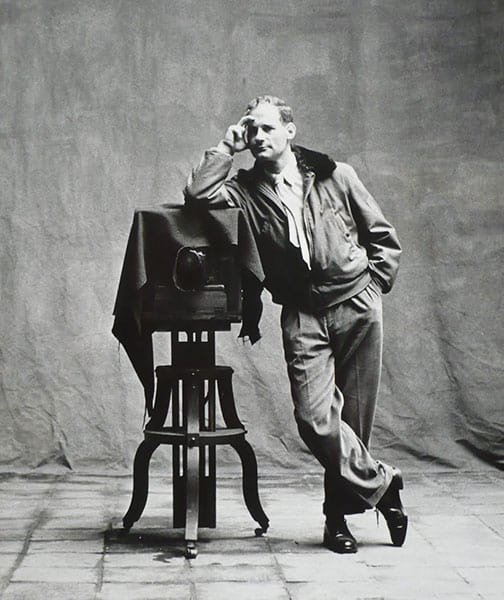

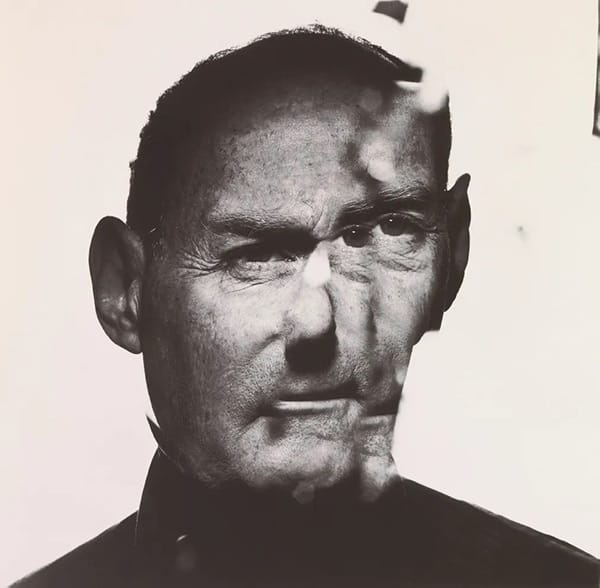

Irving Penn is widely acknowledged as one of the most important and influential photographers of the twentieth century.

In his six decade career, Penn was able to combine the precision of seeing with the invention of form.

Penn was not only an exceptional portraitist and a master of still life, but he was also a great innovator of fashion photography.

His fashion work bridged the gap between art and commerce and helped redefine the language of fashion photography in the process.

He shot a remarkable 165 cover photos for Vogue over sixty years – making him the most prolific photographer in the magazine’s history.

He was one of the first photographers to shoot against a simple plain background – a technique that is now used in every studio around the world.

Penn’s ability to use light, shadow, and space to produce still lifes and portraits that are both evocative and provocative is masterful.

In this article, we’ll be taking a closer look at the work of one of the great masters of twentieth-century photography, Mr. Irving Penn.

Related: 30 Brilliant Irving Penn Quotes to Bookmark

Editor note: If you find our Irving Penn profile helpful then we would be grateful if you could share it with others. Thanks for your continued support.

A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart, leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.

Irving Penn

Table of Contents

Irving Penn Biography

Name: Irving Penn

Nationality: American

Genre: Portrait, Fashion, Nudes, Still-life, Advertising, Travel

Born: 16 June 1917 – Plainfield, New Jersey

Died: 7 October 2009 (92 years old)

Early Career

Penn started his career as a designer before transitioning across to photography. He studied under Alexey Brodovitch at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts, Philadelphia) from 1934 to 1938.

Brodovitch recognized Penn’s talent and invited him to work at Harper’s Bazaar on some design projects during school vacations.

After graduating, Penn worked as a freelance designer in New York from 1938 to 1940. During this time, he purchased his first camera, a Rolleiflex, and wandered the streets of New York on weekends taking photographs. A few of his early images were printed as illustrations in Harper’s Bazaar.

