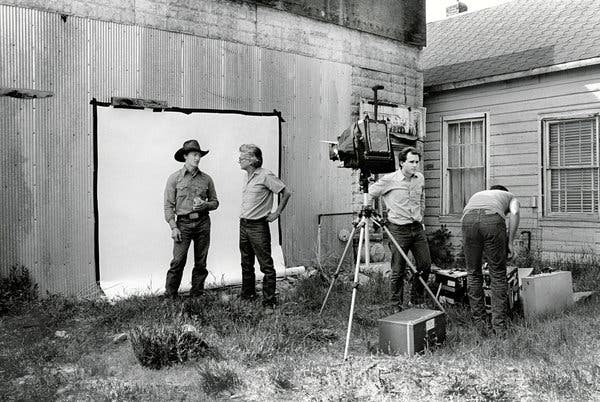

Between 1979 to 1985, he worked extensively on a commission from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, ultimately producing the exhibition and book In the American West.

In the America West marked a turning point in his career. Instead of focusing his lens on public figures and celebrities, he instead photographed everyday working-class subjects such as farmers, housewives, cowboys, and drifters on larger-than-life prints.

Over a period of five years, Avedon traveled throughout the western states. He visited coal mines, oil fields, prisons, state carnivals, fair rodeos and slaughterhouses to find subjects.

For the project, Avedon used a large-format 8×10 view camera, which allowed him to home in on every detail of his subject. Avedon and his crew photographed a total of 762 people and exposed approximately 17,000 sheets of Kodak Tri-X Pan film.

While In the American West is among his most-known works, it has often been criticized for exploiting his subjects and falsifying the west. Avedon was also praised for treating his subjects with the attention and dignity usually reserved for celebrities and political figures. In the documentary Avedon: Darkness and Light, Avedon called the project his best body of work.

Nastassja and the Python

In 1981, Avedon produced another memorable and controversial portrait. The actress, Nastassja Kinski, pregnant at the time, laid on the cold concrete floor of his studio for nearly two hours while an enormous Burmese Python crawled over her body. The Python eventually slithered close enough to stick out its tongue near her ear, giving Avedon the perfect photo. The image was printed in both black-and-white (limited print) and as a full-color poster, which sold over two million copies.

Berlin Wall

Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Avedon traveled to Germany, with the intention of photographing the first German New Year’s party at the Brandenburg Gate since reunification.

Instead of celebration, he encountered violence and unease. The series of photographs documenting the experience was different from his usual pictures: his photos are frenzied, chaotic and feature many close-ups of faces, highlighting that, despite the journalistic overtones, portraiture was still at the heart of Avedon’s work.

Avedon’s interest in fashion photography faded through the years. In 1990 he made the decision to leave Vogue. Now working as a freelance photographer, his work mostly appeared in the French literary and art magazine Egoiste.

The New Yorker

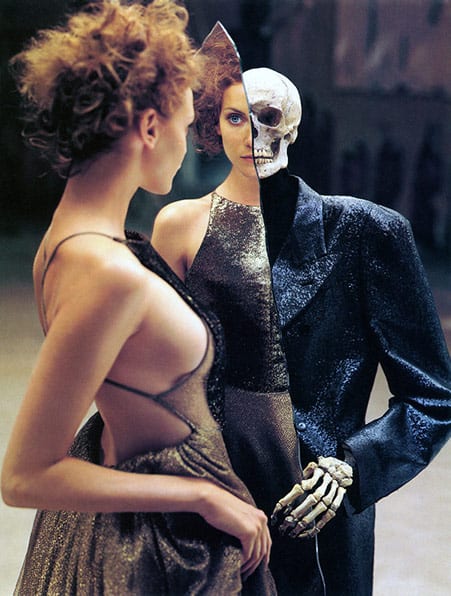

In 1992, Avedon joined The New Yorker as a staff photographer – the first in the magazine’s 67-year history. His famous portraits for The New Yorker include Christopher Reeve, Charlize Theron, and Hillary Clinton. One of his most notable photo stories was his post-apocalyptic, fashion fable In Memory of the Late Mr. and Mrs. Comfort, featuring Nadja Auermann and a skeleton, which was published in 1995.

In the fall of ‘92, he began teaching a series of masterclasses with the support of the International Center for Photography in New York. Additionally, he occasionally produced innovative advertising work for print and television for brands like Calvin Klein, Versace, and Revlon.

Avedon passed away on October 1, 2004, from a cerebral hemorrhage. At the time he was working on assignment for The New Yorker. He was 81 years old.

At the time of his death, Avedon was working on a new project called Democracy. He spent months on the project, shooting politicians, delegates, and citizens from around the country in lead up to the 2004 presidential election.

Legacy

Avedon published eleven books including Observations (1959), Nothing Personal (1964), Portraits (1976), Avedon (1978), In the American West (1985), An Autobiography (1993) and Evidence, 1944-1994 (1994).

Besides his incredible body of work, Avedon left behind a legacy in the Richard Avedon Foundation. The foundation, created by Avedon and maintained by his family, began its work shortly after his death in 2004. Based in New York, the foundation provides a repository for Avedon’s photographs, publications, papers, negatives, and archival materials.

Avedon was also the first fashion photographer to declare himself a serious artist, at the same level as painters. And he did it loudly and very publicly. The statement wasn’t well-received by many people in the art world. But, his belief in his work and self-promotion, resulted in his photos being exhibited at world-class museums. It also opened the door for other photographers to be recognized as true artists.

Avedon married Dorcas Nowell (also known as Doe Avedon) in 1944, and they remained married for six years before parting ways in 1950. In 1951, he married Evelyn Franklin; they had one son, John, before separating.

Recognition and Awards

In his lifetime, Avedon received countless awards and honorary degrees. There are too many to list, so here are just a few of them:

- 1985: American Society of Magazine Photographers’ Photographer of the Year

- 1989: Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America

- 1989: Honorary graduate degree from the Royal College of Art

- 1993: Master of Photography Award from the International Center of Photography

- 2000: Lifetime Achievement Award from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

- 2001: Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 2003: National Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 2003: The Royal Photographic Society’s Special 150th Anniversary Medal and Honorary Fellowship (HonFRPS)

Since the 1970s Avedon’s work (both his fashion photography and portraits) has been exhibited in the United States and across the world. His most notable exhibitions were his first retrospective at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1970 and his final major retrospective held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in late 2002.

