Henri Cartier-Bresson was the world’s greatest documentary photographer and a master of candid photography. He is perhaps the most significant and influential photographer of the twentieth century.

Cartier-Bresson did for photography what Picasso did for painting. He was a photographic visionary who helped changed the way we see photographs and was a pioneer of the street photography genre. He also co-founded the legendary photo agency, Magnum Photos.

His working methods and abilities are part of photographic lore: he had an uncanny talent for remaining invisible to his subjects; his compositions were perfectly balanced and he rarely cropped his images; and he had an instinct for capturing the most telling moments from a scene.

Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment” – a fleeting meaningful instant captured by the camera – shaped modern-day street photography and inspired generations of photojournalists.

When a photographer raises his camera at something that is taking place in front of him, there is one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance. Photography must seize upon this moment.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson’s black-and-white photos are among the most iconic in photography, including his powerful images of some of the major political moments in the 20th century.

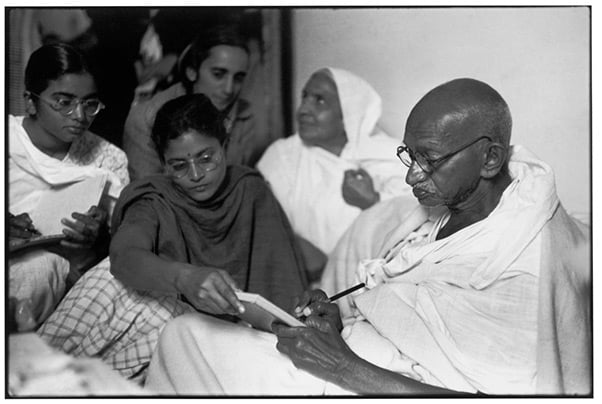

He photographed Gandhi literally minutes before he was assassinated, and he stayed to cover the funeral. In 1954, he was the first Western photographer to be allowed to photograph in the Soviet Union after the death of dictator Josef Stalin and the end of his brutal rule.

He had a knack for being in the right part of the world just as history was unfolding. He said his intention was to “trap life” and “preserve it in the act of being lived.”

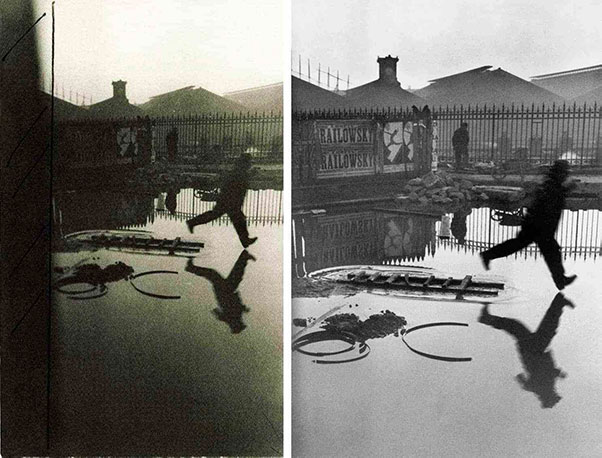

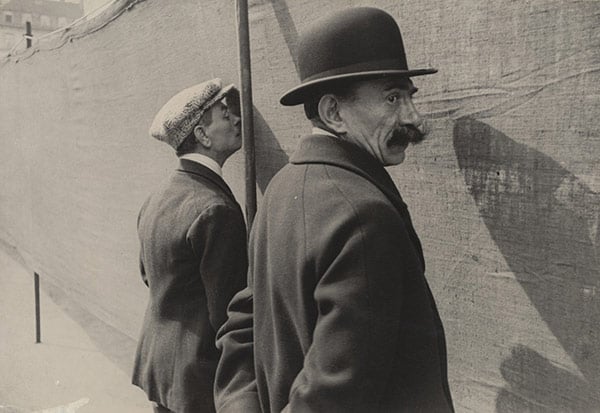

Among his best-known photographs were a man and his reflection frozen in time as he leaps across a giant puddle behind Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris, two men at a peephole in Brussels, and a cyclist speeding around a curve in the shape of the spiraling staircase from which Cartier-Bresson took the image.

Often the scene is quite ordinary – a woman eating in a cafe, children playing, lovers kissing. But in Cartier-Bresson’s pictures, it takes on a significance that touches everyone.

Most photographers (at the highest level) take maybe two or three great photographs in their career, Cartier-Bresson shot well over a dozen. With apparent ease, he succeeded in producing one masterpiece after another.

Cartier-Bresson is the greatest photographer of the 20th century. He is like Tolstoy was to literature. His pictures go beyond any breaking down of what a picture is supposed to be, or any intellectualizing about it. If you had a career that had five great photographs, that would be pretty good. He has made hundreds of them. Nobody else has that track record.

Richard Avedon

In this article, we will take a closer look at Cartier-Bresson’s career and photography style. This will be another long article, so feel free to use the table of contents below, and skip ahead to whatever section interests you.

If you find any of the information helpful then we would be grateful if you could share a link to the article through the usual channels (websites, forums, social media, etc).

Editor note: This Henri Cartier-Bresson article took over 3 weeks to research and write – sharing takes just a couple of minutes and doesn’t cost you anything. Thanks for your support in advance.