From 1940 and 1941 he worked as an advertising designer for the Saks Fifth Avenue department store. However, the young Penn wished to explore the world and decided to head to Mexico in 1941. He traveled by train, on short trips across the southern United States.

In Mexico, Penn painted for a year in a studio in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City, and took photographs. Dissatisfied with his paintings, though, he destroyed them and returned to New York.

Irving Penn and Vogue

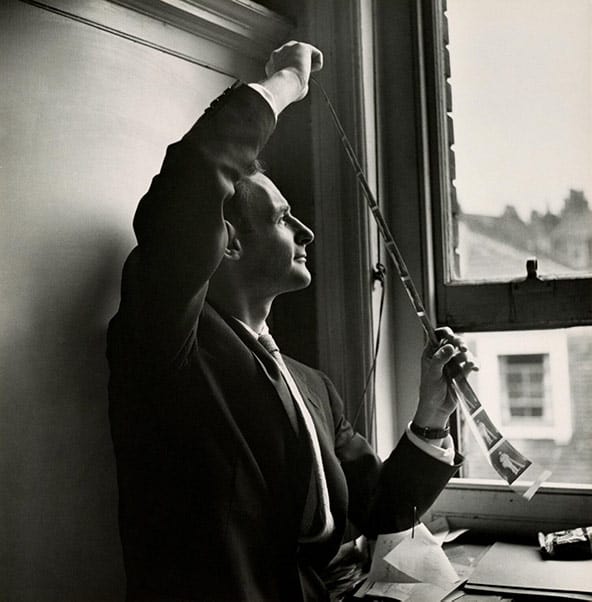

In 1943, Penn was hired by Alexander Liberman, the art director of Vogue, as his assistant. Liberman recognized Penn’s photographic talent and urged him to pursue a career in photography.

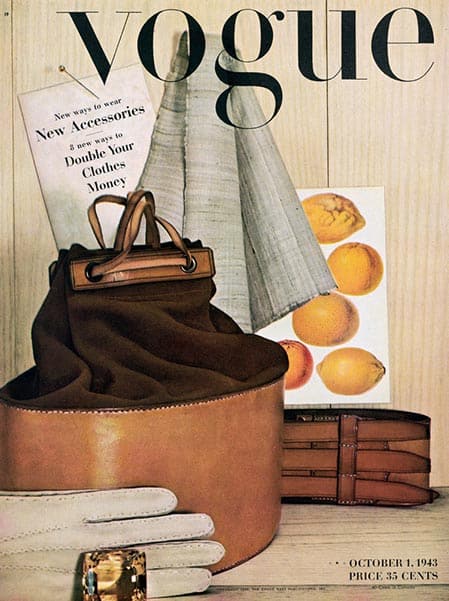

Penn’s first cover, an elegant still-life, appeared in the October 1943 edition of the magazine. Penn would eventually photograph 165 covers for Vogue over sixty years.

During the war years, Penn served as an ambulance driver and photographer in the American Field Service with the British Army in India and Italy.

In 1948, following a photographic assignment for Vogue in Peru, Penn stayed behind to spend Christmas in the historic city of Cuzco. There he photographed the indigenous peoples, creating works that are simultaneously still-life’s and portraits.

Between Vogue assignments, Penn continued to experiment with his work. In 1949, he began photographing the female nude and created prints using a complex bleaching technique for the first time.

Penn married fashion model and muse Lisa Fonssagrives in 1950. His photographs of her frequently show her slim elegance, placed in the center of the frame with few props.

Finding his Style

Penn also worked on a series of “small trades” people. For the project, he visited New York, Paris, and London and photographed unrecognized tradespeople including young butchers, a coalman, a telegraph messenger, pastry cooks, and even a balloon seller, all posing formally in their work clothes and holding the tools of their trade.