Photography Style

In his long career, Richard Avedon has produced every genre of photography, from his advertising work for clients such as Revlon and Hertz to fashion spreads for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue to documentary projects such as Nothing Personal and In the America West. Then, of course, you have his remarkable portraits of some of the biggest icons of the 20th century.

Avedon never believed that the camera offered an undeniable truth. This is a painful realization for many photographers and one that is still resisted even today. Whether this came to Avedon instinctively or through experience, we’ll never know.

But he did realize that the notion of truth was irrelevant quite early on in his career, which gave him real freedom with his photographs. He could approach photography as the making of pictures and not the taking of pictures.

For Avedon, every picture, whether a fashion fantasy or a portrait of an old woman became in a way theatre. His way of telling a story through a visual image.

That said, when it comes to trying to define Richard Avedon’s style of photography, it’s impossible to do his photographic genius justice in a few paragraphs. Instead, look at his body of work and then decide for yourself.

One thing is for certain: Avedon took the kind of pictures that got people talking.

To be an artist, to be a photographer, you have to nurture the things that most people discard.

Fashion Photography

While his studio shoots avoided anything but the plain white background, his early fashion photography used a range of diverse locations, from circuses and zoos to the streets of Paris to the launching pads at Cape Canaveral.

Avedon’s early fashion photographs were characterized by movement and action. He didn’t conform to standard techniques of studio photography, where models stood emotionless and seemingly indifferent to the camera. Instead, he showed models smiling, laughing and even jumping about which was revolutionary for the time.

One of the most powerful parts of movement is that it is a constant surprise. You don’t know what the fabric is going to do, what the hair is going to do, you can control it to a certain degree – and there is a surprise. And you realize when I photograph movement, I have to anticipate that by the time it has happened – otherwise it’s too late to photograph it. So, there’s this terrific interchange between the moving figure and myself that is like dancing.

Avedon always took special care to show every detail of the clothing while still introducing blur and other creative effects in his photos.

I began trying to create an out-of-focus world – a heightened reality better than real, that suggests, rather than tells you.

Avedon – The Storyteller

Avedon’s fashion photographs also introduced some form of narrative, which was a departure from the static, posed and formal fashion photography more prevalent at that time.

His fashion photos are a perfect example of how to tell a story in a single frame. His models came alive in his photos and many of the stories often revolved around the high life or the elegance of being a woman.

By using a simple narrative, he believed that viewers and consumers would invest as much in a story about a dress (and the model) than the dress itself. Avedon knew quite early on, that you don’t sell the fashion, you sell the experience of owning the fashion.

His leading lady must always be involved in a drama of some sort, and if fate fails to provide a real one, Avedon thinks one up. He often creates in his mind an entire scenario suggested by a model’s appearance. She may be a waif lost in a big and sinful city, or a titled lady pursued in Hispano-Suizas by gentlemen flourishing emeralds, or an inconsolably bored woman of the world whose heart can no longer be touched – and so on. Avedon models play scene after scene from these scripts, and sometimes helps out by actually living an extra scene or two. The result is extraordinary for its realism – not the kind of realism found in most photography but the kind found in the theatre.

Winthrop Sargeant, The New Yorker, 1958

The Art of the Story

For his innovative fashion photographs, you’ll see examples of his approach in Funny Face watching photographer Dick Avery (Fred Astaire) shooting pictures of Jo Stockton (Audrey Hepburn) in various locations around Paris. Like Avery, he would also give his models a simple storyline to follow.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Avedon became dissatisfied with daylight photography and location shoots and turned to studio photography for most of his fashion work, using strobe lighting which was still quite new at the time.

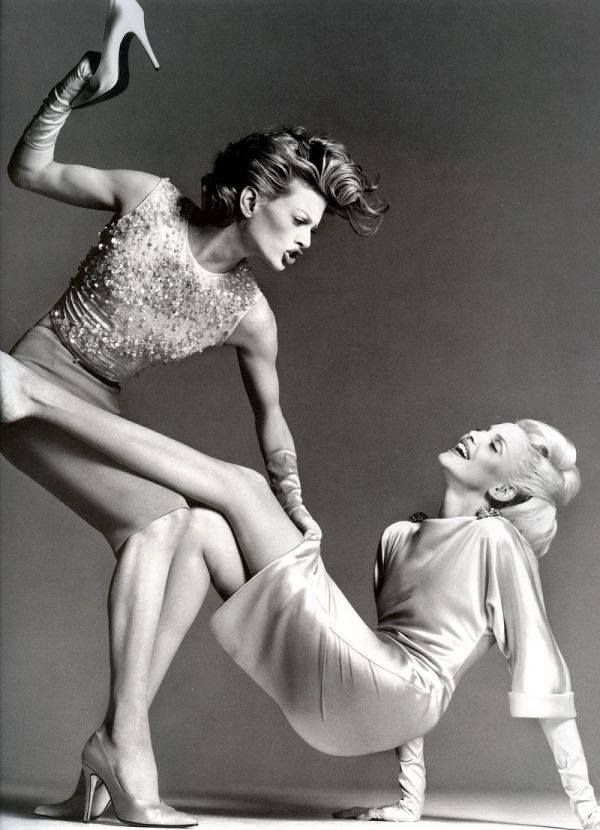

Dick would give them a story. When Kristen [McMenamy] and Nadja [Auermann] came out in two little black suits, he was like, ‘Oh, I think you’re crows, and you are on a branch. There’s a worm on the floor and you’re fighting for that worm.’ Very simplistic, childlike scenarios that were very immediate.

Tim Walker, Photographer and former assistant to Avedon

You can see how this photoshoot played out: in one image, McMenamy threatens Auermann with a spike-heeled shoe; in another, Auermann throws a punch while McMenamy laughs at her.

Preparation

The shots might seem improvised, but his photoshoots are far from spontaneous. Avedon would put a lot of time into preparation: researching locations, sketching proposed shots and taking test photos. On the day, Avedon would talk to the models before he would begin; discussing what characters he wanted them to portray and poses he had in mind, as well as telling them the stories he wanted them to act out.

