Julia Margaret Cameron was one of the most important and innovative photographers of the nineteenth century.

Cameron’s work was controversial in her own time. Criticized for her so-called bad technique, she ignored convention and experimented with composition and focus.

Cameron is credited with creating the first photographic close-up portraits and influencing the use of diffused focus.

Her photographs of famous Victorians have been described as some of the finest portraits of the nineteenth century in any medium.

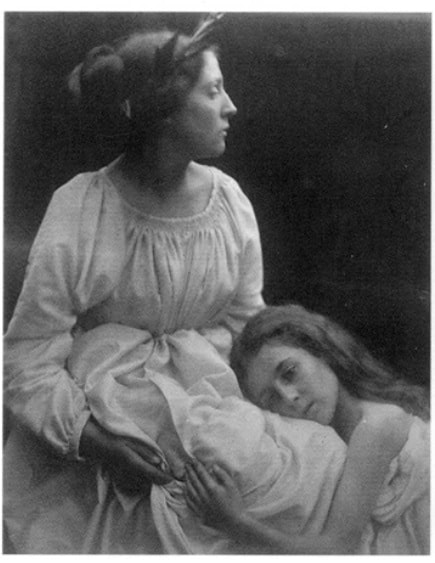

She was also one of the first photographers to produce staged photographs, posing her sitters – friends, family and house servants – as characters from literary, mythology, religion and history.

Cameron had a short but prolific career as a photographer. She took up the camera at age forty-eight and made over 1200 photographs over fourteen years.

She was one of the first photographers to realize how human emotion could be further emphasized through lighting effects, selective focus and framing.

Largely self-taught, she made photographs that were intended to transcend appearance and speak directly to the human spirit. Today she is celebrated as one of the pioneering portrait photographers.

In this article, we will aim to provide an introduction to Cameron’s work, with particular emphasis on her photography style and innovative working methods.

Related: 25 Timeless Julia Margaret Cameron Quotes to Bookmark

Editor note: If you enjoy our Julia Margaret Cameron profile, then we would be grateful if you could share it with others through your blog, website, forums or social media.

Table of Contents

About Julia Margaret Cameron

Name: Julia Margaret Cameron (born Pattle)

Nationality: British

Genre: Portrait, Conceptual, Fine Art

Born: 11 June 1815 – Calcutta, India

Died: 26 January 1879 (63 years) – Kalutara, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka)

Julia Margaret Cameron Biography

Julia Margaret Pattle was born in Calcutta, India, to James Pattle, an Englishman and his French wife, Thérèse l’Etang. At a young age, Julia and her six sisters were sent to Europe, spending most of their childhood with their grandmother in Paris and Versailles.

In 1936, while recovering from illness in South Africa, Julia Margaret met Charles Hay Cameron, an important figure in the British administration of India, and a man twenty years her senior. The couple married two years later in Calcutta.

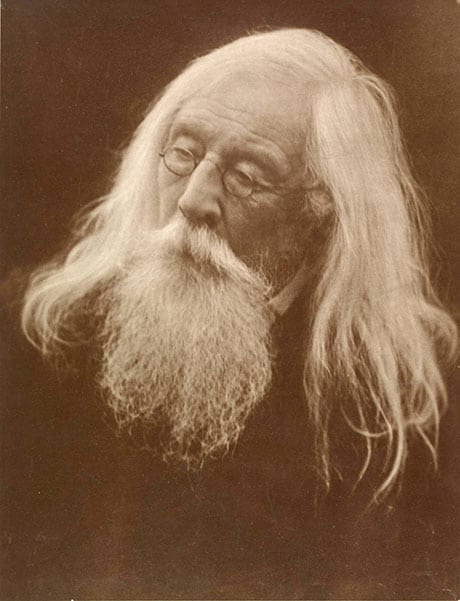

During the same stay, she met the astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel. He was probably the first person to introduce Cameron to photographic processes and is the subject of some of her best portraits. Herschel would become a life-long friend, mentor and supporter of her work.

Editor note: Sir John Herschel was the inventor of the cyanotype print and is credited as being the first person to use the word photography in 1839.

For the next ten years, the Cameron’s lived in India and were highly respected and active in colonial politics and society. Julia was kept busy running the home, looking after the children, and hosting social gatherings.

Moving to England

In 1848, Charles retired, and the Cameron’s moved to London. Several of the Pattle sisters had married and settled in London and the Camerons’ two eldest children, were sent to England to be educated.

Julia’s sister, Sarah Prinsep, had a house in Kensington and was visited regularly by some of the most important literary and artistic figures.

In 1860, the Cameron family purchased two cottages in Freshwater, a village on the Isle of Wight, located on the south coast of England, close to the estate of Alfred Lord Tennyson.

The Cameron’s named their new home Dimbola Lodge and it was here where Cameron began her photography journey.