It was this series that saw the genesis of what was to become characteristic of his portrait style: subjects posed against a plain background. He also placed his subjects in corner of the frame and lighted subjects from the side.

In the late ’60s, Penn put together a traveling studio for a series of ethnographic essays for Vogue. From 1967 to 1971, he traveled to Dahomey, Cameroon, Nepal, Morocco, and New Guinea.

Penn used his signature style – plain background and a single source light – to photograph these ethnographic images, resulting in a unique body of work that looked completely different from anything seen before.

Penn’s mastery of still life and ability to transform everyday objects to the realm of art was particularly seen in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1977. The museum exhibited photographs of twisted paper, a paper cup, and cigarette butts, which Penn printed using platinum paper.

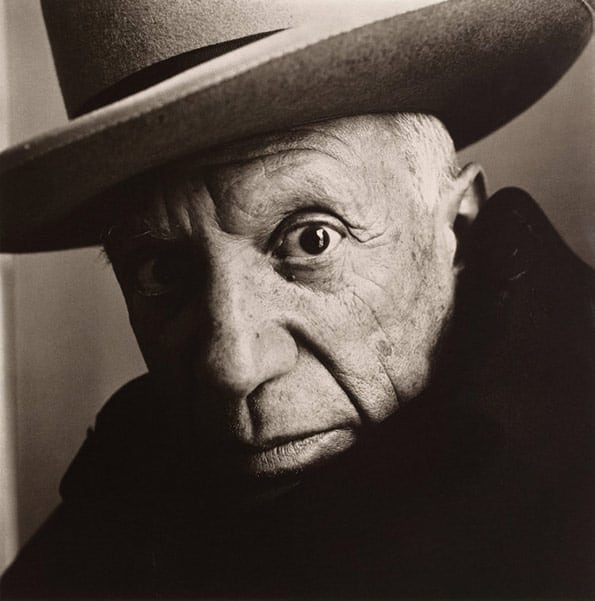

Throughout his career, Penn photographed celebrities, politicians, and artists, including Alfred Hitchcock, Audrey Hepburn, Pablo Picasso, Grace Kelly, Henry Kissinger, Gore Vidal, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Yves St. Laurent.

Mature Period and Legacy

Penn’s creativity flourished during the last decades of his life. His studio in New York continued to be busy with advertising, magazine and personal work, as well as exhibition and print projects.

His innovative portraits, still life, fashion, and beauty photographs continued to appear in Vogue right up until the end of his life.

After the death of Lisa in 1992, Penn found solace in his work and in the structure of his studio schedule, and he would paint in his spare time. In 1997, he donated prints and archival material to the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 2009, Penn died in New York, at the age of 92. During his lifetime, he established The Irving Penn Foundation and published several books including Moments Preserved (1960), Passage (1991), Still Life (2001), and A Notebook at Random (2004)

His work has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and many more galleries. He was represented by Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York City.

Photography Style

- Master of studio photography

- Less is more, simplification and elimination

- Capturing authenticity

- Use of plain background, single color or theatre curtain

- Black and white for portraiture

- Color for beauty and still-life

- Use of conventional north light (single source sidelight: either natural, tungsten or strobe)

- High contrast printing, a strong play between dark and light

Irving Penn worked across a variety of genres throughout his long career. In the next section, we’ll try to breakdown each genre and Penn’s working methods in more detail.

The greatest privilege I’ve had in photography is a change of diet.

Irving Penn

Portraiture

Penn’s distinctive style came from shooting his subjects in the studio and taking them out of their natural environment.

His subjects were posed against a plain background, typically a theater curtain found in Paris that he kept in his studio throughout his career.

Subjects are lighted from the side from either by window light or a single light source that is used to replicate the look of Penn’s favored northern light (see lighting section below.)

He applied the same approach whether he was photographing aborigine tribesmen, movie stars, or even the Hells Angels.

