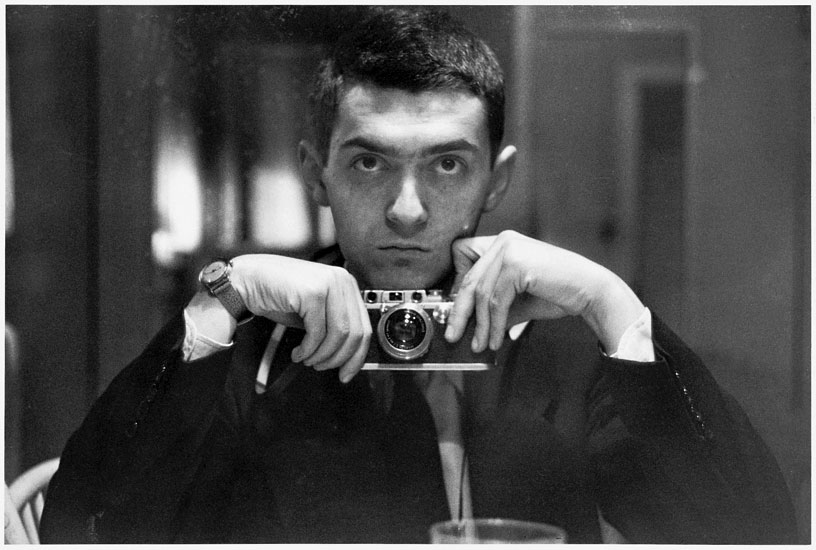

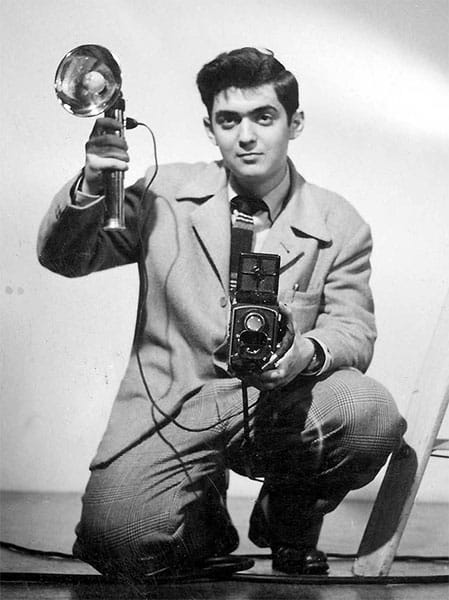

Before becoming the critically acclaimed filmmaker responsible for iconic films such as 2001: Space Odyssey, Clockwork Orange, and The Shining, Stanley Kubrick spent five years working as a photographer for Look magazine.

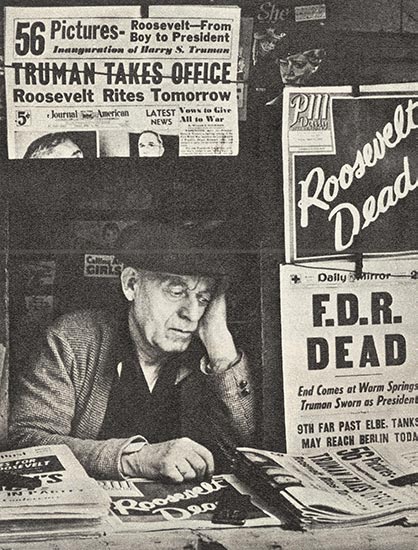

In June 1945, sixteen-year-old Stanley Kubrick published his first photograph. The photograph shows a depressed newspaper vendor framed by broadsheets and the headline announcing the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Between 1945 and 1950, the Bronx native took over 13,000 photographs for the magazine, nine hundred of which were published. During his time at Look, he progressed from apprentice to staff photographer in six months. He was the youngest photographer in the magazine’s history at just seventeen years old.

The best photographers – from Mary Ellen Mark to James Van Der Zee to Robert Capa – are artists who function both as directors and cutters: each shot is basically an entire movie tailored into a single frame. Kubrick is first and foremost a photographer, like them, and almost any still from his monochromatic movies tells a complete story.

Elvis Mitchell, Curator, Film Independent at LACMA

This is quite a long article, so make yourself a drink or grab a beer and sit back and enjoy the read. If you don’t have time to read the full article now (around 20 minutes), then bookmark the page and read it a section at a time. Alternatively, feel free to use the table of contents, to skip ahead to whatever section interests you.

Related: 25 Stanley Kubrick Quotes for Photographers

If you enjoy reading the article, then I would be grateful if you could share it, so other photographers and filmmakers like you can also benefit from the article.

Table of Contents

Kubrick’s Photography Career

Starting Out

Kubrick’s father, a professional physician and amateur photographer introduced his son to photography at an early age. When Stanley was thirteen, his father bought him his first camera, a Graflex Pacemaker Speed Graphic. Equipped with his new camera, a young Stanley would shoot baseball games, school activities, and his neighborhood streets.

Stanley shared a passion for photography with his neighbor Marvin Traub, who had a darkroom in his bedroom. When they weren’t in the darkroom, they would be out taking pictures and thinking up photo assignments for themselves. The photographer Weegee whose photos for PM Daily would provide an early and significant influence on the two youngsters.

Although he wasn’t aware of it at the time, Kubrick started building toward his life work as a filmmaker during his early high-school years. While still a senior – and not quite seventeen – he sold his first photograph to Look magazine.

His First Published Photo

The day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt died, while on his way to school, Stanley noticed a newsagent vendor on 170th street surrounded by headlines announcing the death of the president. He took a photo that changed his life.

Kubrick’s carefully framed photo captured the grief of the nation over the sudden death of the president. He later admitted privately to friends that he convinced the vendor to look more depressed than he was. This incident presages Kubrick’s method of working with actors on movie sets to get them to generate the right emotion for the shot.