Dick was the most brilliant of all the flashes that illuminated my professional path. His impatience was an inspiration in itself. The preparation he made for each sitting, the perfectionism – sharp, like a scalpel. And then the way he directed. His personality, which helped him clinch every shot. His timing. This man created the modern woman – the Avedon Woman.

Hiro, Photographer and former assistant to Avedon

Working with Models

Avedon’s own interest was always in the people, never in the fashions. In fact, the fashion tended to add a layer of complication to what he fundamentally believed was the relationship between the photographer and the model.

All his early models were typically brunettes with high cheekbones in memory of his younger sister Louise, who died at the age of 42 in a mental institute.

All my first models, Dorian Leigh, Elise Daniels, Carmen, Marella Agnelli, Audrey Hepburn, were brunettes and had fine noses, long throats, oval faces. They were all memories of my sister. My sense of what was beautiful was established very early through the way in which I experienced her. I photographed her from 14 to 18. She was the prototype of what I considered beautiful in my early years as a photographer.

Music always played an important role in Avedon’s studio. To inspire his models, he would often play music and sometimes dance along with them. As Avedon stood behind his Rolleiflex mounted on a tripod, Frank Sinatra or even the Kinks would blare out from the record player nearby.

Since he began photographing models in the mid-1940s, Avedon would always make the effort to ask them what music and food they preferred. This contributed to the relaxed atmosphere of the studio. As Polly Mellen, a Vogue editor once remarked, “They all wanted to please him.”

Avedon and the Cover Shoot

Avedon was one of the most prolific fashion photographers of all-time. Between 1952 and 1956, he produced a remarkable 26 covers (a cover every other month) for Harper’s Bazaar. The only other photographer who rivaled his record was Louise-Dahl Wolfe who worked for Harper’s from 1936 through to 1958.

He was equally productive inside the magazine, having several pages devoted to his fashion and portrait photography in practically every issue.

Unlike other photographers, Avedon wouldn’t give in to the demands of his clients. Even though he would take hundreds of exposures on a job, he would only let editors and art directors see the few that he chose for them. The only exception was when working with Diana Vreeland.

Commercial Work

Although Avedon was already famous for his fashion photography, it was his commercial advertising work that paid the bills and made his documentary work possible.

Some photographers go to the foundations and beg to hold an exhibition or go off and marry rich women. Or worse yet, they become martyrs with a following. This is because they don’t know how to make money. I don’t beg foundations or the government for money. I earn my living working with magazines and by doing advertising campaigns.

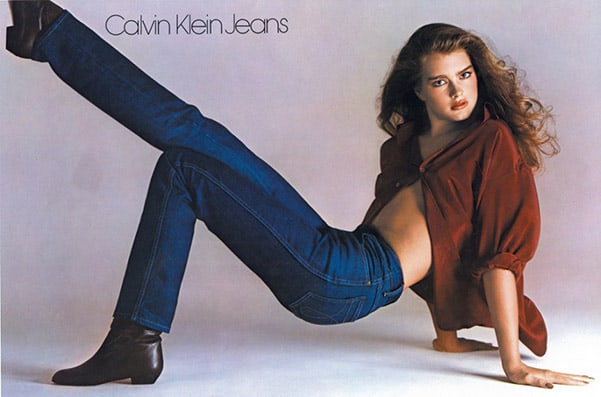

Avedon did commercial work throughout his career and lensed campaigns for the likes of Revlon, Versace, Hertz and Calvin Klein (including the controversial ads featuring Brooke Shields.) Avedon was a smart businessman who embraced advertising work, putting as much care into it as he did for the more creative jobs.

But even a creative master like Richard Avedon would still be presented with an approved concept and storyboards from clients. Avedon would shoot to the client’s specification, and then shoot his own interpretation of the concept, in hope that they would find his own ideas better.

Commercial Work and Fine Art

Many of Avedon’s most famous photographs, were shot for commercial purposes. Ironically, these photos tend to be more highly regarded by collectors than photos Avedon did with the intention of creating images as fine art. Many of his commercial photos have since been regarded as fine art and exhibited in museums and sold in photo galleries.

This is no different from the great artists in history. Before the “art market” was invented in the mid-1800s, what we now call art was produced by craftsmen for commercial purposes, usually on commission from a government, the church or wealthy patrons. This was art for a practical purpose, not for art’s sake. That is the definition of “commercial.”

So, it is significant that so much of accepted photographic art, including that of Richard Avedon, was done so often with the intention of things like selling products, copies of magazines, promoting travel, publicity, and other commercial purposes.

Portraits

Avedon was foremost a portrait photographer and over his career, he photographed countless icons such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, the Beatles, and President Eisenhower.

His portraits are easily recognized by their minimalist style, where the person is photographed looking squarely in the camera, posed in front of a plain white background, typically in black and white.

A photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows [they’re] being photographed, and what he does with this knowledge is as much a part of the photograph as what he’s wearing or how he looks.

The Storywriters Truth

Avedon was only interested in how his portraits could capture the personality and soul of the subject. He would at times evoke reactions from them by guiding them into uncomfortable areas of discussion or asking them psychologically probing questions.

For example, if he was trying to make a sitter feel uncomfortable, he wouldn’t say anything to them. He would purposely heighten their level of discomfort to get the range of emotion he was looking for.

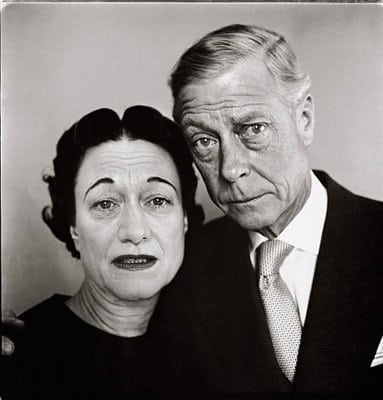

The Windsor’s

Take the Duke and Duchess of Windsor as an example.

The couple were experts at portraying marriage bliss and serene old age for the camera. Avedon wanted to produce something different. He arrived very late for the sitting, sending his assistant ahead to set up the equipment. When he arrived, he found himself at an uncharacteristic loss to unsettle their camera-ready faces. Knowing how much they loved their dogs, he apologized for being late and told them that his cab had run over a little dog on Park Avenue.