In portrait photography, there is something more profound that we seek inside a person while being painfully aware that a limitation of our medium is that the inside is recordable only insofar as is apparent on the outside.

Irving Penn

In the 1940s, Penn placed his sitters in a narrow corner space, which was created by angling two-stage flats to touch along their vertical edges. The set, both physically and psychologically confined the sitters, resulting in unique portraits.

Finding his Portrait Style

A decade later, Irving Penn adopted a new direct, close-up approach to photographing subjects. He used the same backdrop for all his portraits. He was a big believer in “simplification and elimination.”

Penn wanted his portraits to be both complete and profound, like the works of painters Goya, Daumier, and Toulouse-Lautrec who he greatly admired.

I feed on art more than I ever do on photographs. I can admire photography, but I wouldn’t go to it out of hunger.

Irving Penn

The reason Penn used a simple background was to isolate his subjects, so the images were free from distraction and surplus information. This allowed the viewer to concentrate on the subject and the subject only.

This may be the reason the majority of his portraits are black and white, as color tends to add another element within the frame that could potentially distract the viewer.

Sensitive people faced with the prospect of a camera portrait put on a face they think is the one they would like to show the world. Very often what lies behind the façade is rare and more wonderful than the subject knows or dares to believe.

Irving Penn

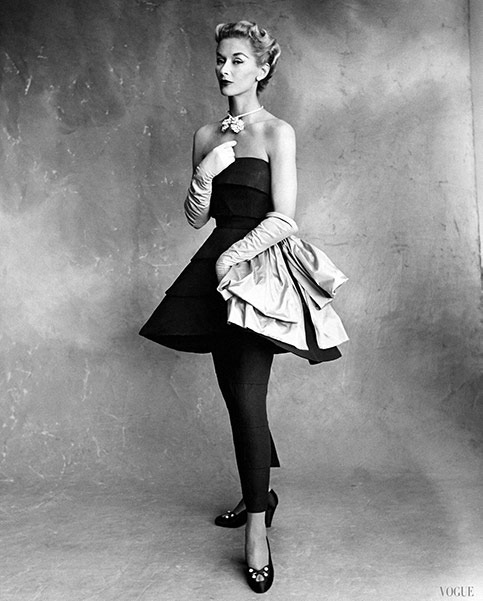

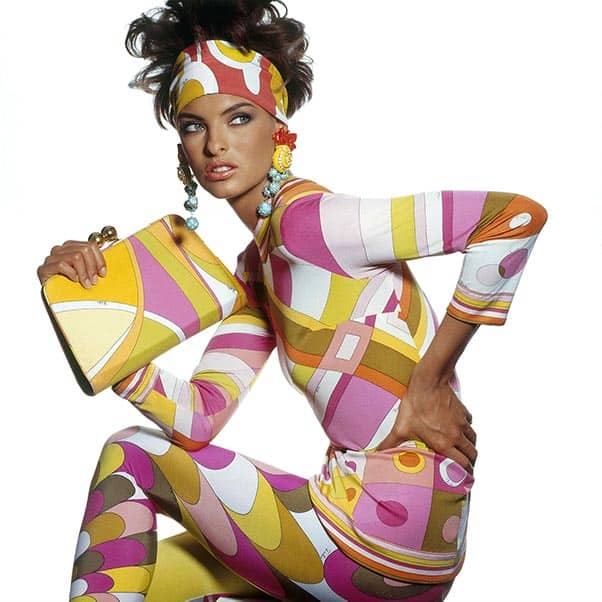

Fashion

Instead of shooting on location or using elaborate props like many early fashion photographers, Penn instead drew attention to the clothing and accessories and photographed models, as he did with his portraiture, isolated against simple backdrops.

Make things manageable enough to record them, to prune away anything inconsequential… Because less is more.

Irving Penn

As one of the first photographers to emphasize style over context, he helped to revolutionize the genre of fashion photography.

A fashion picture is a portrait just as a portrait is a fashion picture.