By this time, he had his own darkroom at home. Instead of attending school that day, he developed his film and after seeing the negatives believed the image to be sellable. He took the image to the New York Daily News, then used the newspaper’s offer as leverage with Look. The magazine paid $25, which was $10 better than the newspaper.

Look used the picture as the final image in a series about the late president in the June 26, 1945 issue of the magazine. After his first photo was published in 1945, Kubrick worked as a freelance photographer for the magazine, whilst still attending high school.

From Apprentice to Staff Photographer

After graduating, Kubrick attended night courses at City College for a year, hoping to get a B average so he could transfer to a regular undergraduate course. At the same time, he continued to work for the magazine.

The picture editor at the time Helen O’Brien, said, “Stanley had the highest percentage of acceptances of any freelance photographer I’ve ever dealt with.” Seeing the potential in the young photographer, Look offered him a job as an apprentice photographer.

My parents wanted me to become a doctor, and I was supposed to go to medical school, but I was such a misfit in high school that when I graduated, I didn’t have the marks to get into college. But like almost everything else good that’s ever happened to me, by the sheerest stroke of luck, I had a very good friend at Look which gave me a job as a still photographer. After about six months, I was made a full-fledged staff photographer. My highest salary was $105 a week, but I did travel around the country, and I went to Europe and it was a great thing. I learned a lot about people and things.

Stanley Kubrick

First Assignments

Kubrick began his photography apprenticeship with Look in 1946. In his first couple of years on the job, Kubrick turned his camera on nightclubs, the street of New York, and sporting events. Capturing everyday life with a sophistication that belied his youthful years. Many of these themes would continue to inspire the filmmaker later in his creative life.

One of his first photo essays, A Short, Short in a Movie Balcony (April 1946), shows four candid photos of a young man making advances on the young woman sitting beside him in a cinema.

The photoshoot was set up – the cinema was closed – and the two subjects were Stanley’s friends. He took both of his friends aside separately to give them direction. He told the woman to let the man really have it. So, when he does get slapped in the face, both the slap and his shock reaction are real. Stanley already knew how to get what he wanted for the camera.

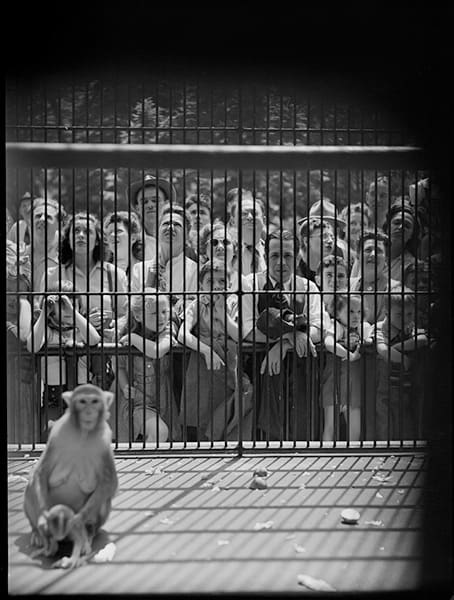

Another photo essay How People Look to the Monkeys (also in 1946) shows a monkey in a cage being watched by spectators. The monkey house had an indoor and outdoor area. While the monkeys were in the outdoor area, Kubrick stationed himself in the indoor area with his lens poking through the food slit so he could capture the monkeys with the spectators in the background. The caption cleverly reads: “A monkey watching people.”

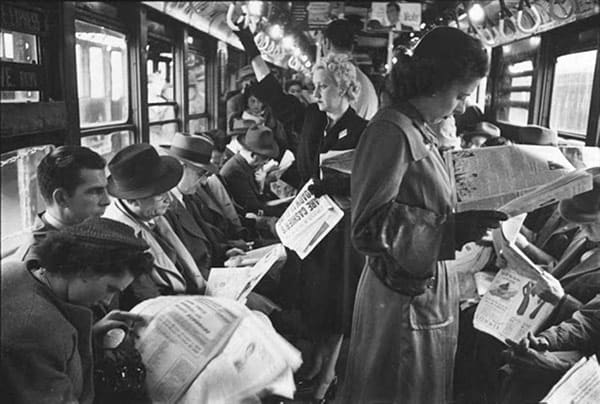

Candid Subway Photos

While Stanley displayed a talent for staged photos, suggesting a fondness for fiction, he also developed various candid photo techniques in keeping with the magazine’s journalistic nature.

For a photo essay titled, Life and Love on a New York Subway in March 1947, Kubrick hid a shutter release switch in his pocket with the cable running down the sleeve of his jacket to his camera, which was concealed in a bag with a hole.

Here is an explanation from Kubrick about how he took these photographs:

I wanted to retain the mood of the subway, so I used natural light. People who ride the subway late at night are less inhibited than those who ride by day. Couples make love openly; drunks sleep on the floor and other unusual activities take place late at night.

To make pictures in the off-guard manner he wanted to, Kubrick rode the subway for two weeks. Half of his riding was done between midnight and six a.m. Regardless of what he saw he couldn’t shoot until the car stopped in a station because of the motion and vibration of the moving train. Often, just as he was ready to shoot, someone walked in front of the camera, or his subject left the train.

Kubrick finally did get his pictures, and no one but a subway guard seemed to mind. The guard demanded to know what was going on. Kubrick told him.

“Have you got permission?” the guard asked. “I’m from LOOK,” Kubrick answered.

“Yeah, sonny,” was the guard’s reply, “and I’m the society editor of the Daily Worker.”

For this series, Kubrick used a Contax and took the pictures at 1/8 second. The lack of light tripled the time necessary for development.