Table of Contents

Henri Cartier-Bresson Biography

Name: Henri Cartier-Bresson

Nationality: French

Genre: Street, Photojournalism, Documentary, Portraiture

Born: August 22, 1908 – Chanteloup, Seine-et-Marne, France

Died: August 3, 2004 (95 Years) – Montjustin, France

Early Life

Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloup, Seine-et-Marne, on August 22, 1908. He was the oldest of five children born to Andre Cartier-Bresson, a wealthy textile manufacturer, and Marthe Leverdier, a daughter of cotton merchants and wealthy landowners.

Bresson was educated in Paris at the Lyce ́e Condorcet. He first became interested in photography as a teenager, after seeing the photographs of Romanian photographer, Martin Munkacsi.

Cartier-Bresson said the first photograph that overwhelmed him was Munkasci’s photograph of three African children running towards the water of Lake Tanganyika. That image made him realize, “that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant.”

In 1927, he studied painting under Andre ́Lhote, who had been an early practitioner of Cubism. Cartier-Bresson stated that Lhote taught him everything he knew about photography including the importance of composition. He also spent some time studying with the portrait painter Emile Blanche.

Cartier-Bresson then moved to England and studied English literature and art at Cambridge University, but dropped out after one year. He returned to France in 1929 and was given his first camera, a Box Brownie from the American expatriate Harry Crosby.

In 1930, Bresson began his military service with the French Army and was stationed at Le Bourget, near Paris.

Africa, Hunting and Near Death Experience

Upon his discharge, filled with poetry and literature and looking for adventure, he set off for West Africa and the French colony of Coˆte d’Ivoire to hunt.

Several months after arriving in Africa, he contracted blackwater fever (a severe malaria infection) and almost died. Later when describing the experience, he said a witch doctor got him out of a coma and while he was sick, he had sent a postcard to his grandfather detailing his funeral arrangements.

In 1931, Cartier-Bresson returned to Marseilles to recuperate. The trip to Africa wasn’t a complete waste. Learning how to hunt would prove useful for his photography and waiting for the decisive moment.

Cartier-Bresson would later say, “I adore shooting photography; it’s like being a hunter. But some hunters are vegetarians – which is my relationship to photography.” Although he loved the process of making photos, for Cartier-Bresson the chase was always better than the catch.

Enter Photography

That same year, he acquired his first professional camera, a small, lightweight Leica with a 50mm lens. He found the camera gave him a sense of independence and unity with his environment and often referred to it as an extension of his eye.

As he was independently wealthy, and living off a generous allowance from his father, Cartier-Bresson would spend most of his days roaming the streets experimenting with his new passion.

I had blackwater fever in Africa and was now obliged to convalesce. I went to Marseille. A small allowance enabled me to get along, and I worked with enjoyment. I had just discovered the Leica. It became the extension of my eye, and I have never been separated from it since I found it.

I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life– to preserve life in the act of living. Above all, I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was unrolling before my eyes.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Not long after purchasing the camera, he shot one of his most recognizable images, Behind Gare St. Lazar.

He stuck his camera between the slats of a fence near the St Lazare railway station in Paris at the right moment and captured the figure of a leaping man, which mirrored the dancers on the posters on the wall behind him.

Over the next few years, Cartier-Bresson photographed widely across Europe and the United States and was soon given assignments by magazines such as Life and Harper’s Bazaar.

In 1932 he was given his first exhibition in America by Julien Levy, a friend of Jean Cocteau. While in New York, he met Paul Strand, who at that time was making films.

Filmmaking and Renoir

Inspired by Strand, when he returned to France Cartier-Bresson secured the position of a second assistant on Jean Renoir’s A Day in the Country and The Rules of the Game.

He was also involved in a propaganda film the famous director made for the French Communist Party that denounced France’s prominent families in France, Cartier-Bresson’s own among them.

On his experience with Renoir, Cartier-Bresson said “Jean knew very well that I would never make a feature film. He saw that I had no imagination.”

The War Years

In 1940, with the German invasion of France, Cartier-Bresson, who was serving in the Army’s Film and Photo Unit was captured and taken prisoner. He spent 35 months in prisoner-of-war camps, escaping twice, only to be recaptured.

On his third escape attempt, in 1943, he succeeded, and he hid on a farm in Touraine until French Resistance fighters secured false papers that allowed him to travel in France. Back in Paris, he once again took up photography as a member of the Resistance.

He established a photo division within the French underground to document the German occupation as well as their eventual retreat, an experience which would later shape his ideas about the photo agency, Magnum when it was established in 1947.

Post-War

Following France’s liberation in 1944, the United States Office of War Information hired Cartier-Bresson to direct a film about the homecoming of French prisoners of war and deportees, La Retour (The Return).

Cartier-Bresson then traveled to New York City, where a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, conceived as a tribute to his work, on the belief that he had been killed in the war, had been planned.

While in the United States, he decided to take some time out to travel and see the country. During this trip, he took signature images such as Harlem, Easter Sunday, 1947, which shows an African-American woman wearing a satin-flower-filled hat framed within the architectural details of a modest brick structure.

Magnum Photos

Returning to Paris in 1947, Cartier-Bresson learned that his associates Robert Capa, David Seymour (Chim), William Vandivert, and George Rodger, had planned to form a cooperative photo agency with offices in New York, Paris, and other world capitals.

Dubbed Magnum Photos, the group named Cartier-Bresson to their board of directors, knowing that he was like-minded and aware of his considerable prestige. The co-operative, the first of its kind, was set up to give freelance photographers greater editorial and financial control of their work.

