Norman Parkinson was a celebrated fashion and portrait photographer, whose photographs helped define the look of fashion and culture for over fifty years.

One of the great pioneers of fashion photography, he established his studio in 1934 and quickly became one of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue’s most important photographers.

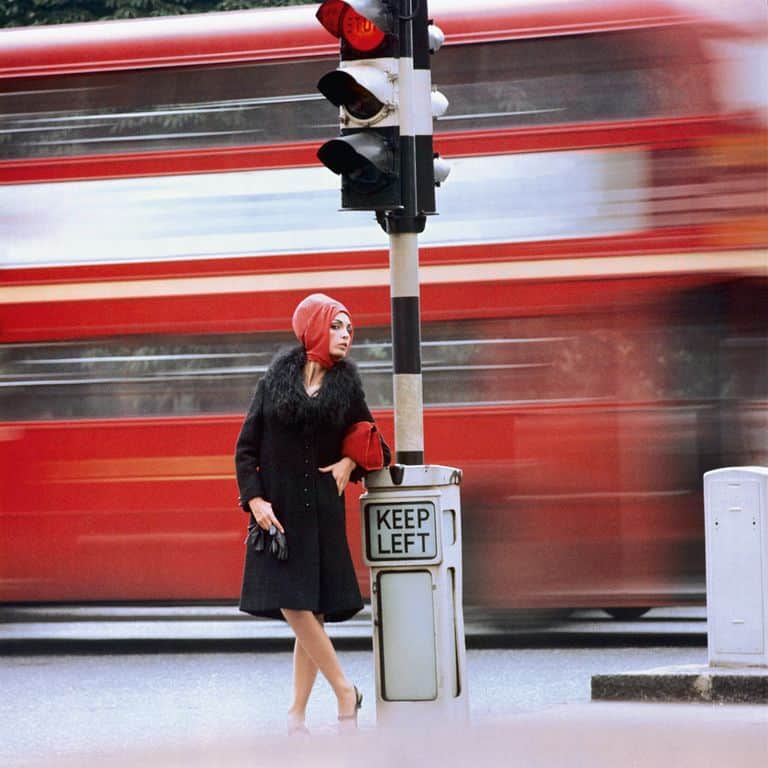

Parkinson pushed the boundaries of the day and revolutionized photography in the ’40s by bringing his models out of the studio and onto the street.

He continued to reinvent himself (and fashion photography) throughout his career: from his ground-breaking, spontaneous images of the 1930s, through to the Swinging Sixties and then the exotic location shoots of the 1970s and 1980s.

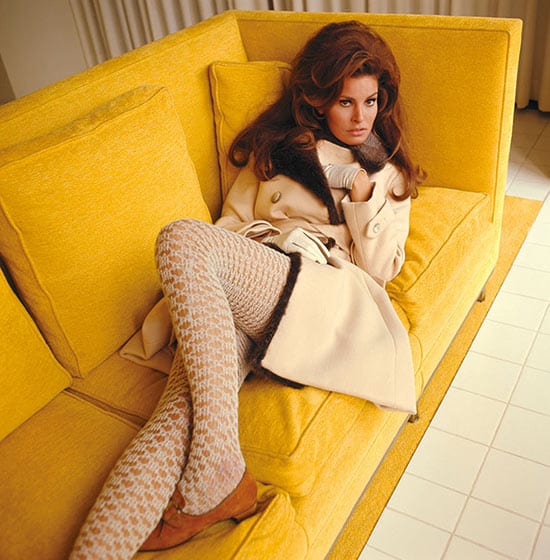

His portraits of icons such as Audrey Hepburn, Raquel Welch, and Jerry Hall brought him worldwide recognition. He was also a favorite photographer of the British Royal Family.

Over the half-century he was taking photographs, Norman Parkinson produced some of the most memorable fashion images and portraits of the 20th century.

The British photographer was one of Vogue’s star contributors and enjoyed a relationship with the magazine that lasted over four decades. He also worked with other publications including Harper’s Bazaar, Queen and Home and Country.

Related: Top 15 Norman Parkinson Quotes on Fashion and Portrait Photography

I like to make people look as good as they’d like to look, and with luck, a shade better.

Norman Parkinson

Table of Contents

Norman Parkinson Biography

Name: Ronald William Parkinson

Nationality: English

Genre: Fashion, Portrait, Advertising

Born: 21st April 1913 – London, England

Died: 15 February 1990

Early Life

Ronald William Parkinson was born on the 21st of April 1913 in Roehampton, London. The son of a London barrister he attended Westminster School with an interest in art.

Parkinson’s photography journey began at eighteen when he began an apprenticeship with the noted court photographer Richard N Speaight at Speaight and Sons.

Based out of Bond Street in London, the firm’s founder was the first photographer to take a studio portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. It was here that Parkinson learned to master studio photography.

In the 1930s, apprentices paid a fee to work under such people, and Parkinson’s paid three hundred pounds (the equivalent of £15,000 today) to learn from the photographer.

Becoming Norman Parkinson

After completing his apprenticeship, Parkinson, now twenty-one years old, partnered with another young photographer, Norman Kibblewhite, and opened up a studio at No 1 Dover Street in Mayfair.

The men merged their names, creating Norman Parkinson and a legendary force was born.

They started out specializing as photographers of debutantes (a young woman of upper-class family or aristocratic background).

The partnership was short-lived, but Parkinson decided to keep the name they established.

He started to get commissions from a variety of magazines including The Sketch, The Tatler, and The Bystander, and even photographed some of the top celebrities of the day including Noel Coward and Vivian Leigh.