Irving Penn

Penn was infamous for making his models repeat the same gesture, movement, or position for an entire morning. When his models showed signs of fatigue, he would then get down to business.

I am going to find what is permanent in this face. Truth comes with fatigue. He displays himself just as he is, just as he did not want to look.

He was also known to take a lot of photographs – sometimes over a hundred rolls per photoshoot. His assistants were certainly kept busy.

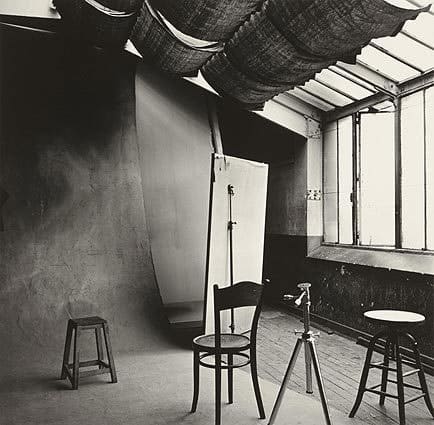

It should also be noted that his studio was a calm and professional place of work – Penn was an artist painting with light. He had already sketched out the idea, had the image he wanted in his head, and now had to mount the image on film.

Former Vogue Editor-in-Chief Diana Vreeland once said: “Irving Penn’s studio is like a cathedral. David Bailey’s studio is like a nightclub.”

Nudes

Penn began photographing nudes in 1949 about the same time his career as a fashion photographer was established. His approach to nudes was completely different from his commercial work though.

He devised a technique of bleaching and re-developing each print to create high contrast areas that enhance the texture and volume of the image.

In terms of the images, his models are positioned either seated or lying down, and they are mostly tightly framed. He also used a lot of top light. There is a mysterious quality to his nude images, which makes them incredibly powerful.

Still Life

Penn’s fascination with still life is evident in the dramatic range of photography he has produced in this genre.

His first assignment as a Vogue studio photographer was a still-life cover, and over the years he completed many striking still-life product shots.

Penn began taking still-life photos of flowers in the 1960s. This led to a book of floral studies, Flowers, published in 1980. He said he was drawn to flowers considerably “after they’ve passed the point of perfection.”

In the 1970s, Penn continued the theme of visual imperfection and produced a series of still-life’s using memento mori objects (a reminder of the inevitability of death) such as cigarette butts, old clothing, and decaying fruit and vegetables.

He successfully challenged the traditional idea of what we consider beautiful, giving common street trash the full studio treatment. Ironically, these photographs are the antithesis of the consumer products Penn shot commercially.

Photographing a cake can be art too.

Irving Penn

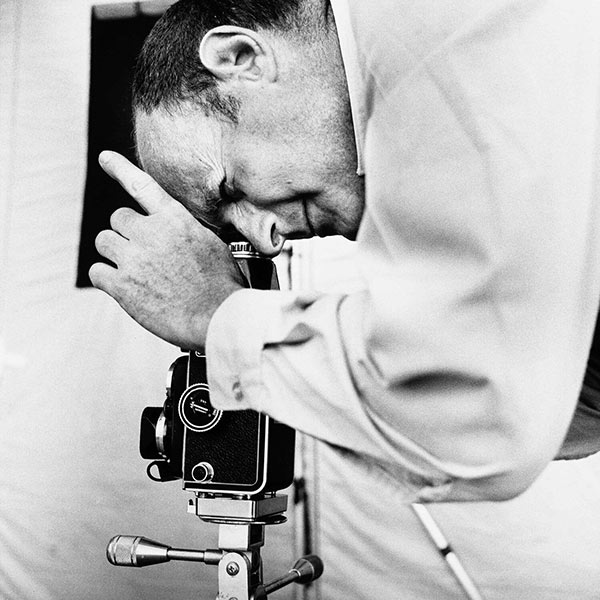

What Camera Did Irving Penn Use?