As they listened to the sad story, the dog-loving Windsor’s looked sympathetically at a flustered Avedon. As he continued his story, he pretended to adjust his camera, while unobtrusively snapping frames and capturing the unguarded moment. After a while, he told them he was ready to begin and the Windsor’s composed themselves in their customary serene formal manner. Avedon already had the photo he wanted.

When the photos appeared, everyone commented on how wonderfully Avedon had captured the Duke’s grief and suffering at having been forced to abdicate the throne for the woman he loved.

Through these means, he would produce images revealing aspects of his subjects’ character and personality that were not captured by others. He’d wait for what is called the “story-writers truth,” the moment in which people are naturally themselves.

A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.

Connection with Subject

Annie Leibovitz wrote in her book Annie Leibovitz at Work, that Avedon “seduced his subjects with conversation. He had a Rolleiflex that he would look down at and then up from. It was never in front of his face but next to him while he talked.”

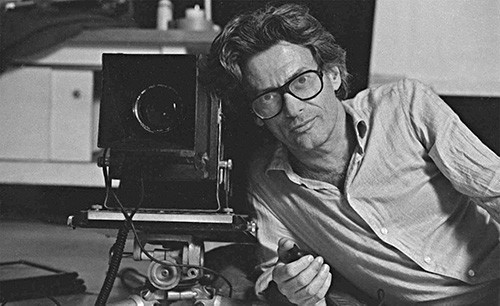

Avedon used a square-format Rolleiflex for nearly all his fashion and portrait work up until the late sixties. In the latter part of the decade, his way of working had grown both too easy and too disconcerting and he decided to change his approach.

The camera was almost taking the pictures itself. Hovering over the camera and peering into it, I never saw the people who were there, or saw them seeing me.

For Avedon, his portraiture was about that authentic connection with the sitter.

In 1969, he began using an eight-by-ten-inch Deardorff view camera on a tripod – a cumbersome setup that brought with it a new method of working and a new set of constraints.

Using the Deardorff, Avedon posed his subjects against a white seamless backdrop, illuminated by shadowless, diffused sunlight or flat studio lighting. With the unessential stripped away, what remained was the relationship between the photographer and the subject.

For Avedon, who always worked not behind, but to one side of, the camera, the camera became a silent witness to the face-off between the two people making the photo.

I’ve worked out of a series of no’s. No to exquisite light, no to apparent compositions, no to the seduction of poses or narrative. And all these no’s force me to the ‘yes.’ I have a white background. I have the person I’m interested in and the thing that happens between us.

The Self-Portrait

Avedon himself has described that quality as “the unresolved mystery between reporting and storytelling.” Avedon has never disguised the fact that his own response is more important to the finished image than the feelings of the person he photographs, that his portraits are less a “portrait of them than… a portrait of what I think about them.”

With his portraits, Avedon, in a way, was really looking at himself, trying to find the darkness and light of his own existence. He would always remain in control of the sitting – they are his pictures, not the subjects.

For the In the America West project, Avedon would stand next to his 8×10 camera and gaze at his subject. Very few words were exchanged between the photographer and his subject. Avedon would shift his weight, change his posture or body language. The subject, not knowing what else to do would do the same. He wouldn’t hide behind the camera; the photoshoot became a collaborative dance. That’s the brilliance of Avedon’s portraits. And it wasn’t a case of just mirroring either.

Avedon’s presence and quiet communication was at the same time a statement, a question, and an invitation – I’m with you, trust me and follow my lead. And the subjects almost always did.

Photographing the Surface

Unlike other photographers of the stars, Avedon’s portraits were not always flattering and at times, they were downright brutal.

Avedon considered it his responsibility as an artist, to portray the subject, how he saw them in the moment, and he couldn’t care less whether it’s how they see themselves or how other people see them. Avedon took whatever was given to him by his subjects and made it his own.

To say it in the toughest way possible, and the most unpleasant way, what right do Cézanne’s apples have to tell Cézanne how to paint them?

Richard Avedon, Public lecture, Boston in 1987

Coco Chanel never forgave him for exposing her aging neck in 1958. But aside from her neck, he also revealed and celebrated her formidable determination and her will to stay glamorous. No one else could have made the portrait-like Avedon did and anyone who sees it is unlikely to ever forget it.

Remaining Truthful

Avedon always remained true to photography. Sacrificing flattery to create portraits that trust nothing but the surface. And if the surface is old and wrinkled, or young and empty, or bewildered and lost in the face of death, then so be it.

My photographs don’t go below the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues.

Now, if you’re a studio photographer or even an amateur photographer shooting your family or friends, Avedon’s method may not make you very popular. Then again, it depends on whether you want to be someone who just takes sophisticated passport photos or someone who makes art. The saying is, “an artist gets paid for their vision, not to record.”

Avedon believed portraits were meaningless unless they had a story to tell or at least a truth to communicate. “Faces,” he once said, “are the ledgers of our experience”.

Influences

Avedon’s early photography influence was Martin Munkacsi, whose fashion photos for Vogue in the 1930s featured outdoor locations such as the beach, where models dipped into the surf and strode along the shore wearing the fashion of the time.

Another influence was Jacques-Henri Lartigue, whose images at the turn-of-the-20th-century, showed women together at the park or cafe, always caught up in their own world.

Then there’s Edward Steichen. Steichen’s later work for Vogue and Vanity Fair and particularly his celebrity portraits have the same quality as Avedon’s. In both cases, the photographers seemed intent on catching their subjects lost in a moment of time.

Away from photography, Avedon’s fondness for realism and delving into the souls of his sitters was something he acquired from his favorite writers like Elliot, Proust, Beckett, and Chekhov.

Then you have the world of art, in particular Goya, whose unflinching honesty Avedon found incomparable and deeply compelling. When he wasn’t working, he went to the theatre and ballet, as well as museums and art galleries.

What Camera Did Richard Avedon Use?

Avedon’s photography genius had little to do with his choice of cameras; instead, it centered around his ability to manipulate subjects into revealing their true personalities in the case of portraiture, and his sense of storytelling and fantasy in the case of his fashion photographs.

If it was possible, he would have preferred to download images directly from his eyes and skip the whole photographic process. In fact, in various interviews, he always maintained that the cameras just got in the way.

I hate cameras. They interfere, they’re always in the way. I wish: if I could work with my eyes alone.