During this period, Freshwater became something of a focal point for artists, writers, and intellectuals, who gathered at the Tennyson and the Cameron residencies.

Dimbola was ideally located ten minutes up from Freshwater Bay and half a mile from Farringford, the home of the Tennyson family.

Freshwater in the 1860s and 1870s was unique, for not only was it an enchanting place in itself with high downs, glorious views of the English Channel and air “worth sixpence a pint” as Tennyson wrote to a friend, but a delightful company of people had come to live there to be near their friend Tennyson.

Anne Thackery

This area on the west side of the Island, known for its celebrity circle, has since been named, “The Tennyson Mile.”

Photography Journey

In December 1863, when Charles was away in Ceylon, visiting the family’s coffee plantations, Cameron, who by now was forty-eight, was given a camera by her eldest daughter Julia, “It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.”

There is evidence that Cameron had taken a few photographs before this or at least experimented with printing negatives. She wrote to Herschel and said that the painter David Wilkie Wynfield, who took a series of photos of his fellow painters in fancy dress in the early 1860s, had given her a lesson.

It also seems likely that her daughter wouldn’t have given her a cumbersome 11″×9″ camera, with accompanying chemicals and accessories, unless she had shown some interest in the subject.

Cameron herself dated the start of her photography work from the acquisition of the camera.

Early Experiments

Setting up a darkroom in the coal store and converting an old glass-enclosed chicken house to a studio, Julia set about experimenting with the medium. She described her first days working in photography as a process of trial and error:

Many and many a week in the year 1864, I worked fruitlessly, but not hopelessly… I began with no knowledge of the art. I did not know where to place my dark box, how to focus my sitter, and my first picture I effaced to my consternation by rubbing my hand over the filmy side of the glass.

Julia Margaret Cameron – Annals of My Glass House

Cameron worked tirelessly to understand and master the steps needed to produce negatives with wet collodion on glass plates. In a letter to Sir John Herschel in 1864, she described her initial struggle:

At the beginning of this year, I took up photography, and set to work alone and unassisted. I felt my way literally in the dark through endless failures, and last came endless successes!

Her first success came in 1864, with a portrait of Annie Philpot, the daughter of her neighbor.

During this time, she was supported by her long-suffering family, which she writes about in her book:

Personal sympathy has helped me on very much. My husband from first to last has watched every picture with delight, and it is my daily habit to run to him with every glass upon which a fresh glory is newly stamped, and to listen to his enthusiastic applause. This habit of running into the dining-room with my wet pictures has stained such an immense quantity of table linen with nitrate of silver, indelible stains, that I should have been banished from any less indulgent household…

Photography Career

Cameron may have begun as an amateur, with no interest in earning money from her new hobby, but that soon changed and she quickly adopted a professional approach to her work by copyrighting, exhibiting, and selling prints.

Within 18 months she had sold photographs to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), set up a second studio inside the family home, and arranged for a London based firm to publish and sell her prints.

That being said, Cameron had no interest in pursuing a career as a commercial portrait photographer. She was more interested in experimentation and photography as art. Cameron practiced photography on her own terms.

With the help of friends, family members, and her household staff, Cameron used photography as a means of illustrating a mixture of historical, artistic and literary themes.

For one of her tableau’s, a housemaid might be transformed into a Madonna, or her husband with his bushy grey beard into Merlin, or her neighbor’s young child into an angel.

The two main sources of her work were the allegorical teachings from the bible and early renaissance art.

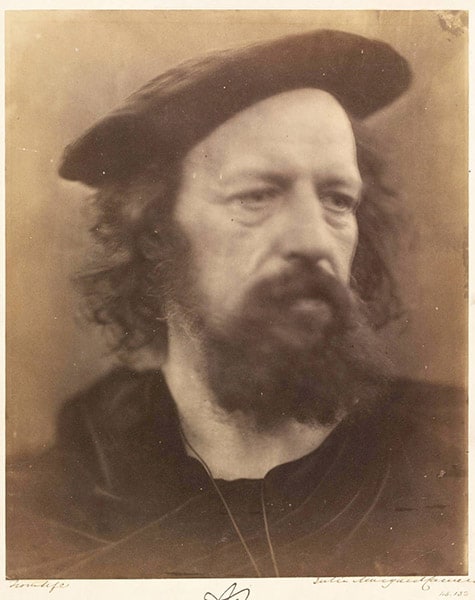

Cameron also took portrait photographs of Victorian celebrities, many of whom were close family friends, including Charles Darwin, Alfred Tennyson, and John Herschel.

Critics and Awards

Like many people ahead of their time, Cameron had her fair share of critics. The photographic establishment found fault with her supposedly poor technique: leaving smudges, printing from cracked negatives and her “out of focus” effects.