- Rolleiflex

- Deardorff Large format view (4-by-5-inch and 8-by-10-inch models)

- Leica

- Nikon F

- Banquet Large Format

Penn purchased his first camera, a twin-lens medium format Rolleiflex around 1938 after graduating. He continued to use the same model right until the end of his career, some sixty years later.

For his studio work for Vogue, Penn frequently used a Deardorff large format view camera (both the 4×5 and 8×10 models).

Penn began using a 35mm Leica camera for his travel assignments for Vogue in 1950.

In the late 1950s, Penn switched from Leica to a Nikon, trading the rangefinder-style Leica camera for the newer single-lens reflex design and the telephoto lens.

In a burst of romantic passion for this new apparatus (forgetting gratitude to the Leica and with even a certain amount of disloyalty) I diverted myself of all our studios elaborate and superb Leica equipment, taking a terrible financial beating in the process, not finding a panacea and exchanging one set of headaches for another.

Irving Penn

Penn would later come to appreciate the flexibility of the new system and continue to use it for the rest of his career.

In 1979, Penn picked up a Banquet camera, a large format view camera, that was popular in the early twentieth century for taking group portraits in formal situations.

What Film Did Penn Use?

Penn mainly used Kodak black and white film for his portraits, either Super XX, Plus-X, or Tri-X (it seems any Kodak film with an X). For his fashion, beauty, and still-life photography he preferred to use color film.

After looking at my notes and reviewing his contact sheets it looks like he used both Fuji and Kodak for his color work. For his later studio photography, he used Kodak Ektachrome E200 slide-film.

In his book, World’s in a Small Room, Penn states that most of his photography in the book was shot on Kodak Tri-X and exposed at 160 ASA, or 80 to 125 ASA for very dark skins. Development was usually in Ethol UFG for 3 to 5 minutes at 68F.

Irving Penn Lighting Technique

Penn’s lighting would change depending on what genre of photography he was shooting and the location.

Below I’m going to try and cover Penn’s portrait lighting in detail (or as best as I can). His fashion photography would require another article.

Whenever possible, Penn would try and use natural north light, which is also favored by artists. This makes sense as he was heavily influenced by painters.

I share with many people the feeling that there is a sweetness and constancy to light that falls into a studio from the north sky that sets it beyond any other illumination. It is a light of such penetrating clarity that even a simple object lying by chance in such a light takes on an inner glow, almost a voluptuousness.

Irving Penn

In many of his pictures, the lighting is fairly directional and comes from one side, which creates a dramatic fall-off across the frame.

Penn makes everything extremely hard for himself. He employs no gadgets, no special props, nothing but the simplest lighting – probably a one-source light coming from the side of the sitter’s head.

Cecil Beaton, writing in 1975

Lighting Method

To achieve this, he used either window light or his portable studio. In his studio, he had floor to ceiling glass and large skylights installed.

If the light wasn’t strong enough (or there wasn’t any window light available) then he would augment the existing light or replicate window light with either tungsten, strobes, and even cheap hardware clamp lights. Whatever got the job done and gave him the quality of light he needed.

In my windowless New York studio, I designed a bank of tungsten to more or less simulate a skylight. The bank was constructed in a metal frame moved by hand pulley on a ceiling track. I found this to be an agreeable light for the formalized arrangements of people and still-life’s I meant to photograph. A drawback of course was the considerable heat of the bulbs and the long exposure times required. For still life’s, exposures could sometimes be hours long.

Irving Penn

Penn began experimenting with strobe lighting as early as 1952 when he was first introduced to the technology by colleague Leslie Gill.

He also used scrims, flags, drapes, mirrors, umbrellas, and reflectors to shape and control the light.

Editor note: If you have anything further you wish to add, specifically to do with Penn’s technique (lighting, printing, etc) then send us an email so we can update the article.

Platinum Printing Process

In 1964, Penn used the platinum/palladium printing process for the first time – a printing technique that was popular at the turn of the century.