Most of his work was done with two film formats: Medium format (2 ¼ Square) and 8 x 10.

The mobility of medium format (Rolleiflex) would lend itself to Avedon’s fashion photography. Working with the Rollei gave him the mobility needed to keep pace with actively moving models, as well as a negative bigger than 35mm for higher quality and the ability to easily create larger prints.

When he wanted a tighter shot (head or head and shoulders, then he would slip a close-up dioptre on the Rollei or switch to the Hasselblad 500cm with a longer 150mm F/4 lens.

Portraits were more or less the domain of his 8×10 cameras, although he alternated between formats freely, depending on how fast he needed to work. As you can imagine the 8×10 format would slow him down. In the studio, he would use his 8×10 Sinar Norma and out in the field a collapsible 8×10 Deardoff wooden field camera would fill in for the Sinar.

List of Cameras and Lenses

Here’s a complete list of the cameras that Avedon used for his work:

2.8 Rolleiflex

Avedon never used built-in exposure meters. Some of his Rolleiflex cameras had Zeiss Planar lenses, others had Schneider Xenotars. The actual lens didn’t matter, as long as it was an f/2.8 and 80mm for just the right perspective. He frequently used closeup lenses, in which case the top one had some correction for parallax.

8”x 10” Deardorff

This wooden field view camera was relatively light in weight and folded up compactly. It was at first equipped with a 12” lens, probably a Goerz-Dagor in an Ilex shutter, but this was later replaced with better optics.

8”x10” Sinar Norma

In 1963, Avedon purchased the more advanced Sinar Norma modular monorail camera to speed up his photography and primarily for studio use. It was equipped with a 300mm f/5.6 Schneider Symmar lens and a Sinar automatic shutter and was mounted on a sturdy Gitzo tripod.

He also used a Schneider Wymmar-S 360mm f/6.8 lens and a Fujinon 360mm f/6.3 lens with both the Deardorff and Sinar Norma.

Hasselblad 500cm

Avedon started to use a Hasselblad with the 150mm f/4 lens in the early sixties for tighter shots out on location. Around 2002, he started experimenting with phase one digital backs for his advertising and commercial work.

Mamiyaflex

Although not as rugged as the Rolleiflex, the twin-lens Mamiya had certain advantages for closeup headshots as it focused much closer. It had a clumsy but very effective method of parallax control and allowed the use of longer lenses.

He probably didn’t much care for it but used it for cosmetic and hairstyle photos where a Rollei with its 80mm lens would have introduced too much distortion. In later years, he used a Hasselblad for these photos instead.

Asahi Pentax 35mm SLR

Avedon very rarely worked with 35mm other than for personal snapshots, but he did use a Pentax for “paparazzi” shots during the 1962 Paris collections, and for the opening and closing photos of his 1964 book, Nothing Personal.

The above cameras are the only ones that have been mentioned in articles, documentaries, and books. He did own a Leica M3 but never used it.

Focal Lengths used by Avedon

For reference, the Rolleiflex’ 80mm lens and the 360mm lenses for the 8×10” cameras are roughly 50mm equivalents on 35mm format. The Hasselblad 150mm is the equivalent of around 85mm.

So, there you have it, Avedon created some of the greatest photos of all time with effectively just two focal lengths: 50mm and 85mm.

If you ever get the chance, then I recommend purchasing the American Photo March/April 1994 issue, as this gives a great insight into Avedon’s cameras and studio setup.

Which Film Did Avedon Use?

Avedon’s choice of film was just as basic as his camera gear. For his medium format work, he used Kodak Plus X (rated at El 80), although he also used Kodak Tri-X, the amateur (ISO 400) version, because it pushed better. Professional Tri-X (rated at El 200) was used for his large-format photography in any light.

Film would be developed using Kodak D76 or HC-110 or Harvey’s Panthermic 777 (no longer available).

For color work, all I could find out was that he used Ektachrome E-3 film for the In the America West project. If anyone knows anything else then send me an email, so I can update the page.

Avedon’s negatives were dense, due in part to his disregard for recommended development times. Even with normal exposure Tri-X might get 15 minutes in the tank with D-76 – over half again, the usual amount.

Avedon used the Norwood Director meter to check his exposures. The meter measured incident rather than reflected light and was the standard for Hollywood cinematographers for many years.

Avedon’s Printing Technique

Avedon’s busy schedule didn’t afford him the luxury of printing his own work. While others may have got their hands wet on his behalf, he did oversee every step of the process.

With his printers, he always gave them verbal clues on what he wanted, specifically the emotionally quality of the print. He’d talk about making a print happy, angry, fiery, romantic or kind.

Once the printer had the brief and understood what he was looking for, he would then leave it up to them to realize that. If he was unhappy with the first test prints, the print would be made over again.

Once satisfied with the test prints, he would then begin mixing and matching the different parts of the prints.

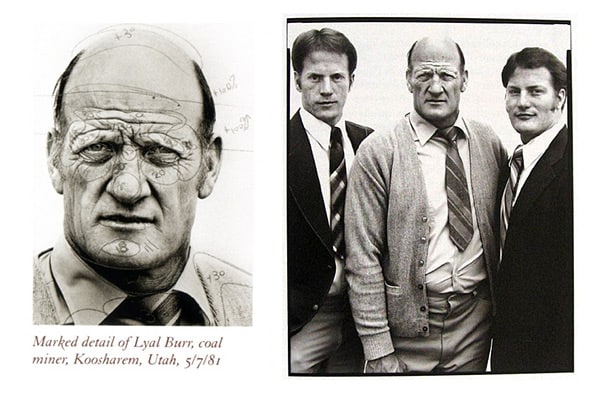

For example, with a portrait, he would choose the one with the best eyes and if the overall print wasn’t good enough for him, he’d cut out a nose or a mouth from another and paste it on.

For a location shoot, he might cut out a head from one print and put it on the body of another, he would then cut out part of a building that had the right lightness and put it on another that was darker.

The Final Print

An Avedon final print is normally a composite of all the test prints made up to form the perfect print. Never the first prints made.