He was tapped to be in charge of Far Eastern assignments; and his insistence on small format cameras, no supplementary equipment such as flash, tripods, or telephoto lens and the integrity of the frame as photographed – no darkroom manipulation – became the gold standard for postwar photojournalism as well as being highly influential on fine art photography.

Photojournalism

The late 1940s saw the rise of Cartier-Bresson as an international photojournalist. Cartier-Bresson himself, however, strongly refused the title.

Journalism has kept me from going stale, and through photo assignments, I am able to see many new places, but I am not a journalist. I simply sniff around and take the temperature of a place.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

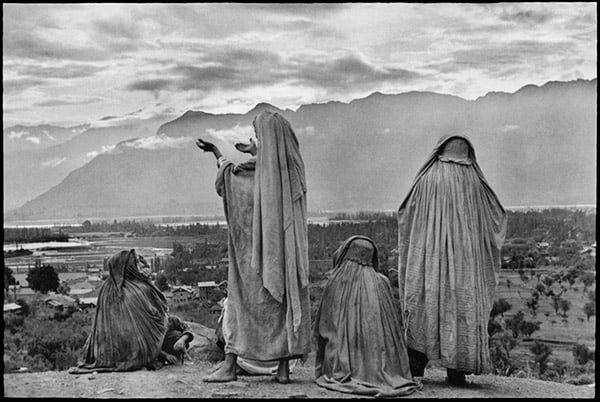

For Magnum, he traveled to China, India – where he photographed Gandhi minutes before he was assassinated – and Indonesia, photographing political events and the people in their streets and homes.

Recognition and The Decisive Moment

By 1952, Cartier-Bresson finally received recognition in his home country.

His first book, Images a`la sauvette (with its English title of The Decisive Moment,) with cover art by Matisse, was published. The book included a large collection of his images, and he elaborates on his techniques and approach to photography. The book remains one of the most influential photography books of all-time.

After The Decisive Moment, he began a long collaboration with eminent fine arts publisher Robert Delpire. This included a book on Balinese theatre, Les Danses a`Bali, featuring text by Antonin Artaud. His book Les Europe ́ens, with cover art by painter Joan Miro’, was published as well.

In 1955, he became the first photographer to be exhibited at the Louvre in France.

On Assignment

One of Cartier-Bresson’s favorite assignments was Moscow in 1954. He was the first foreign photographer to be allowed entrance to the USSR since the death of Stalin the following year. The French photographer set about capturing daily life in his usual candid style. The assignment resulted in a remarkable photo series that was published in Life in 1955.

The 1960s were again a period of intense international travel. He returned to Mexico, where he had made one of his first photographic forays as part of an ethnographic team in the early 1930s. On assignment for Life magazine, he traveled to Cuba during a time of high tension between that country and the United States. He visited Japan and again traveled to India.

Retirement from Photography

Cartier-Bresson ended his relationship with Magnum Photos in 1966. He later said that he had stayed with the agency “two years too long.”

In the late ’60s, he retired from professional photography altogether and focussed instead on documentary film projects. He believed that still photography and its use in pictorial magazines had been superseded by news coverage on television. His films include Impressions of California (1969) and Southern Exposures (1971).

Later Years and Painting

After divorcing his wife of 30 years, the Javanese dancer Ratna Mohini, Cartier-Bresson married the Magnum photographer Martine Franck in 1970.

He recalled in an interview, the time he visited a fortune teller:

There are certain things you can’t just make up. In 1932, she told me that I would marry someone who would not be from India, or from China, but would also not be white. And in 1937 I married a Javanese woman. This fortune teller also told me that the marriage would be difficult and that when I was old, I would marry someone much younger than I and would be very happy.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

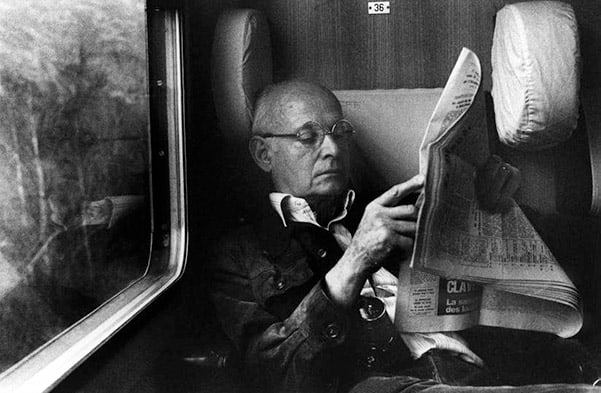

After 1974, he photographed very little, and then often secretly, which he had perfected during his long career as a photojournalist. Working with a small camera that he would often further minimize by covering with black tape any metal parts which might reflect light and catch the eye.

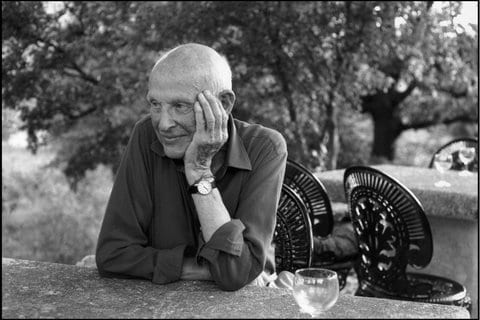

Cartier-Bresson returned to his first love of painting and drawing, and spent his remaining days at his studio near the Place des Victoires or in his apartment overlooking the Tuileries, from which he could see the same views that Monet and Pissarro had painted a century earlier.