The process involved applying platinum rather than silver on the printing paper. He would then expose and develop the negative then repeat until satisfied with the print.

After he perfected the technique, Penn went back and reprinted a lot of his earlier work.

Sometime in 1964, I realized that I was a victim of a printmaking obsession, a condition that persists today.

Irving Penn

Here is a short video from his former assistant that explains the technique:

Other Resources

Recommended Irving Penn Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

Irving Penn Videos

On Location in Morocco, 1971

The Portraits of Irving Penn – The Art of Photography

Irving Penn Photos

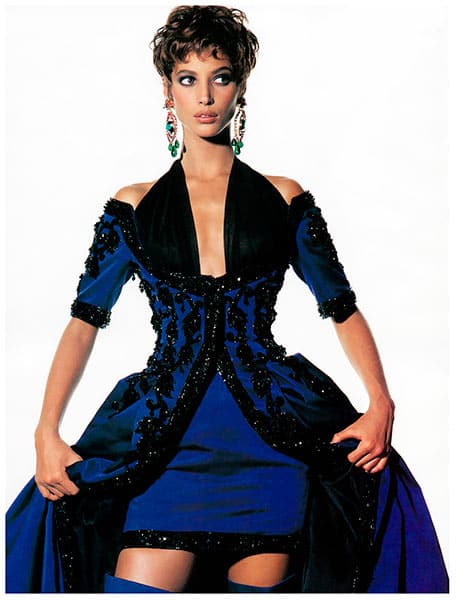

Christy Turlington in Chanel, Vogue, 1990 © Condé Nast

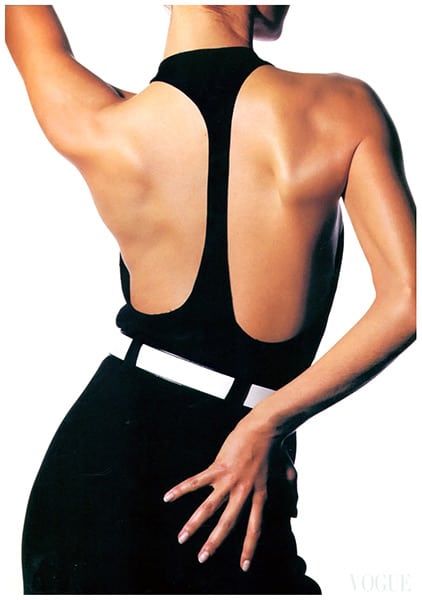

Karen Mulder, Vogue, April 1991 © Condé Nast

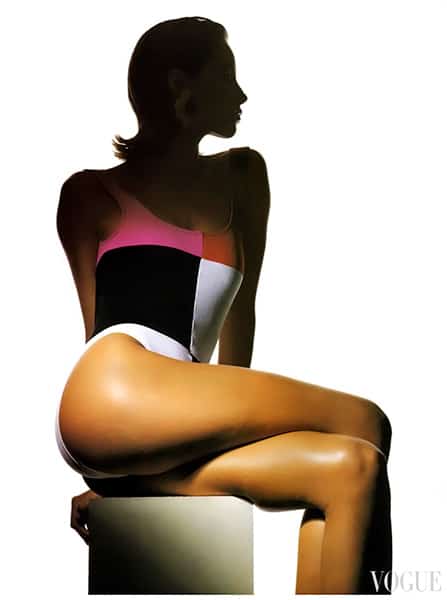

Christy Turlington, Strong Suits, Vogue, December 1989 © Condé Nast

Girl with Tobacco on Tongue, Mary Jane Russell, New York, 1951 © Condé Nast

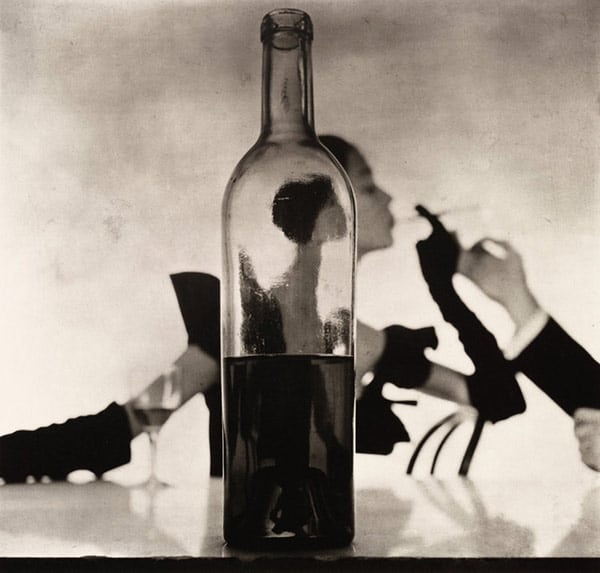

Man Lighting Girl’s Cigarette, Jean Patchett, New York, 1949 © The Irving Penn Foundation

White Face with Color Smears, New York, 1986 © Condé Nast

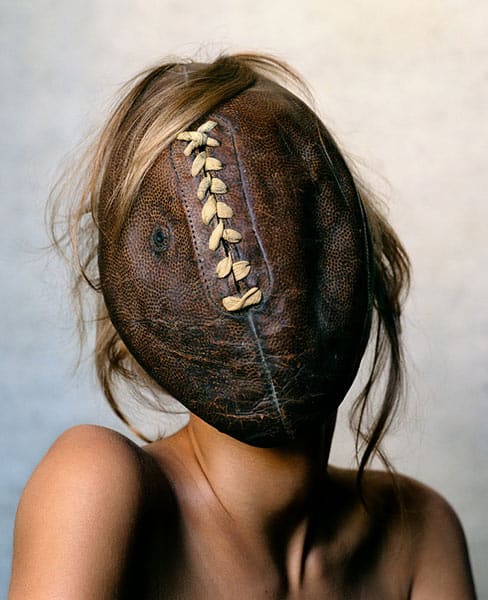

Football Face, November 2002 © The Irving Penn Foundation

Moroccan Fantasia, 1951 © Condé Nast

Young Berber Shepherdess, Morocco, 1971 © The Irving Penn Foundation

Looking for more Irving Penn photos? Then head over to the Irving Penn archive and The Met Museum.

Further Reading

Alexey Brodovitch Workshop Transcript – Conversation between Richard Avedon and Irving Penn from 1964 session. The legendary photographers discuss their photography style, projects, and commercial work.