Yet, she received several awards from overseas, including a gold medal at Berlin in 1866, as well as honorable mentions at international exhibitions. Her photography was also greatly admired by artists – a view which is shared by art critics today, who praise her for putting beauty before technical perfection.

In October 1875, at the height of her fame, Julia Margaret and her husband left Freshwater and moved to their plantations in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Despite taking her cameras with her, she rarely practiced photography due to the shortage of materials and the lack of suitable subjects. In 1879, Cameron died in Ceylon after a brief illness at the age of 63.

Legacy

In 1868, the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) provided Cameron with the use of two rooms to exhibit her photographs, effectively making her the museum’s first artist in residence.

In a career that lasted just over 11 years, Julia Margaret Cameron made just over 1200 photographs. The Royal Photographic Society owns around 800 of these, along with a hand-written manuscript of Cameron’s unfinished autobiography, Annals of my Glasshouse.

Cameron’s photographs are held in collections of some of the best art museums in America and Europe. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York exhibited her work in 2013.

Her great-niece, the famous writer Virginia Woolf (her mother was Julia Jackson, the subject of some of Cameron’s most arresting portraits) wrote a play about her, titled Freshwater.

To preserve Cameron’s legacy, the Julia Margaret Cameron trust was set up, along with a museum at Dimbola Lodge on the Isle of Wight. The museum provides historical information on her life and works. If you’re ever on the Isle of Wight, then I recommend visiting.

Julia Margaret Cameron’s Style

- Soft-focus, dreamy

- Close-up, posed

- Experimental, embraced imperfections

- Staged, theatrical

- Narrative, allegorical

- Spiritual, contemplative

- Mysterious, ambiguous

Julia Margaret Cameron’s Working Methods

Because photography as a practice was still in its infancy, Cameron wasn’t bound by convention and was free to make her own rules. The type of images being made by other photographers at the time didn’t interest Cameron.

My first successes in my out-of-focus pictures were a fluke. That is to say, that when focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.

Julia Margaret Cameron

Cameron was interested in capturing another kind of photographic truth. Not one dependent on the accuracy of sharp detail, but one that conveyed the spirit and emotional state of her sitter.

Cameron’s exposures were long (often around 5 minutes). Unlike other photographers, she didn’t use any clamps or props, which meant that her sitters had to sit still for a long time. As this was difficult to do, her images sometimes came out soft and out of focus.

I counted four hundred and five hundred and got one good picture. Poor Wilfrid said it was torture to sit so long, that he was a martyr! I bid him be still and be thankful. I said, I am the martyr. Just try the taking instead of the sitting!

Julia Margaret Cameron

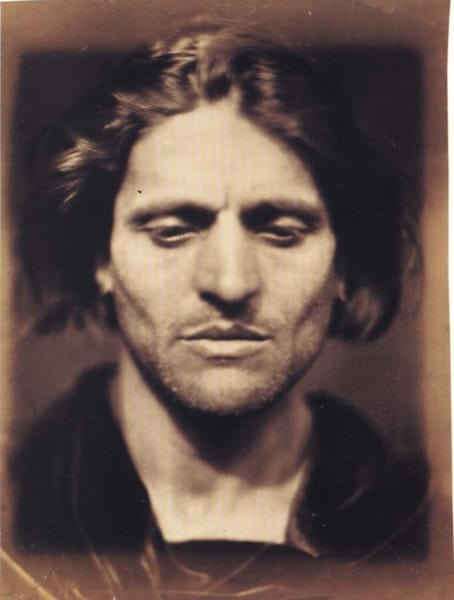

Portraits

Looking at Cameron’s portraits of men, two things about them are apparent. First, the majority show only the subject’s head and shoulders, with the torso often draped in dark cloth. This makes these photos potentially the first “close-ups” in photographic history. Secondly, she would often light just one side of the face, making the close-up effect even more dramatic and revealing.

When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer.