Cartier-Bresson’s Legacy

Henri Cartier-Bresson died in the south of France on 5 August 2004 at the age of 95.

In his lifetime he received an extraordinary number of awards, prizes and honorary doctorates. His work has also been exhibited in some of the world’s finest galleries including the Louvre, Museum of Modern Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, and The National Portrait Gallery.

In 2003, shortly before his 95th birthday, Cartier-Bresson along with his wife, Martine and daughter, Mélanie established the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris to preserve the legacy of the iconic photographer. The opening was accompanied by a retrospective exhibition at the French National Library that opened in April 2003.

Photography Style

- Candid, unobtrusive

- Patient, the decisive moment

- Composition: Use of geometry, shape, contrasts, rarely crops

- Black and white imagery

- Storytelling, continuity

- Minimalistic, one camera, one lens

Cartier-Bresson Photography Masterclass

The aim of this section is to provide an introduction to Cartier-Bresson’s photography techniques, which will hopefully inspire you in some way or another.

The following quote from HCB provides an invaluable insight into his photography philosophy:

For me, the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the master of the instant which, in visual terms, questions and decides simultaneously. It is by economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Below you’ll find extracts from various books and interviews with Cartier-Bresson along with a short paragraph to summarise key points.

The Decisive Moment

The phrase The Decisive Moment was first introduced in 1952, as the title of the English edition of Cartier-Bresson’s book, Images a`la sauvette. The French title of the book actually translates as ‘images on the run’ and not the decisive moment as many people assume.

The phrase was actually taken from the 17th-century quote from Cardinal de Retz and is used by Cartier-Bresson in the introduction of the book.

There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment and the masterpiece of good ruling is to know and seize this moment.

Cardinal de Retz

So what does the decisive moment mean? Here is another excerpt from the introduction, which summarises Cartier-Bresson’s own idea of the decisive moment:

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression. Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Working the Scene

The phrase is often used to describe an image that illustrates action, emotion, and the entire story in a single frame.

Your eye must see a composition of an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

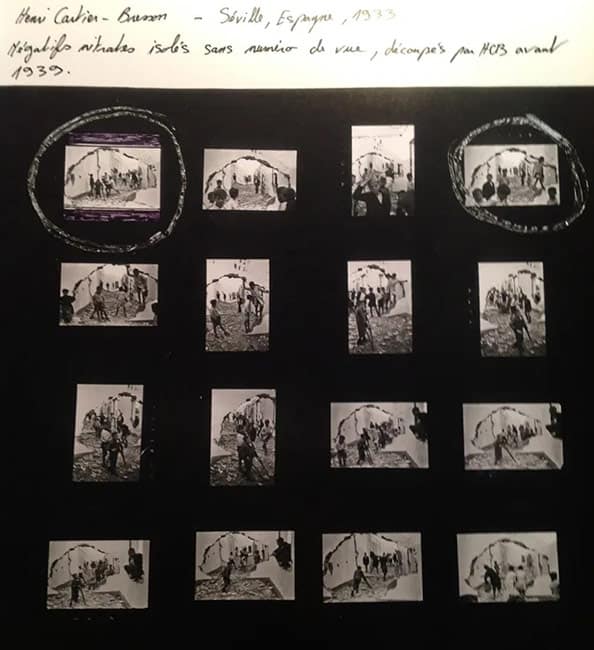

The truth is that Cartier-Bresson didn’t just take one frame, he would find his composition (or story) and “work the scene” taking multiple images (sometimes up to 20 exposures).

Instead of just one decisive moment, there can be up to a dozen decisive moments even within the same scene.

While working, a photographer must reach a precise awareness of what he is trying to do. Sometimes you have the feeling that you have already taken the strongest possible picture of a particular situation or scene; nevertheless, you find yourself compulsively shooting, because you cannot be sure in advance exactly how the situation, the scene, is going to unfold.

You must stay with the scene, just in case the elements of the situation shoot off from the core again. At the same time, it’s essential to avoid shooting like a machine-gunner and burdening yourself with useless recordings which clutter your memory and spoil the exactness of the reportage as a whole.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson was a true observer who recognized the significance or the potential of an event.

He would first find his composition then he would wait for something to enter the frame or a moment to happen to complete the picture. He would often say, “he did not take the picture, rather the picture took him.”

He also liked to compare himself to a fisherman – the only difference is his catch was a moment in time.

Sometimes it happens that you stall, delay, wait for something to happen. Sometimes you have the feeling that here are all the makings of a picture – except for just one thing that seems to be missing. But what one thing? Perhaps someone suddenly walks into your range of view. You follow his progress through the viewfinder. You wait and wait, and then finally you press the button – and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

That’s not to say, he’d wait hours for the right image, he would constantly adapt and respond to the changing circumstances.

My contact sheets may be compared to the way you drive a nail in a plank. First, you give several light taps to build up a rhythm and align the nail with the wood. Then, much more quickly, and with as few strokes as possible, you hit the nail forcefully on the head and drive it in.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Once he knew he had his shot, he then moved on. Sometimes though, you don’t have the luxury of spending time working a scene and in that situation, as HCB explains below, you need to act quickly.

When something happens, you have to be extremely swift. Like an animal and a prey — vroom! You grasp it and people don’t notice that you have taken it.

Very often in a different situation, you can take one picture. You cannot take two. Take a picture and look like a fool, look like a tourist. But if you take two, three pictures, you got trouble. It’s good training to know how far you can go.