Excerpt from Camera Quiz Kid: Stan Kubrick, The Camera, October 1948

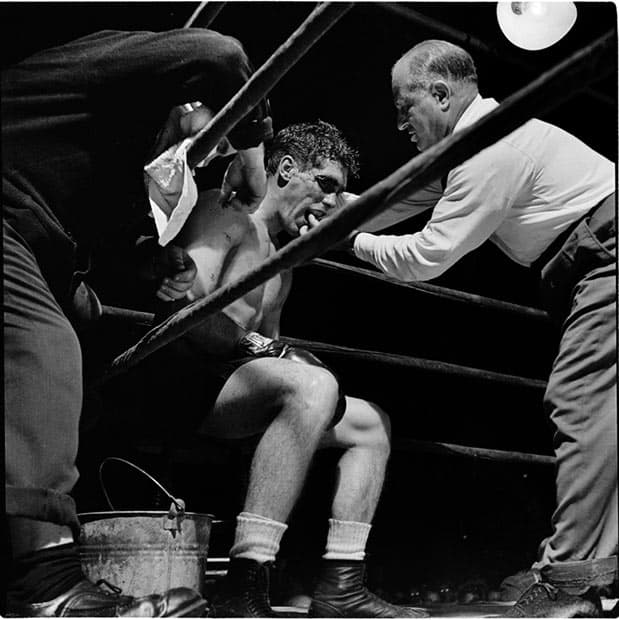

The Prizefighter

Towards the end of 1948, Kubrick was given another photo essay, this time on boxer Walter Cartier. For the story, the photographer followed Cartier between two fights, capturing him from the moment he woke up, right up to his fight.

The striking image that filled the entire first page of the seven-page sequence demonstrates how Kubrick had matured as a photographer.

Cartier sits on a bench, as he waits before his fight, with his gloved hands in his lap, leaning back against a cinder-block wall. The boxer gazes upward, with a single ceiling light casting part of his face in shadow. Shooting from his favored low angle, Kubrick makes Cartier look powerful, almost like a modern-day gladiator gathering strength before battle.

The photo story that followed is headed, The Day of the Fight and consisted of nineteen photos. The candid photos included Cartier repairing his nephew’s toy boat, hanging out at Staten Island beach and watching a ball game at Yankee stadium. The photo story closes with Cartier knocking out his opponent. The victorious Cartier is shown standing in the ring while his opponent lies on the canvas out for the count.

These photos were published with the title Prizefighter in the January 18, 1949 edition of the magazine. This was an ambitious essay for the young Kubrick and one that got his editor’s attention at Look.

Veteran Photographer

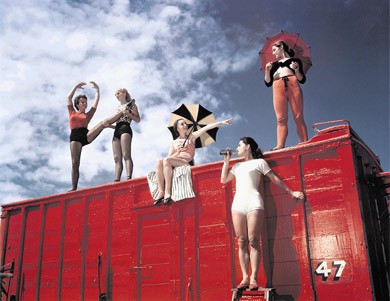

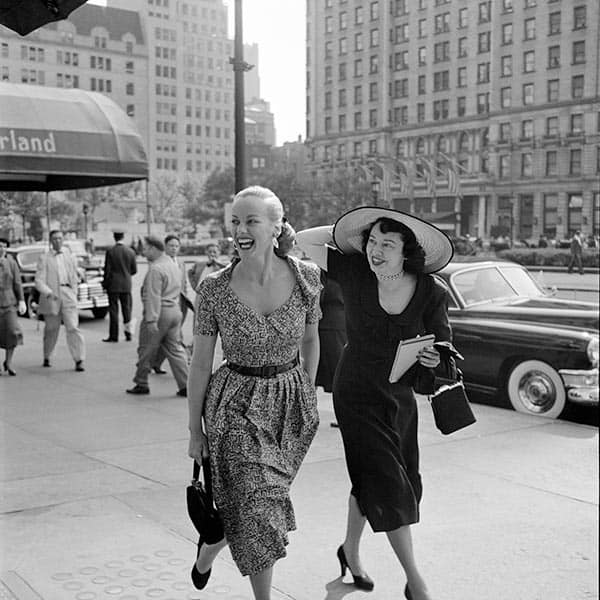

In 1949, Kubrick began working higher-profile assignments. By the end of the year, he had produced several character-centric photo essays about the lives of celebrities, showgirls, artists, athletes and the like.