Julia Margaret Cameron

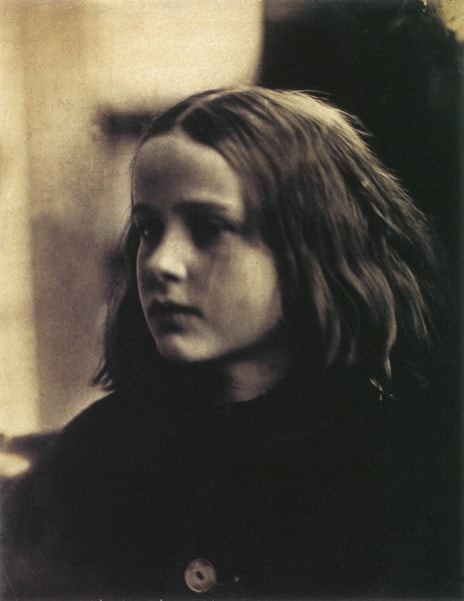

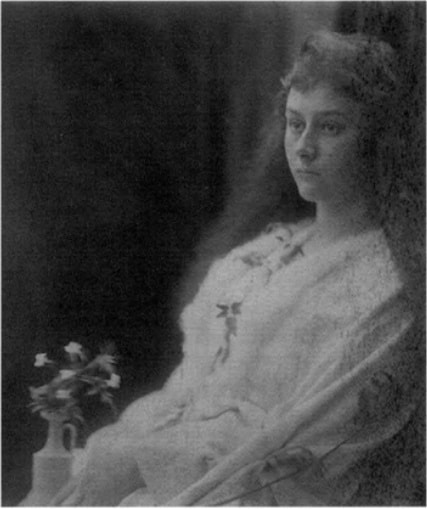

Cameron took a different approach when photographing women. She framed her subjects at a more traditional distance and threw light onto her sitter from every possible angle, giving her images a softer and more flattering effect.

She was interested in conveying their natural beauty and often asked female sitters to let down their hair, so she could photograph them as they were and not how they had been accustomed to presenting themselves.

Fancy Subjects for Pictorial Effect

In addition to making portraits both of male and female subjects, Cameron was also one of the first photographers to create narrative-driven photographs or as she liked to call them “fancy subjects for pictorial effect.”

My aspirations are to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real and ideal and sacrificing nothing of the truth by all possible devotion to poetry and beauty.

Ahead of the time again. Cameron’s pictures, in which her sitters posed as figures from history and literature were taken over a century before the likes of Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson began staging photos.

Cameron looked to painting and sculpture as inspiration for her allegorical and narrative subjects. She was also interested in religion, literature and poetry and produced photographic illustrations for Tennyson’s Idylls of the King at his request.

Cameron was not obsessed with conveying narrative fact, or realistic illustrations of religious subjects, but rather wanted to suggest themes that would could be left open to interpretation. Her tableaus have a sense of mystery about them and force the viewer to complete the picture. To me, this is what makes her work so timeless.

A photographer, like all artists, is at liberty to employ what means he thinks necessary to carry out his ideas. If a picture cannot be produced by one negative, let him have two or ten; but let it be clearly understood, that these are only means to an end, and that the picture when finished must stand or fall by the effects produced, and not by the means employed.

Julia Margaret Cameron

The Technical Side

Cameron was not the best of technicians. She often included imperfections in her prints – swirls, streaks and even fingerprints – that many photographers would have rejected as technical flaws. Although she was criticized in his life, these imperfections are now praised for being ahead of their time.

When Cameron took up photography, it involved hard physical work and the use of potentially hazardous chemicals. The wooden camera she used, which sat on a tripod, was extremely large and cumbersome. To make her photos, she used the most common practice at the time, which was albumen prints from wet collodion glass plate negatives.

Here’s a brilliant video from the Victoria and Albert museum which explains the wet collodion process in more detail. After finishing this article, we recommend visiting the V&A website as they have a section dedicated to the work of Julia Margaret Cameron.

Other Julia Margaret Cameron Resources

Recommended Julia Margaret Cameron Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

Julia Margaret Cameron Videos

Meet the Photographer (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Julia Margaret Cameron’s Working Methods

Julia Margaret Cameron Photos

The Kiss of Peace, Elizabeth Keown, Mary Hillier, 1870 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Enid, Alice Liddell, 1872 © Victoria and Albert Museum

I Wait, Cameron’s niece Rachel Gurney © Victoria and Albert Museum

So like a shatter’d Column lay the King, (Illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and other poems), 1875 © Victoria and Albert Museum

lago study from an Italian, Angelo Colarossi, 1867 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Charles Hay Cameron 1871 © Victoria and Albert Museum

The Dream, 1869 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Pomona, Alice Liddell, the inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1872 © Victoria and Albert Museum

View more Julia Margaret Cameron Photos at the Victoria and Albert Museum website.

Fact Check

With every article, we try to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about the life and work of Julia Margaret Cameron’s then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve found our Julia Margaret Cameron article helpful, then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share it with other photographers. The article took several days to research and write, sharing takes less than a minute. Thanks for your support.

Related Articles

Portrait Photography Quotes

Quote Series: What Makes a Good Photograph

Richard Avedon: The Million Dollar Man

Sources

Museum of Modern Art, Julia Margaret Cameron Biography

Victoria and Albert Museum, Julia Margaret Cameron Collection

Julia Margaret Cameron: A Critical Biography, Colin Ford, 2003

In Focus: Julia Margaret Cameron: Photographs from the Getty Museum, 1996

Julia Margaret Cameron by Marta Weiss, 2015

Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, 2008

Julia Margaret Cameron The Complete Photographs by Julian Cox

The Art Story, Julia Margaret Cameron Profile

Dimbola Lodge, Julia Margaret Cameron Biography