When the fruit is ripe, you have to pluck it. Quick! With no indulgence over yourself, but daring. I enjoy very much seeing a good photographer working. There’s an elegance, just like in a bullfight.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Hunting for Photos

Cartier-Bresson would only keep his images if every element of his image (background, subject and composition) were perfect. The subjects of his photos weren’t as important as the spirit of a place, or the moment he was trying to capture.

He traveled extensively and photographed many places including India, Europe, China, Africa and the United States. When he worked on overseas assignments he would take time to familiarise himself with the country.

For example, when he worked on an India assignment, he spent a year getting to know the people, while fully immersing himself in the Indian culture.

Although it is great to shoot street photography in your backyard, it is great to travel as often as you can. Explore different countries and cultures, and it will help inspire your photography and open your eyes.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Trusting your Intuition

That’s not to say that he didn’t shoot in his own backyard – many of his greatest images were taken on the streets of Paris.

Sometimes, the best photography can often be found where you live, you just need to remain as Cartier-Bresson liked to say “lucid” and open to opportunity.

Photography is not documentary, but intuition, a poetic experience. It’s drowning yourself, dissolving yourself, and then sniff, sniff, sniff – being sensitive to coincidence. You can’t go looking for it; you can’t want it, or you won’t get it. First you must lose yourself. Then it happens.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

When selecting subjects, it is often the small details or events that make the best photographs:

In photography, the smallest thing can be a great subject. The little, human detail can become a leitmotiv. We see and show the world around us, but it is an event itself which provokes the organic rhythm of forms.

Cartier-Bresson’s greatest skill perhaps was his ability to thrive on accident or to recognize a situation that held the promise of a happy accident.

His iconic photograph, Behind the Gare de Saint-Lazare (1932) is a perfect example of a happy accident.

While passing a construction site behind the Paris train station, the photographer stuck his lens through the wooden planks of a temporary fence, and without looking through the viewfinder, clicked his shutter and produced one of his most famous photos.

The Art of the Story

Cartier-Bresson believed that it was rare that a single image could show a whole story and a successful picture story is dependant on the sequencing of several complementary images to support the main image of the story.

The elements which, together, can strike sparks from a subject, are often scattered – either in terms of space or time – and bringing them together by force is ”stage management,“ and, I feel, contrived.

But if it is possible to make pictures of the ”core“ as well as the struck-off sparks of the subject, this is a picture-story. The page serves to reunite the complementary elements which are dispersed throughout several photographs.

Related Article: Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Quotes

While shooting, the photographer must build a story, else his work will lack continuity. Unlike the writer, he cannot change: what happens at the decisive moment is recorded forever.

The picture-story involves a joint operation of the brain, the eye, and the heart. The objective of this joint operation is to depict the content of some event which is in the process of unfolding, and to communicate impressions.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

His best work is remarkable for the fact that he completely ignores photographic traditions and the usual dramatic props of the photojournalist.

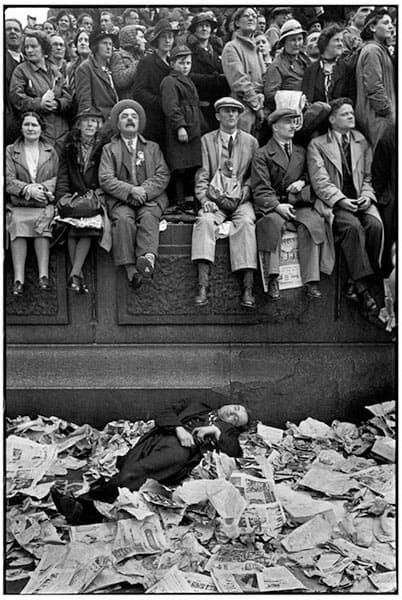

For instance, when Cartier-Bresson covered the coronation of George VI in London in 1937, instead of photographing the procession like every other photojournalist, he turned his camera on the crowd instead.

Work for Yourself and the Story

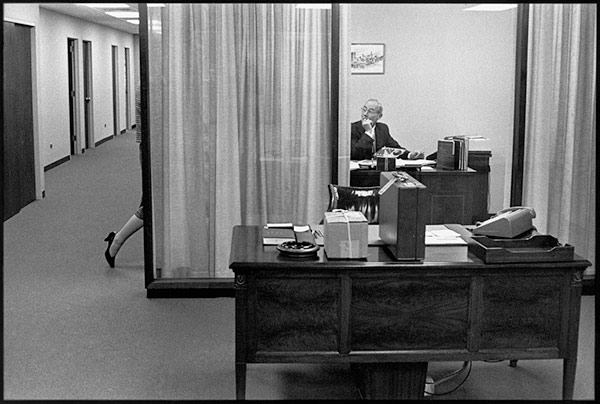

Cartier-Bresson believed that the story is just as much about you and how you see the world.

You have to know in which framework you have to tell your story for the magazine, but you must not work for the magazine… you work for yourself, and the story.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

He wasn’t interested in staged or studio photography and preferred a more candid approach.

’Manufactured’ or staged photography does not concern me. And if I make a judgment it can only be on a psychological or sociological level. There are those who take photographs arranged beforehand and those who go out to discover the image and seize it.

If you’re looking for more of an insight into Cartier-Bresson’s working methods on assignment, then I recommend reading Ishu Patel’s, My Time with Henri Cartier-Bresson. Here’s a small extract from the article:

Over the years he had simplified the technical part of photography to suit his unobtrusive shooting style and still create a technically perfect photograph.