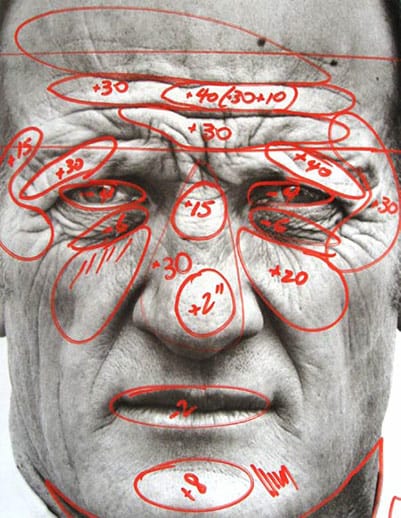

If Avedon still wasn’t satisfied, even after all the changes, he would grab a grease pencil and start marking it up all over again. Creating the perfect print was always a process for him.

There’s a famous instructions image, which was published in Avedon’s book, Evidence, which shows all the dodging and burning that went into making the final printed image. These instructions were not made by Avedon, but by his principal printer at the time.

The purpose of the image is to ensure that prints made for collectors are identical to others exhibited in major art museums around the world.

The numbers on them represent specific “dodging” and “burning-in” times in seconds for each section of the image. Anyone experienced in darkroom printing will understand how difficult they are to follow.

Printing for In the America West

This black and white version of printing instructions is from Avedon at Work: In the American West by Laura Wilson. Laura has a dedicated section on the printing process used for the In the American West exhibition. If you want to know more about how Avedon shot the project and his photography process, then this is the book to get.

The difficult and time-consuming process ok making these prints began in the basement darkroom of the Avedon studio in New York. Ruedi and David [Liittscwager] started with a set of 16-by-20-inch prints. Dick rejected them all. He felt that the tone was heavy; they were too black and had too much contrast. In reprinting, Dick’s directions were rarely technical. He would say simply, “Make the person more gentle,” or “Give the face more tension” This unconventional advice forced Ruedi and David to try to Understand the emotional content that Dick sought in each portrait. On test prints, Ruedi recorded the necessary manipulations with a red grease pencil. The exposure times, plus or minus, were in seconds to indicate where to darken or lighten an eyelid, or a nose, or the wrinkle on a forehead.

Excerpt from the Avedon at Work: In the America West (p. 114-117)

Laura Wilson – Avedon’s former assistant for six years

Getting the Perfect Print

Richard Avedon wasn’t a purist in the traditional sense. He wouldn’t hesitate to crop or manipulate the image in some way to get the perfect print in the darkroom.

Perhaps the most important factors when it came to making prints were time and money. No expense was spared, and it could often take as long as a week to print one image. Prints were made repeatedly until the perfect one finally emerged.

Avedon’s Lighting

The secret of Avedon’s studio lighting should not come as a surprise to anyone familiar with his energetic style of fashion photography.

Below, I’ll try and explain his lighting, or what he liked to call his “beauty light” in more detail.

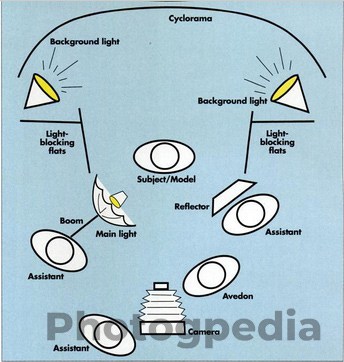

Instead of mounting his main source light on a stand – the usual practice, and one that limits movement – he would get an assistant to hold a boom pole with the light mounted on the end.

Once Avedon’s had the light setup to his liking and the strobe reading was taken, the assistant would then follow the model with the light, the same way a sound technician on a movie set would track actors with a boom microphone.

As Avedon would shoot, the assistant would move with the model. For consistent exposures, the assistant would need to keep the light at the right distance from the subject. The light was always kept very close to the subject, just outside the camera’s field of view.

By using this approach, there was a calculated margin for error. Avedon liked the subtle and unexpected changes that could happen through working this way.

Avedon’s moving light was normally bounced into an umbrella or small dome to soften it, while two other assistants would angle 12” squares of metalized cupboard to reflect light into the subject’s eyes. Adjustable flats were placed either side of the subject to stop unwanted light from filling in shadows or causing flare.

When describing the process, Avedon would often compare it to a Japanese ballet, where everyone knew their roles and did it silently and with great agility and finesse.

When working in color or shooting 8×10 format, where the film can be less forgiving Avedon would have his key light in a fixed position.

White Background

Richard Avedon is arguably the most influential “white background” photographer of all time. By shooting against a white background, Avedon eliminated all distractions, putting the focus on the subject.

His white background would be lighted by two strobes heads on adjustable poles. If Avedon wanted a grey background, he would power down the lights so they were two stops less bright than the main source light (if a typical meter reading for the subject is F8, then for grey you would need to set the lights to F4.) If Avedon wanted a white background, the lights are instead powered up to within half a stop of the main light to insure a hint of tone.

In the America West Lighting

When Avedon did In the America West project, he would shoot his subjects outside against a white seamless paper which was gaffer-taped to the shade side of whatever structures he could find (barns, motorhomes, etc.) “I wanted the thrill of the person to come forward out of the white,” Avedon said

Avedon photographed his subjects in the shade, using available light and avoiding the harsh shadows and highlights of sunshine that dominate a face. He didn’t use any strobe lights because he felt they gave the photographs an artificial look. He wanted the special beauty of shaded light which had more of a neutral quality to it.

How Do You Get the Avedon Look?

I think there’s one thing that Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn and Diane Arbus all have, and something I share, is the complete obsession with work and work every day. If you do the work every single day, hopefully the work gets better.

Charlie Rose Interview, 1993

Many imitators have struggled to replicate his signature style. Getting what is known as “The Avedon Look” isn’t a case of shooting against a white background with a large-format camera (or Rolleiflex) loaded with Kodak Tri-X.

Avedon often said that there is an element of himself in every photo he has ever taken. Now unless you’re born Richard Avedon, getting an Avedon photograph is going to be impossible. What we can hopefully do though is give you a few hints to help get close enough to his signature style.

Richard Avedon taught me that if you go into a photo session and come out with what you had hoped for, it’s a failure. You need to be surprised if you want it to be magical.