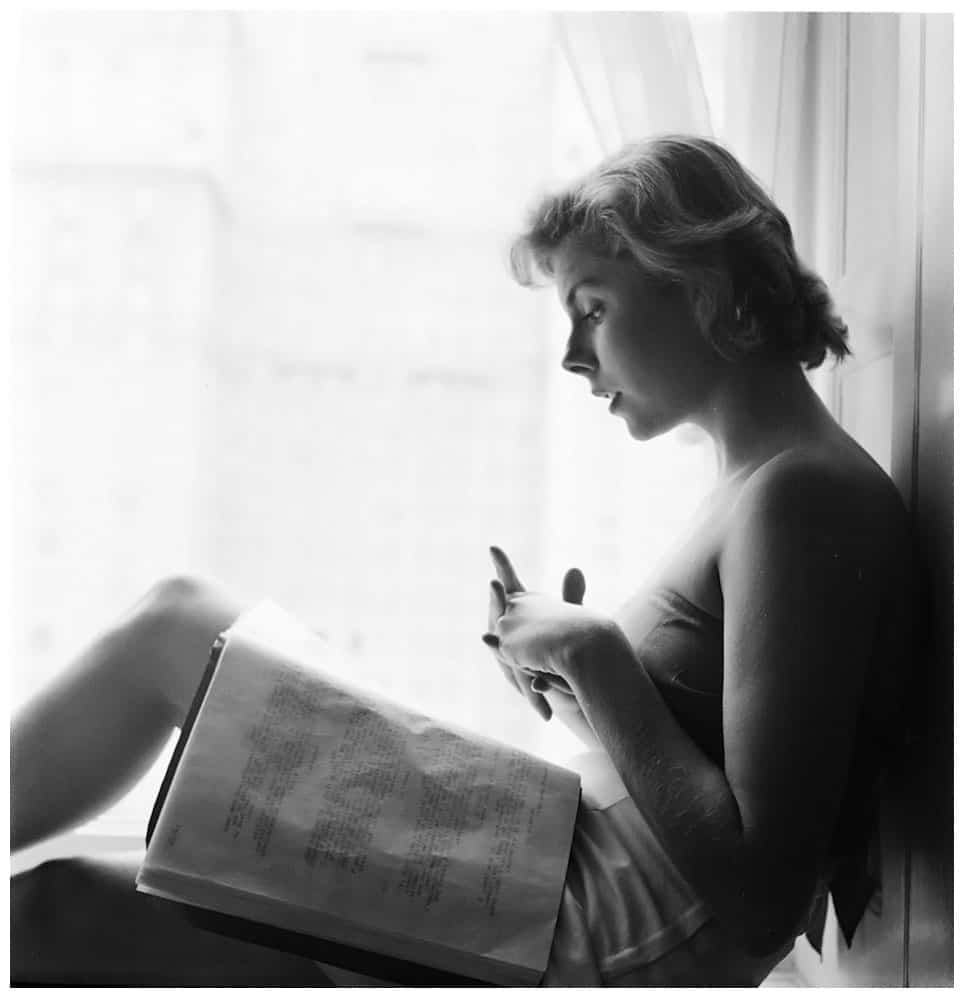

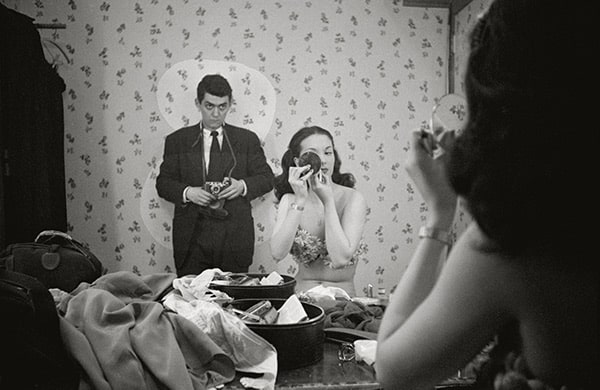

In August 1950, Kubrick did a profile on the Hollywood actress, Faye Emerson. As part of the photo series, he photographed Emerson on interviews, laughing with reporters, juggling phone calls at the office and doing her hair in front of the mirror.

Other subjects include Leonard Bernstein, Montgomery Clift, Frank Sinatra, President Eisenhower, and Rocky Graziano. He even journeyed to Europe on assignment and took travel photographs for the magazine.

It was tremendous fun for me at that age but eventually, it began to wear thin, especially since my ultimate ambition had always been to make movies. The subject matter of my Look assignments was generally pretty dumb. I would do stories like: “Is an Athlete Stronger Than a Baby?”, photographing a college football player emulating the ‘cute’ positions an 18-month-old child would get into. Occasionally, I had a chance to do an interesting personality story. One of these was about Montgomery Clift, who was at the start of his brilliant career. Photography certainly gave me the first step up to movies. To make a film entirely by yourself, which initially I did, you may not have to know very much about anything else, but you must know about photography.

Stanley Kubrick

Learning from Experience

His short time as a photographer with Look taught a young Stanley the importance of story and how to form a narrative with his images. He also learned to work and collaborate with colleagues, whether writers, picture editors or managing editors to create concise features. These experiences along with learning how to light and understanding composition laid the foundations for his move to motion pictures.

I was at Look for four years until the age of 21. And of course, that would have been the period I’d have spent in college, and I think that what I learned and the practical experience, in every respect, including photography, in that four-year period exceeded what I could have learned in school.

Stanley Kubrick

Below is a video about Kubrick’s work as a photographer for Look.

Transitioning to Cinema

By 1950, Kubrick was ready to start the next chapter in his career and put all his savings into his first film project.

Day of the Fight

The director made the boxer Walter Cartier, the subject of his film, revisiting and improving on the photos published for Look in 1949. Like the photo essay, the 16-minute documentary short follows the boxer and his routine leading up to a big fight. Kubrick used his photos from Look to storyboard and work out framing and lighting for the documentary film.

The director took care of everything: subject, script, locations, photography, sound, and editing. The commentary was written by Robert Rein and read by Douglas Edwards. In one sequence the Cartier brothers walk towards us, and the camera moves backward. The reverse tracking shot is one of Kubrick’s most recognizable camera movements and is used in all his movies.

The Final Sequence

The film’s final sequence, a boxing match, the sound of which was recorded live, was shot using two 35mm Eyemo spring-loaded cameras (at the time used by war cameramen) loaded with 100ft of black-and-white film.

Kubrick operated a camera handheld on one side of the ring, whilst his friend, Alexander Singer stood on the other side, with his camera propped on a tripod. Both men were shooting 100ft reels of film, which required constant reloading. With two cameras, one camera could be shooting footage whilst the other was reloading film. If you watch the film, you can see Kubrick reloading his camera on the other side of the ring when Cartier knocks out his opponent.

The quality isn’t the best, but it’s still an interesting watch to see how the great filmmaker started on his journey. It’s been mentioned by a few people that Raging Bull may have been influenced by the film, whether that’s true or not, you’ll have to ask Scorsese. It’s also worth comparing the photo essay Kubrick did for Look with the film.

I’d had my job with Look since I was seventeen, and I’d always been interested in films, but it never actually occurred to me to make a film on my own until I had a talk with a friend from high school, Alex Singer, who wanted to be a director himself (and has subsequently become one) and had plans for a film version of the Iliad.