Irving Penn Notebook – Copy of Penn’s notebook. Despite being difficult to read, it’s worth printing to help understand his process better.

The Art Institute of Chicago: Irving Penn Archives – Lots of great information about the master photographer that you won’t find anywhere else.

Fact Check

With every Photographer profile article, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Irving Penn’s work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

Photogpedia is free to read. If you find this article or any of our other articles helpful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online.

If you would like to contribute an article about your favorite photographer, then read our write for us page.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Related Articles

- Richard Avedon: The Million Dollar Man

- Yousuf Karsh: The Master of Portrait Photography

- Horst P Horst: The Photographer of Style

Sources

Irving Penn is Difficult, Can’t you Tell, New York Times, 1991

Obituary, The Guardian, 2009

Irving Penn: Small Trades , The J Paul Getty Museum, 2009

Centennial, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017

Irving Penn at the Met, Vogue, 2017

How Irving Penn ‘changed the way people saw the world, Christies, 2020

Celebrating the work of Irving Penn, The Guardian, January 2021

The Irving Penn Foundation

Irving Penn Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago

Richard Avedon and Irving Penn Workshop Transcript, 1964

Passage, Knopf, 1991

A Career in Photography, Bullfinch, 1997

Irving Penn: Centennial, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017

Encyclopedia of Twentieth-century Photography, Routledge, 2005