For instance, he judged the light by eye, although he carried a small light meter in his pants pocket. Since he mostly shot in shaded areas he set his F stop at 5.6 or 8 and shutter speed at 1/60th to 1/125th of a second, so he could quickly pay attention to his subject matter. He made it clear that, “technique is not so important to me, but people and their activities are”.

He said, “Think about the photograph before and after, but not during. The secret is to take your time but also to be very quick”. In other words there was to be no cropping of the image later, no dodging or other tricks used in printing. The image captured on film had to stand on its own merits.

Ishu Patel

Editing and Post-Processing

Cartier-Bresson rarely processed film himself and would often send his films to someone he trusted. The same goes for printing. This allowed him to spend more time out shooting instead of in the darkroom.

He says that an image shouldn’t be over-processed and that you should only set out to recreate the mood of the scene you captured.

During the process of enlarging, it is essential to re-create the values and mood of the time the picture was taken; or even to modify the print so as to bring it into line with the intentions of the photographer at the moment he shot it.

Cartier-Bresson believed that if you shoot a bad photo, no amount of post-processing (darkroom work in his day) can make it any better.

The Editing Process

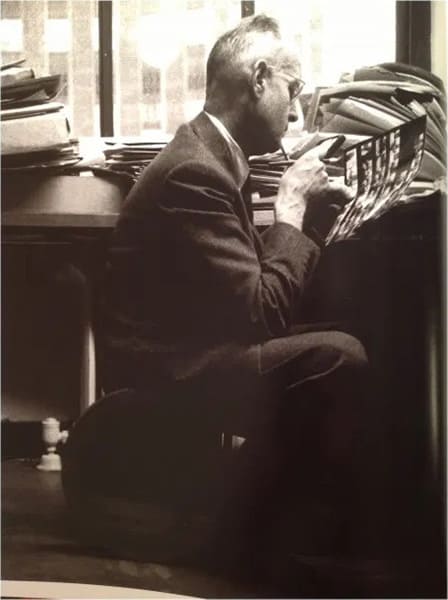

When editing his work, Cartier-Bresson often looked at his contact sheets or prints upside down, so he could judge the merit of his images as a composition, rather than being influenced by content and subject.

For photographers, there are two kinds of selection to be made, and either of them can lead to eventual regrets. There is the selection we make when we look through the viewfinder at the subject; and there is the one we make after the films have been developed and printed. After developing and printing, you must go about separating the pictures which, though they are all right, aren’t the strongest.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson also shares why it is important to learn from our failures:

When it’s too late, then you know with a terrible clarity exactly where you failed; and at this point, you often recall the telltale feeling you had while you were actually making the pictures.

Was it a feeling of hesitation due to uncertainty? Was it because of some physical gulf between yourself and the unfolding event? Was it simply that you did not take into account a certain detail in relation to the whole setup? Or was it (and this is more frequent) that your glance became vague, your eye wandered off?

Mastery of Composition

Cartier-Bresson believed that a composition should serve to highlight the subject and anything that may distract the viewer should be eliminated from the frame.

If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Though his photographs may appear to be spontaneous, in reality, his compositions are highly calculated. To achieve this he used a number of techniques from art including the Golden Ratio (also known as the Golden Rule).

Cartier-Bresson says that while we should always think about composition when it comes to the actual shooting of the image, the photographer should always use intuition. Cartier-Bresson shoots what feels right, not what conforms to compositional rules.

Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move.

The Secret to Great Composition: Geometry

When Charlie Rose interviewed Cartier-Bresson, he asked him, “What makes a great composition?” Cartier-Bresson simply replied, “Geometry.”

My passion has never been for photography ”in itself,“ but for the possibility – through forgetting yourself – of recording in a fraction of a second the emotion of the subject, and the beauty of the form; that is, a geometry awakened by what’s offered. The photographic shot is one of my sketch pads.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

If you look at any of his images, you’ll notice whenever possible he makes use of geometric lines and shapes (triangles, circles, and squares) using them as frames within frames or to draw the viewer into the image.

In order to “give a meaning” to the world, one has to feel oneself involved in what one frames through the viewfinder. This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry – it is by great economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression. One must always take photographs with the greatest respect for the subject and for oneself.

The Golden Ratio

So what compositional tools did Cartier-Bresson use? He mainly used a technique called the Golden Ratio, also known as the Golden Rule.

Not only did he use it when framing his shot, but he also used it when analyzing his images during the editing stage.

In applying the Golden Rule, the only pair of compasses at the photographer’s disposal is his own pair of eyes. Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed – and then it can be used only for a post-mortem examination of the picture.

I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Now you might be asking yourself what is the “Golden Rule”? To answer that fully it would take another article, but here’s a quick summary:

The golden ratio, also known as Phi, is a mathematical tool used to achieve visual harmony and balance in a composition. To many, it’s the most pleasing way of arranging lines and shapes in a composition.

This technique was used by some of the greatest artists of all time, and the calculation has been found in their most famous works. Leonardo da Vinci was an artist who used the golden ratio technique extensively.

Like the rule of thirds, this mathematical concept can be applied to photography to make images more visually appealing to the viewer.

Cropping

Cartier-Bresson is one of the original purists that insisted on never cropping his images and printing the whole negative.