Alex was working as an office boy for The March of Time in those days, and he told me they spent forty thousand dollars making a one-reel documentary. A bit of simple calculation indicated that I could make a one-reel documentary for about fifteen hundred. That’s what gave me the financial confidence to make Day of the Fight.

I was rather optimistic about expenses; the film cost me thirty-nine hundred. I sold it to RKO-Pathe for four thousand dollars, a hundred-dollar profit. They told me that was the most they’d ever paid for a short. I then discovered that The March of Time itself was going out of business.

Stanley Kubrick

Becoming a Full-Time Filmmaker

Several months after The Day of the Fight (1950), Kubrick quit his job at Look to devote himself to filmmaking full-time. Kubrick’s time at Look allowed him to develop his talent for storytelling and hone his visual style. Looking at his photos today, you can see how Kubrick started to explore themes and imagery that he would later visit in his films.

Kubrick followed The Day of the Fight with two more short films: Flying Padre (1951) and The Seafarers (1953).

After I quit Look in 1950, I took a crack at films and made two documentaries, Day of the Fight, about prizefighter Walter Cartier, and The Flying Padre, a silly thing about a priest in the Southwest who flew to his isolated parishes in a small airplane. I did all the work on those two films, and all the work on my first two feature films, Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss. I was cameraman, director, editor, assistant editor, sound effects man – you name it, I did it. And it was invaluable experience, because being forced to do everything myself I gained a sound and comprehensive grasp of all the technical aspects of filmmaking.

He launched his legendary feature film career with his first narrative feature, the war film Fear and Desire (1953) and finished it with Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

Kubrick’s Photography in Films

Probably no director in the history of cinema has involved themselves more deeply in the photographic process than Stanley Kubrick. The photography techniques he gained in the four years he worked for Look would play an important role throughout his career.

When a director dies, he becomes a photographer. Killer Kiss might prove that, when a director is born, a photographer doesn’t necessarily die.

Stanly Kubrick

If you want to see an example of Kubrick’s use of photography in his films, then watch Barry Lyndon (1975). In the film, Kubrick assembles perhaps the most beautiful sets of images ever printed on a single strip of celluloid. Each composition is like a painting and they link together like a wondrous mosaic. None of these images would have been possible if it wasn’t for Kubrick’s mastery of camera, composition and lighting.

Here’s what Martin Scorsese said about the film:

I’m not sure if I can say that I have a favorite Kubrick picture, but somehow, I keep coming back to Barry Lyndon. I think that’s because it’s such a profoundly emotional experience. The emotion is conveyed through the movement of the camera, the slowness of the pace, the way the characters move in relation to their surroundings. People didn’t get it when it came out. Many still don’t. Basically, in one exquisitely beautiful image after another, you’re watching the progress of a man as he moves from the purest innocence to the coldest sophistication, ending in absolute bitterness – and it’s all a matter of simple, elemental survival. It’s a terrifying film because all the candlelit beauty is nothing but a veil over the worst cruelty. But it’s real cruelty, the kind you see every day in polite society.

Martin Scorsese

Making Great Films

In his career, Kubrick directed just thirteen feature films, each one different from the others in both style and content. He has never made the same type of film twice. With every film, he starts over again.

Although Kubrick made fewer films than most filmmakers, the ones he did make rank highly on the lists of the greatest films of all-time with 2001: Space Odyssey topping many of them.

He just felt strongly that enough films are being made, he didn’t want to add to the pile of ‘just okay’ movies. That’s why it took him so very long to decide, to plan and prepare, to film and to edit. Fast he was not – neither was Vermeer – and then there were the films he prepared and abandoned.

You know so well how easy it is to make a film. To make a good film is a different matter, and a good film that enough people want to see is rather difficult. A great film is almost a miracle – like any great work of art, great painting, novel, symphony or building. And I dare to define greatness by the test of whether the work lasts and serves as a reference for future generations in order to have a look at our time.

Jan Harlan, The right-hand man, BFI Interview

Stanley Kubrick didn’t just create films; he created entire worlds on film. Due to his incredible use of photography and understanding of storytelling, his motion pictures remain timeless and get better with every viewing.

Kubrick’s Last Days

In March 1999, just five days after screening the final cut of Eyes Wide Shut to Warner Brother executives and his two stars: Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, Stanley Kubrick sadly passed away at the age of 70.

In an interview from 1968, Charlie Kohler asked Kubrick: You once said that if you hadn’t been a photographer at Look Magazine, you probably never would have gotten into films. What did you mean by that?

Well, first of all I was terribly unaware of everything else that you had to know about filmmaking, other than Podovkin’s Film Technique, and photography. Since I had read Podovkin and was a photographer, what could prevent me from making a movie? I could load the camera, shoot and I would have a movie. If I hadn’t been a photographer, I would have lacked the one essential ingredient you have to have to put anything on film, which is photography. Even though the first couple of films were bad, they were well photographed, and they had a good look about them, which did impress people.

Stanley Kubrick

This fan-made short documentary covers Kubrick’s photography career and early film work. The narration is taken from an interview that Kubrick did with Jeremy Bernstein in 1966. The recording is rare and provides an interesting insight into the mind of Kubrick before making his masterpieces 2001: Space Odyssey and The Shining.

Kubrick’s Photography Style

In his first six months as an apprentice photographer for Look, Kubrick would have been mentored by the magazines more experienced photographers. One of these mentors was Arthur Rothstein. In a 1978 interview, Rothstein said, “The greatest satisfaction an older photographer can have in his work is helping younger photographers achieve something. I helped Kubrick in his early days when he was staff photographer at Look.”

Photo Essays

According to Rothstein’s book, Photojournalism there was a six-stage photo-essay production process at the magazine. Photographers would become involved in the third stage of the process when assigned a story by their picture editor. Although photographers could pitch ideas, they were typically assigned photo stories based on their ability and preferences.