Amy Arbus, Photographer and former Avedon Masterclass member

Capturing the Moment

Avedon always knew what he wanted before going into his photoshoot. However, instead of getting stuck on getting the photo he planned, he would remain flexible and photograph what was in front of him instead. If you look at his most iconic photos, you’ll notice that they’re photos that can never be recreated. His Nastassja Kinski, Charlie Chaplin, and Marilyn Monroe portraits are perfect examples of this.

Nothing I have ever done has been calculated. It comes out of instinct.

Avedon also liked to be able to shoot models being active and in motion whenever possible. When photographing subjects, he would tell them to jump, and to “jump higher!” at the same time he would be jumping with them.

Snapshots that have been taken of me working show something I was not aware of at all, that over and over again I’m holding my own body or my own hands exactly like the person I’m photographing. I never knew I did that, and obviously what I’m doing is trying to feel, actually physically feel, the way he or she feels at the moment I’m photographing them in order to deepen the sense of connection.

What’s often overlooked in Avedon’s style, is the trust and connection he builds with the subject. Avedon would often stand in the same position as his subjects on a photoshoot, by mirroring the subject’s body language he was able to build a rapport quicker.

It’s something I do unconsciously, I want to know how it feels. I think I want to encourage the thing I like about the way he stands. I want to encourage without words.

American Photo: Avedon, March-April 1994

The Visual Author

Avedon was incredibly versatile, and his method of shooting would change depending on what assignment or project he was shooting at the time. He wouldn’t approach an advertising job the same way as his portraiture, nor his documentary work the same as his fashion photos.

He was also fearless, and nothing would stop him from making his photographs and doing whatever it would take to fulfill his vision.

So, getting “The Avedon Look” isn’t a case of simply following a formula. First, you’ve got to decide what genre of his photography you’re trying to replicate and then study his work in more detail. If you’ve made it this far in the article, then you’ve probably picked up quite a few hints and tips that will help you out.

I’m just a born photographer and I get bored. When I get bored, I move to the next place, the one thing about the life that’s fallen on me is that I can when I’ve done too much fashion, stop. When I’ve too much of the deeper more intense and painful part of myself, I can go back to another place. It’s like being a writer who writes on many subjects.

Richard Avedon the Charlie Rose Show (1997)

Other Richard Avedon Resources

Recommended Richard Avedon Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases. All links to Amazon are affiliate links, which means we receive a small commission for any purchases you make. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but this commission keeps Photogpedia running and is the reason we’re able to offer so much free content.

To learn more, read our Affiliate Disclosure page. Thank you for your support.

- Richard Avedon: Photographs 1946-2004

- Avedon: Evidence: 1944-1994

- Avedon: Fashion 1944-2000

- In the American West, 1979-84

- Avedon at Work: In the American West

- Avedon: Something Personal

Videos of Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light (1996)

This must-see documentary film provides a fascinating portrait of Richard Avedon and his incredible body of work.

Not only will you learn how Avedon made his most iconic photos, but you also get to watch the master photographer at work on his fashion and portraits shoots.

Among the documentaries many highlights are Avedon’s recollection of Marilyn Monroe dancing in his studio for hours so that he could capture a never-seen-before side of her persona. Another segment, Avedon describes how Charlie Chaplin called him out of the blue and visited him for a portrait session days before leaving the U.S.

Darkness and Light is a documentary produced by PBS as part of the American Masters Series in 1996. If you have 90 minutes to spare, then I cannot recommend this documentary enough.

Charlie Rose: Richard Avedon (1993)

In this 60-minute interview from May 1993, Richard Avedon talks to the chat show host, Charlie Rose about life behind the lens, photographing public figures and his book, An Auto-biography Richard Avedon. You can learn a lot by listening to Avedon discussing his photography philosophy, most iconic photos and love of the medium.

More Richard Avedon Photos

Carmen Dell’Orefice, October 1957 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Elise Daniels Pre-Catelan, Paris, August 1948 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Carmen Dell’Orefice, Folies Bergeres, Harper’s Bazaar, 1957 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

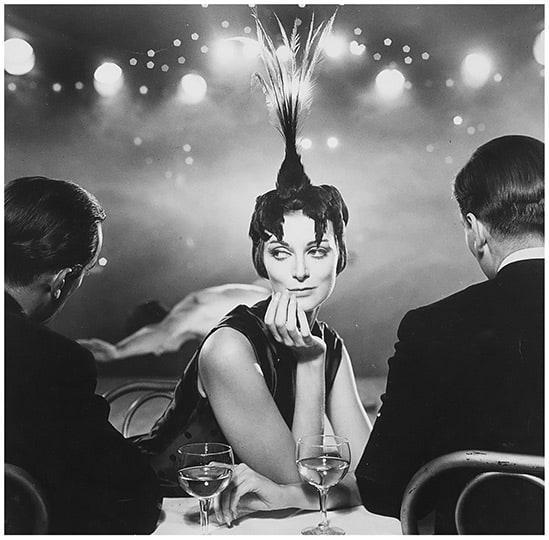

Suzy Parker and Robin Tattersall, Moulin Rouge, Paris, August 1957 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Elise Daniels with Street Performers, Le Marais, Paris, August 1948 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

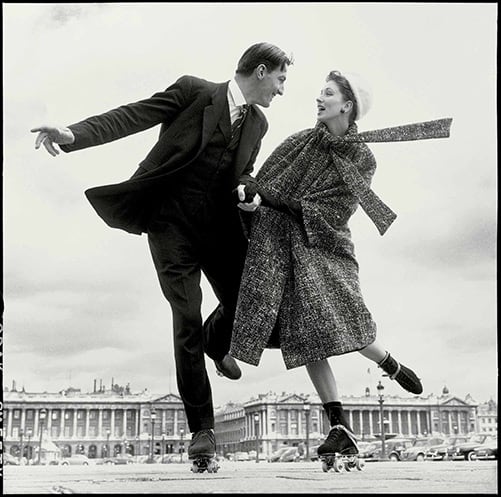

Suzy Parker and Robin Tattersall, Place de la Concorde, Paris, August 1956 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Dovima with Sacha, Cloche by Balenciaga, Paris, August 1955 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Suzy Parker with Robin Tattersall and Gardner McKay, Café des Beaux-Arts, Paris, August 1956 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Buster Keaton, New York, September 1952 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Audrey Hepburn in front of “Winged Victory at Samothrace” in the Louvre, Funny Face, 1957 ©Paramount/The Richard Avedon Foundation