He believed that whenever you took a photo, it should always be composed in the viewfinder. If he wasn’t happy with the framing or composition, he would disregard the image.

If you start cutting or cropping a good photograph, it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions. Besides, it very rarely happens that a photograph which was feebly composed can be saved by reconstruction of its composition under the darkroom’s enlarger; the integrity of vision is no longer there.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

The photographer, Eve Arnold, an old friend and colleague at Magnum, maintains that Cartier–Bresson would crop his photographs if it made a better image. This was the case with Behind Gare St. Lazar, which is one of only a few images that he allowed to be cropped.

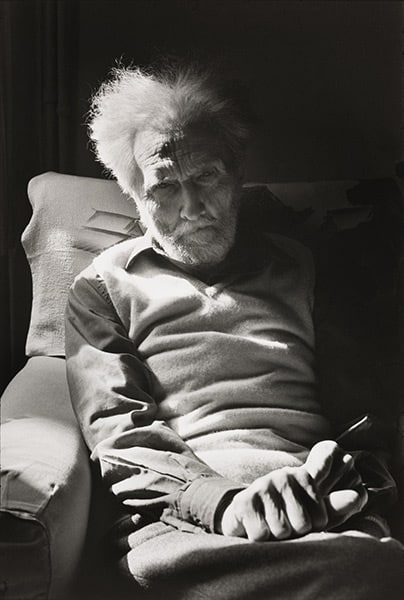

Portrait Lessons

Although Henri Cartier-Bresson is famous for his candid style of photography, he did also take a number of portraits in his career.

He always preferred to take his sitters’ portrait at home. When asked how long the session would take, he liked to answer, “Longer than the dentist but shorter than the psychoanalyst.”

If the photographer is to have a chance of achieving a true reflection of a person’s world – which is as much outside him as inside him – it is necessary that the subject of the portrait should be in a situation normal to him.

We must respect the atmosphere which surrounds the human being, and integrate into the portrait the individual’s habitat – for man, no less than animals, has his habitat.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Another important portrait lesson is to remain unobtrusive, so the subject forgets about the camera. He also recommends not using any flashy equipment, which can intimidate the subject:

Above all, the sitter must be made to forget about the camera and the photographer who is handling it. Complicated equipment and light reflectors and various other items of hardware are enough, to my mind, to prevent the birdie from coming out.

Get to Know Your Subject

Next, Cartier-Bresson provides an insight into capturing the emotion of the human face and the importance of getting to know your subject.

What is there more fugitive and transitory than the expression on a human face? The first impression given by a particular face is often the right one; but the photographer should try always to substantiate the first impression by ”living“ with the person concerned.

Usually, when taking a portrait, I feel like putting a few questions just to get the reaction of a person. It’s difficult to talk at the same time that you observe with intensity the face of somebody. But still, you must establish a contact of some sort.

Whereas with Ezra Pound, I stood in front of him for maybe an hour and a half in utter silence. We were looking at each other in the eye. He was rubbing his fingers. I took maybe altogether one good photograph, four other possible, and two which were not interesting. That makes about six pictures in an hour and a half. And no embarrassment on either side.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson explains why it’s difficult to take portraits for customers and finding the right balance.

The decisive moment and psychology, no less than camera position, are the principal factors in the making of a good portrait.

It seems to me it would be pretty difficult to be a portrait photographer for customers who order and pay since, apart from a Maecenas or two, they want to be flattered, and the result is no longer real.

The sitter is suspicious of the objectivity of the camera, while the photographer is after an acute psychological study of the sitter.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Finally, he says that a portrait is not only a reflection of the sitter but also the photographer.

It is true, too, that a certain identity is manifest in all the portraits taken by one photographer. The photographer is searching for identity of his sitter, and also trying to fulfil an expression of himself. The true portrait emphasizes neither the suave nor the grotesque, but reflects the personality.

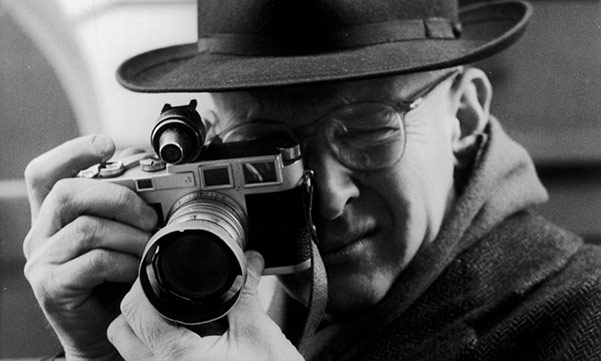

What Camera Did Henri Cartier-Bresson Use?

Leica M3 and 50mm Leica Summicron

This was Cartier-Bresson’s setup for most of his life. For landscapes, he also used a wide-angle and telephoto lens.

I think with the 50 mm you can cover a large number of things. Sometimes, especially for landscape, you need a 90 mm because it cuts all the foreground which is not that interesting. But this you don’t decide beforehand… I’m going to work with such a lens… no.

It depends on the subject. The subject guides you, it’s there. Your frame, you see it, it’s a recognition of a certain geometrical order, as well as of the subject.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

He started with a Leica II and III with Elmar 50mm before making the switch. He also used a Zeiss Sonnar 50mm at times.

We don’t need very big equipment. Practically I work all the time with a 50 mm, a very wide open lens because I never know if I’m going to be in a dark room taking a picture in this moment and outside in full bright sun the next moment.