For the fourth stage of the process, the photographer and writer would go out on location to get the photos for the story.

Before heading out on assignment the photographer would discuss the assignment with the editor and be given information about the subject including a shooting script.

Look believed that it was important for writers to work with photographers to ensure they had complete knowledge of the story. Writers were encouraged to think in visual terms, and when preparing the script were told to include any information about the subject or the setting that could help the photographer capture the story.

The magazine wanted photographers to produce photo essays and narrative sequences, as opposed to isolated expressive pictures. Departures from the script would often occur, which required photographers to be flexible.

This approach to shooting would stick with Kubrick throughout his film career. In later interviews, he has commented on the importance of “being able to adjust for the final moment” and take advantage of an opportunity, even if means exposing weaknesses in the script.

Getting Coverage

In Rothstein’s book, he also mentions the importance of shooting coverage. Look focussed more on the photographs than the actual stories, and staff photographers including Kubrick learned that it was important to shoot freely to get more coverage than needed, to give the magazine’s art department a wide range of choices for story layouts. Another invaluable lesson that Kubrick would later use in his filmmaking.

While the editors at Look often encouraged simple composition and the use of natural light, which was typical of photojournalism of the time, Kubrick would often imitate the style of the Hollywood film noirs he admired. While on assignments he would always try and add drama to the subject whenever he had a chance.

Real is good, interesting is better.

Stanley Kubrick

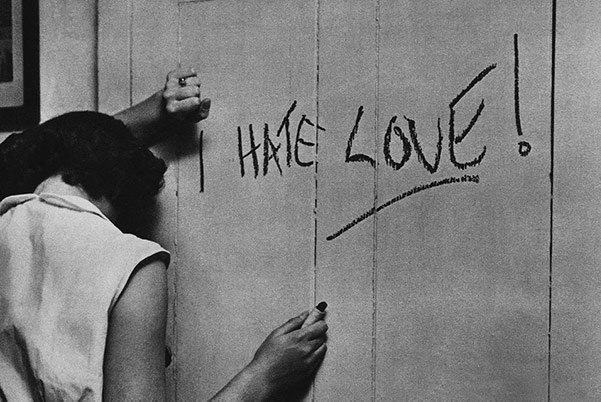

There are links between Kubrick’s photography work and his early filmmaking, with boxers and showgirls, which he photographed for the magazine, prominent in his first successful feature, Killer’s Kiss in 1955.

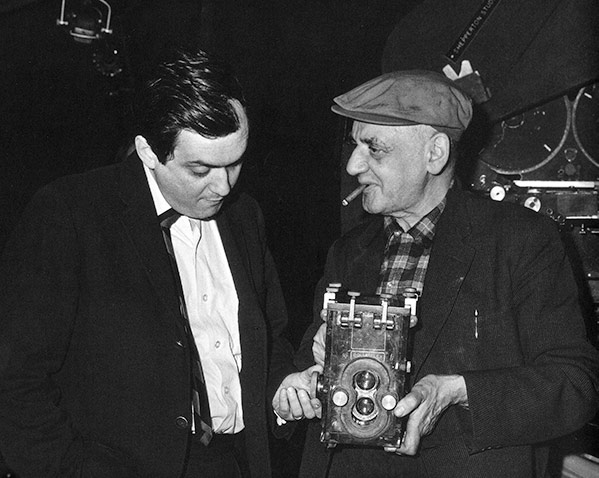

Kubrick and Weegee

The young Kubrick was an admirer of the tabloid photographer, Arthur Fellig, also known as Weegee, who would often catch New Yorker’s off-guard in his photo essays.

In his photo series, Life and love on the New York subway (March 1947), Kubrick would also catch his subjects unaware: a woman sleeping in her lovers arms, a woman nursing her baby, commuters passing time by reading the daily newspaper and a young man holding flowers above his head to prevent them from being crushed by fellow passengers.

In June 1947, Kubrick was sent by Look Magazine to photograph a behind the scenes look at the film The Naked City, which was inspired by Weegee’s 1945 photobook of the same name. They certainly met and knew each other. Kubrick’s early noir films Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956) have the same kind of look as Weegee’s gritty street style.

Kubrick later brought Weegee on as a set photographer for Dr. Strangelove (1964), despite the presence of two photographers already hired by the studio.

Peter Sellers has also credited Weegee as the direct inspiration for Dr. Strangelove’s voice. If you get a chance, then check out this Peter Seller’s interview where he talks about Weegee and coming up with the voice for the character.

Look Magazine

In the 40s and 50s, magazines were one of the major sources for news and entertainment. During this period, television was still in its infancy, so people read newspapers, listened to the radio, and would see newsreels at the movies to keep up to date with current affairs.

New York City was the home to America’s two leader pictorial magazines, Life and Look.

Look magazine, which was founded in 1937, was the biweekly rival to the weekly Life. Out of the two, Life tended to feature more wholesome content and cover more international events. Look sought “a lower, broader field” than Life and unlike their rivals, they rarely covered breaking news, due to the longer lag time between issues. The advantage of this is they could be more freewheeling in their search for the best stories.

During Kubrick’s time at Look, the magazine would sell on average 2.9 million copies per issue (figures for 1948). The magazine would peak at 7.75 million in 1969 with an ad revenue of over 80 million per year. In 1970, the magazine made a loss of $5 million, mainly due to television cutting into ad revenue, a slow economy and an increase in postal rates. In October 1971, Look published its final issue of the magazine. Circulation at the time was 6.5 million. Their rival Life magazine would also close the following year.

Photography in Later Life

Kubrick maintained the practice of using photos for storyboarding throughout his entire career. When shooting his early films, it was common for him to use a still camera to find his shots. In later films, he would use his director’s viewfinder instead, although he did continue to use still cameras for planning lighting and set design.