Fred Astaire, Paris 1956 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Malcolm X, New York City, March 1963 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Elizabeth Taylor, cock feathers by Anello of Emme, New York, July 1964 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

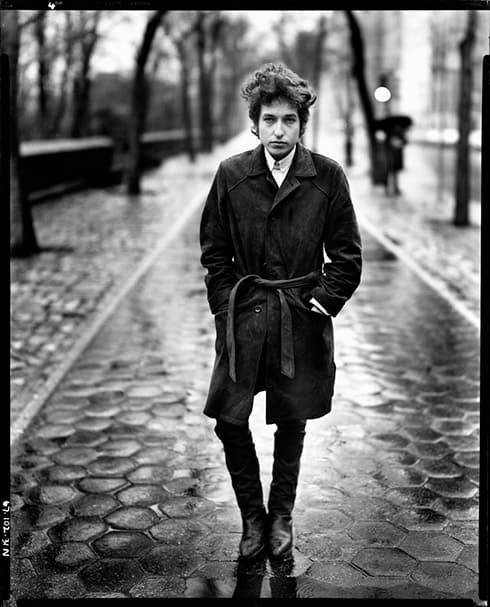

Bob Dylan,New York City, February 1965 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

The Beatles, 1967 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

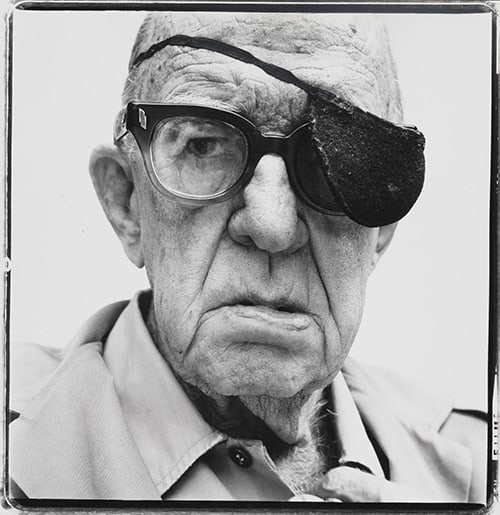

John Ford, Bel Air, California April 1972 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

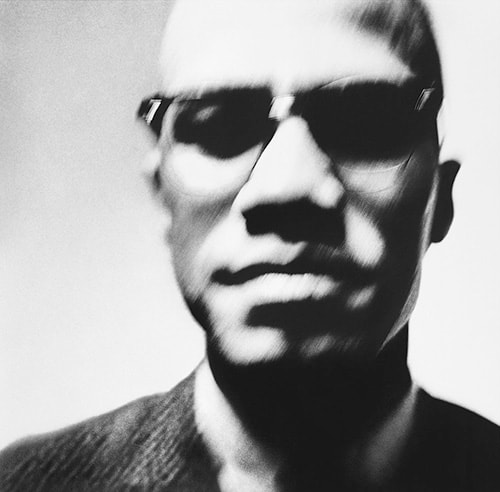

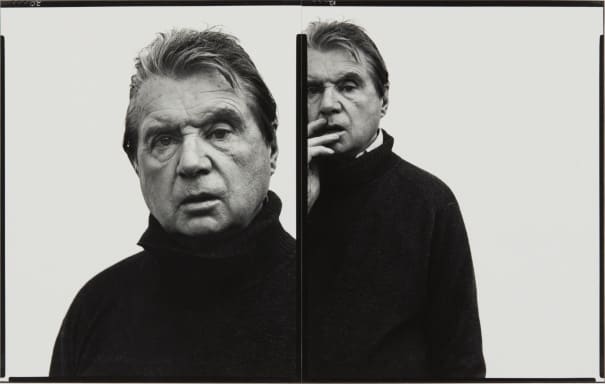

Francis Bacon, Paris, April 1979 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Lauren Hutton, Great Exuma, Bahamas, October 1968 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Nadja Auermann, The Comforts Portfolio, #06, A Fable in 24 Episodes, Montauk, New York, August 1995 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

You can view more Richard Avedon photos here and here

Fact Check

With every profile article we produce, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Avedon’s work, his life, his photography techniques or how he has had an impact on you then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

The website was put together by photographers for photographers, so we can all learn from the masters like Richard Avedon. The more links we have to us, the easier it will be for others to find the website.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Recommended Richard Avedon Links

To see more of Richard Avedon’s work, visit the Avedon Foundation. Also, check out the free Richard Avedon iPad application

Best Interview and Resource Links

Assisting Avedon – Website of former Assistant Earl Steinbicker

The Secrets of Avedon and his Legendary Studio

Richard Avedon and Irving Penn Workshop Transcript – Alexey Brodovitch Workshop, Session Notes: Design Laboratory, 1964

Sources

Avedon Foundation

Assisting Avedon, Earl Steinbicker

A Woman Entering a Taxi in the Rain, New Yorker, Winthrop Sargeant, November 1958

Richard Avedon and Irving Penn Workshop Transcript, 1964

The Secrets of Avedon and his Legendary Studio, Bill Shapiro, Ceros, 2019

Tim Walker: ‘There’s an extremity to my interest in beauty, The Guardian, Sept 2019

American Photo March-April 1994

The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (MIT Press)

American Photo September-October 2002

Visual Poetry: A Creative Guide for Making Engaging Digital Photographs, Chris Orwig

American Photo January-February 2005

Annie Leibovitz at Work, Annie Leibovitz, 2008 (Random House)

Regarding Heroes, Yousuf Karsh, David Travis, 2009 (Godine)

An Autobiography, Richard Avedon (Random House)

Avedon: Evidence (Random House)

Avedon: Fashion 1944-2000 (Harry N. Abrams)

In the America West: Richard Avedon (Harry N. Abrams)

Richard Avedon: Woman in the Mirror (Schirmer Mosel)

Avedon: Something Personal, Norma Stevens and Steven M.L. Aronson (Spiegel & Grau)

Avedon at Work: In the American West, Laura Wilson (University of Texas)

American Masters Series: Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light. Helen Whitney. 1996

Charlie Rose Interviews, PBS, 3 x episodes (October 5, 1993, November 1, 1995 and November 26, 1999)