Film and Sharpness

Cartier-Bresson didn’t believe in using flash and he famously covered his camera’s body in black tape to make it less conspicuous. The 35mm Leica camera allowed him to photograph without attracting attention.

Cartier-Bresson worked exclusively with black and white film. He never took to color film, despite a few brave attempts in the late ’50s when working on an assignment at the magazine’s request.

Here’s what he had to say on why we shouldn’t concern ourselves with the sharpness of an image (or lenses for that matter).

I am constantly amused by the notion that some people have about photographic technique – a notion which reveals itself in an insatiable craving for sharpness of images.

Is this the passion of an obsession? Or do these people hope, by this trompe l’oeil technique, to get to closer grips with reality? In either case, they are just as far away from the real problem as those of that other generation which used to endow all its photographic anecdotes with an intentional unsharpness such as it was deemed to be ”artistic.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Other Cartier-Bresson Resources

Recommended Henri Cartier-Bresson Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: The man, the image and the world

- The Decisive Moment

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: Scrapbook

- The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers

Henri Cartier-Bresson Videos

Pen, Brush and Camera

Interview with Charlie Rose (2002)

Henri Cartier Bresson – Just Plain Love Documentary

Henri Cartier-Bresson Photos

Two men staring at the wall, Brussels 1932 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Rue Mouffetard, Paris 1954 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Munster, County Kerry, Ireland, 1952 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

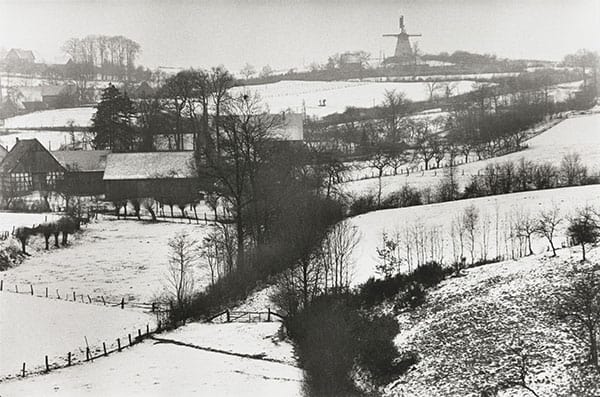

France, near the Belgian Border 1967 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

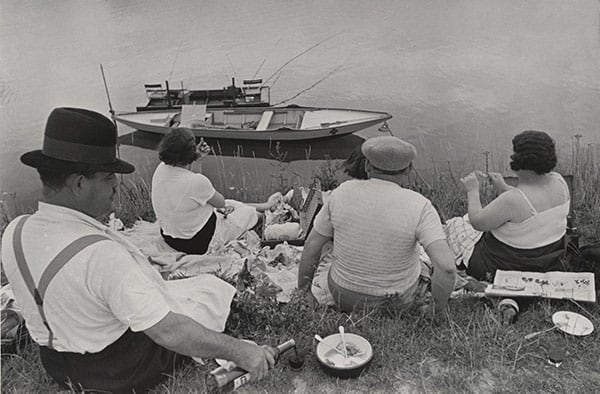

Juvisy, France 1938 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

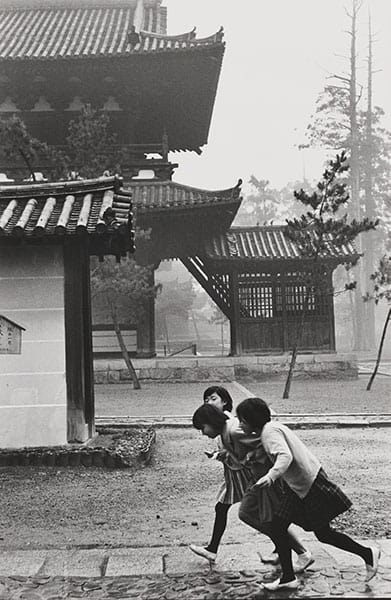

Kyoto, Japan 1965 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Madrid 1933 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Looking for more Henri Cartier-Bresson photos? Check out the Cartier-Bresson galleries at MoMA and Magnum Photos.

Recommended Reading

Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation

My Time with Cartier-Bresson, Ishu Patel

Interview with Shiela Turner-Seed, Aperture

Fact Check

With each Photographer profile post, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through Twitter or any other social media channel.

This article took 3 weeks to research and write. Sharing the link takes less than 2 minutes and doesn’t cost you anything.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Sources

Interviews and Conversations, 1951–1998

Interview with Shiela Turner-Seed, Aperture, 1973

Henri Cartier-Bresson Obituary, The Times, 2004

My Time with Cartier-Bresson, Ishu Patel, 2008

Living and Looking, New York Times, 2013

Henri Cartier-Bresson profile, Museum of Modern Art

History of Magnum, Magnum Photos

Henri Cartier-Bresson profile, Magnum Photos

Famous Photographers Tell How: Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1958

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Just Plain Love

Pen, Brush and Camera Documentary

Interview with Charlie Rose, 2002

India: Henri Cartier Bresson, 1988

Icons Of Photography The 20th Century, 1999

The Mind’s Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers, 2004

Henri Cartier Bresson: The man, the image and the world, 2006

Encyclopedia of Twentieth-century Photography, 2005

Henri Cartier Bresson: Scrapbook, 2006

The Decisive Moment, 1952 (2018 edition)

Henri Cartier-Bresson: A Biography, 2012

Masters of Photography, Aperture, 2015