He would also use a Polaroid Pathfinder 110A for continuity on his pictures to check lighting and cameras exposures – this way he could see what the shot would look like before shooting the scene.

On Barry Lyndon, Kubrick famously used a 50mm f/0.7 Zeiss still-camera lens – which had originally been designed for NASA – mounted on his Mitchell BNC camera. The f/0.7 lens enabled him to shoot scenes by candlelight, using the fastest film available at the time: Kodak’s 5254, rated at 100 ISO. This super-fast lens captured rooms lit only by candlelight and natural light sources perfectly, creating a unique look, unlike any other film.

What Cameras Did Stanley Kubrick Use?

As mentioned before, Kubrick’s father bought him a Graflex Pacemaker Speed Graphic Camera when he was thirteen, this was later followed by a Kodak Monitor 620 when he was sixteen and then a Rolleiflex K2.

In 1948, Kubrick (19 at the time) gave an interview to a magazine called The Camera. In the article, titled Camera Quiz Kid: Stan Kubrick, Kubrick reveals that he uses a Rolleiflex Automat (6×6 Model RF 111A), a 4×5 Speed Graphic and a 35mm Contax II camera for his work. During this time, Kubrick also used a Leica IIIc.

The interview also revealed that when shooting interiors, Kubrick prefers natural light, but switches to flash when the dim light restricts the natural movement of the subject and it’s unavoidable.

And for a series of candid photographs shot mostly at night on the NYC subway, “Kubrick used a Contax…at 1/8 second. The lack of light tripled the time necessary for development.” But as Kubrick recalled, “I wanted to retain the mood of the subway, so I used natural light.”

Kubrick continued to use various cameras throughout his life and would always be seen with a camera on-set. Here are the other cameras he used:

- Rolleiflex Automat 6×6 Model K4

- Rollei 35

- Pentax K (Tower 29)

- Hasselblad

- Nikon F

- Nikkormat FTn

- Nikon S2 (5cm F/1.4 and then with the 3.5cm F/1.8)

- Polaroid Pathfinder 110A

- Polaroid OneStep SX-70

- Subminiature Minox

- 35mm Widelux

Camera Buying Advice

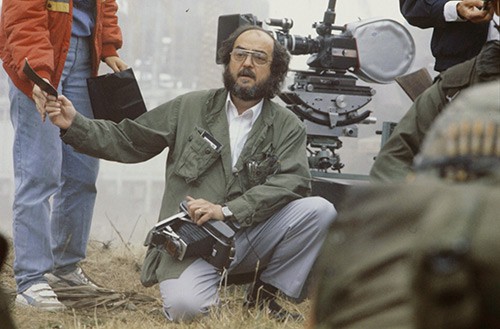

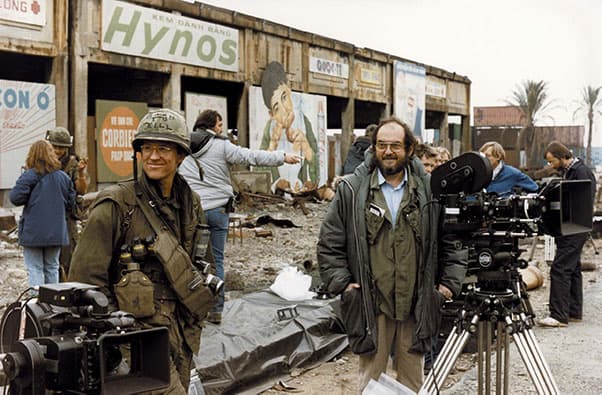

Matthew Modine tells a story from the filming of Full Metal Jacket (1987). Aware of Kubrick’s background in photography, Modine showed up on the first day of shooting with a Rolleiflex, the same model Kubrick used during his early days with Look, hoping to spark conversation over a shared interest.

I was nervous. I was going to meet Stanley Kubrick. I had the camera around my neck, trying to impress him with it, and then one day he looked at me and said, “What are you doing with that old piece-of-shit camera?” And I said, “Well, it’s a Rolleiflex…” and he cut me off saying, “I know what it is.” He told me to get this new Minolta auto-focus, all the lenses I needed, he even told me what camera bag to buy.

I didn’t like the Minolta, but I loved the Rolleiflex because of the way people behaved in front of it. It was a dyslexic camera and in that way it kind of made the world make sense. Upside down and backwards. I kept that camera with me, when we went to Vietnam and at boot camp, inside my flak jacket and when we were filming, and I saw something interesting I would snap a picture. I had prints made and I gave them to the different actors I took pictures of. I gave pictures to Stanley. His criticisms about exposure and composition were invaluable.

Matthew Modine

Kubrick never one for sentimentality or outdated tech, made him buy a Minolta 7000 instead, which Modine did and hated it.

Best Camera for the Job

What’s interesting is that the Rolleiflex is considered one of the best cameras ever made, and far superior to the Minolta that Kubrick suggested.

I think, like most people, Kubrick was just always looking at new technology and was excited to see what it could do. Kubrick loved cameras, as the following quote from The Stanley Kubrick Archives book demonstrates:

From the start I loved cameras. There is something almost sensuous about a beautiful piece of equipment.

There is no doubt he would be using both digital and film for photography and filmmaking today. Hollywood special effects supervisor, Dennis Muren once said in an interview that Stanley would always ask him about the progress of digital technology.

One of the behind the scenes photos from, Eye’s Wide Shut show Sydney Pollack looking at the back of his Sony Cyber-shot F3 digital camera while Kubrick watches him playing with his new toy. Kubrick also owned five IBM computers way back in 1983! There’s a funny clip of him trying to get head around MS-DOS in 1984, which you can watch here.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick also pre-envisioned the iPad. You see them in his film. More than 40 years before Steve Jobs would make them a reality. Samsung even challenged Apple’s patent claims by citing the tablet devices used by the astronauts in Kubrick’s film as “prior art”. So, if you want to create the next big thing, re-watch 2001 and see where your imagination takes you…

In the video below Tyler Knudsen (also known as Cinema Tyler) gives an overview of what cameras Kubrick used during his career. Please note that some of the cameras in the video are incorrectly identified. For a full list of Kubrick’s still cameras, please refer to our list above.

Other Stanley Kubrick Resources

Recommended Stanley Kubrick Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases. All links to Amazon are affiliate links, which means we receive a small commission for any purchases you make. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, but this commission keeps Photogpedia running and is the reason we’re able to offer so much free content.

To learn more, read our Affiliate Disclosure page. Thank you for your support.

- The Stanley Kubrick Archives (Taschen, 2008) * My favorite book

- Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick (Taschen, 2018)

- Stanley Kubrick: A Biography by John Baxter (Harper Collins, 1998)

- Stanley Kubrick – A Life In Pictures (Little Brown, 2002)

Stanley Kubrick Photography Videos

The Kubrick Files Ep. 4 – Kubrick’s Photography

Here’s another brilliant video from Tyler that provides an excellent overview of Kubrick’s photography work. These video essays were written and produced by Tyler Knudsen (Cinema Tyler). Be sure to subscribe to his YouTube Channel for more great videos.

Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures

Life in Pictures is probably the most definitive biography about Kubrick out there. This amazing documentary about the master film director covers his life from growing up in the Bronx to his last days making Eyes Wide Shut. Narrated by Tom Cruise, the documentary features interviews with Kubrick’s family, friends, collaborators, and cast including Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, Malcolm McDowell, and Matthew Modine. A must watch for any fan of Kubrick (or serious filmmaker).

The Art of Stanley Kubrick

This biography on Stanley Kubrick was included on the Dr. Strangelove DVD. The quality isn’t the best, but if you want a brief overview of his early life and work then this is the video for you. It features interviews with fellow filmmakers, actors, and collaborators.

More Stanley Kubrick Photographs

You can view more Stanley Kubrick photos at the Library of Congress and MCNY websites.

Fact Check

With every photographer article we produce, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Kubrick’s photography work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

The website was put together by photographers for photographers, so we can all learn from expert photographers (and filmmakers) like Stanley Kubrick. The more links we have to us, the easier it will be for others to find the website.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Recommended Stanley Kubrick Links

Stanley Kubrick Archive

The Stanley Kubrick Exhibition

Kubrick’s Cinematography Links

You can learn a lot about photography by studying how the great filmmakers photographed their films. Check out these interviews with Kubrick’s cinematographers where they discuss everything from lens choice to lighting to camera movements.

Filming 2001: Space Odyssey, American Society of Cinematography

The Old Ultra-Violence Clockwork Orange, American Society of Cinematography

Photographing Barry Lyndon, Scraps from the Loft

Flashback Barry Lyndon, American Society of Cinematography

Behind the Cameras on the Shining, Scraps from the Loft

Flashback the Shining, American Society of Cinematography

Sources

The Stanley Kubrick Archives, London College of Communication

The Camera, Camera Quiz Kid: Stan Kubrick, October 1948

Stanley Kubrick Raps, Charlie Kohler, 1968

The Film Director as Superstar, Joseph Gelmis, 1970

Cowles Closing Look Magazine After 34 Years, NY Times, 1971

American Cinematographer, Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic collaborators recall the man, October 1999

Kubrick by Michael Herr, 2001

Looking Back on Stanley Kubrick, LACMA, 2013

The Right-Hand Man: Jan Harlan on Stanley Kubrick, BFI, 2013

The Killer Inside You: Matthew Modine Interview, Maxwell Kupper, 2013

Photojournalism, Arthur Rothstein, 1974

Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, John Baxter, 1998

Kubrick, Michel Ciment, 2001

Stanley Kubrick: Interviews, 2001

Stanley Kubrick – A Life In Pictures, Christiane Kubrick, 2002

The Stanley Kubrick Archives, 2008

Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine, Philippe Mather, 2013

Stanley Kubrick and Me: Thirty Years at His Side, Emilio D’Alessandro, 2016

Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick, 2018

Audio Interviews with Jeremy Bernstein, 1966

Stanley Kubrick – A Life In Pictures DVD, 2002

Kubrick Remembered Documentary, 2014

Special Thanks

Special thanks to the Stanley Kubrick Archive team based at the London College of Communication, who granted me permission to visit them on several occasions. I’m very fortunate to have this wonderful resource on my doorstep. I’m also extremely grateful to the Kubrick family, for making the archive available to the public.

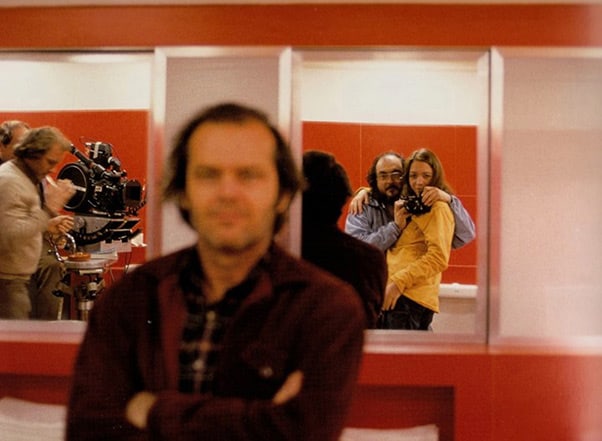

Looking at scripts and studying Kubrick’s notes on story and character development has been an invaluable experience. I’ve also had the opportunity to see Mr. Kubrick’s negatives and photos from his early days at Look and his films. His publicity photos for The Shining – which were never used – are incredible, and just as good as any other photographer I have studied.