Enter Fashion Photography

His entry into the world of fashion photography was unplanned.

Joyce Reynolds, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, was visiting another photographer at Parkinson’s studio in Dover Street when she spotted some landscape pictures taken by Parkinson on holiday in Italy, which were mounted on the wall. Reynolds was entranced by the images.

The following day she commissioned Parkinson to photograph two models posing in hats in Green Park. That first job was the start of a close relationship with the British edition of Harper’s Bazaar.

While working for the magazine, Parkinson began taking action photographs of models outside, which helped champion a ground-breaking new style.

Most photographers showed women standing in scintillating salons with their knees bolted… I never knew any girls with bolted knees. I only knew girls who jumped and ran.

Norman Parkinson

Parkinson pioneered this style, which was dubbed “action realism” and his work was in high demand.

Moving to Vogue and Wenda

In early 1941, Parkinson left Harper’s Bazaar and embarked on an enduring creative relationship with Vogue. From the July 1941 issue until 1960, Parkinson was one of the top contributors to the British edition of the magazine.

During the Second World War Parkinson served as an aerial reconnaissance photographer for the Royal Air Force.

After the war ended, fellow photographer Cecil Beaton introduced Parkinson to an aspiring actress named Wenda Rogerson. The two started to work together in 1947 and she became his greatest muse.

They were married for forty years until her death in 1987. Their partnership would create some of the best-known and most beloved Parkinson images.

Whatever style and elegance might be attributed to my work, most of it was Wenda Rogerson’s influence.

Norman Parkinson

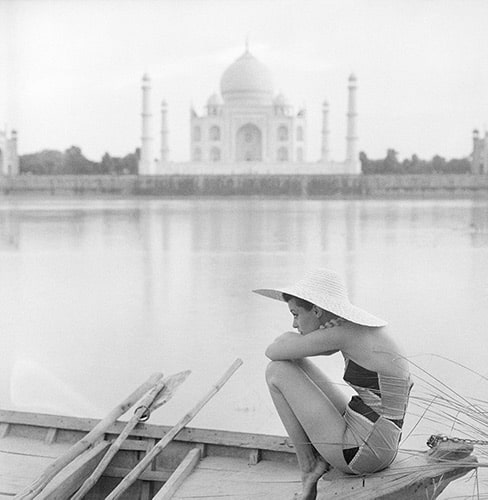

The couple traveled extensively, often on assignment to exotic locations such as the Caribbean, South Africa, and India. All modeling locations practically unheard of at the time.

Once the world became more accessible through air travel, everything opened up for him and the possibilities were endless.

The world is my studio.

Norman Parkinson

And his world of course included New York City.

American Vogue and New York

In New York, Parkinson was courted by the famed art director at American Vogue, Alexander Liberman.

Parkinson’s work for Vogue would further his already growing reputation as one of the finest fashion photographers around, with many of his images featuring on the cover as well as given significant space in the influential magazine.

On his first trip to New York, Parkinson was introduced to a new face in the modeling world, a teenager named Carmen Dell’Orefice. Parkinson began working with the model, then aged eighteen, in 1949.

The friendship between the photographer and model would last throughout his life, and the two of them would collaborate on countless sessions, resulting in many cover images and editorial spreads that have since become iconic.

Parkinson wasn’t looking to show the ugly of life. He was trying to portray the beauty and harmony. He controlled his lust through his art form. And he was such a gentleman.

Carmen Dell’Orefice

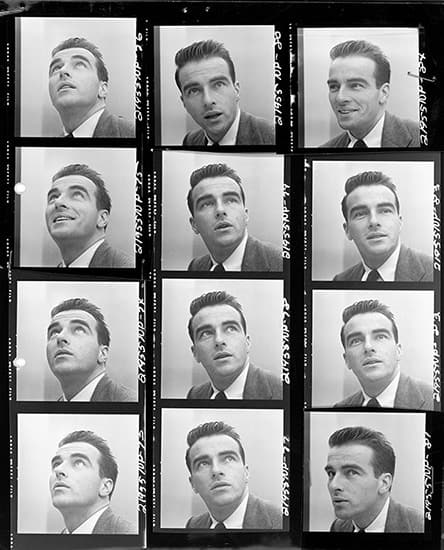

During his time in New York, Parkinson captured portraits of stars such as Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, Ava Gardner, and Katherine Hepburn.

Parkinson also photographed rising star Audrey Hepburn, then only twenty-two years old, at the same time as her Broadway debut, Gigi.

Color Photography

In the 1940s, Parkinson also began using color film, which added a new dimension and vividness to his work.

In Alexander Liberman’s book, The Art and Technique of Color Photography, published in 1951, Parkinson’s photographs featured heavily. The photos include Parkinson’s first color nude study, which was previously published in the Vogue Beauty Book earlier that year.

The modest Parkinson attributed his success to “gremlins in the camera” and from the mid-50s onward, he wore a Kashmiri wedding cap to bring him good luck on assignments.

Re-Launch of Queen Magazine

In 1959, Parkinson left Vogue when he was offered the job as Associate Editor and Contributing Photographer to the newly re-launched Queen magazine.

The British magazine, initially published fortnightly, was aimed at the emerging youth market of the time.

The style-setting magazine was perfectly poised for the Swinging Sixties, and Parkinson, who was now in his late forties, was provided with an opportunity to be at the forefront of exciting cultural changes.

Queen magazine and the job offer came at the perfect time. The magazine, would become one of the most popular and influential magazines of the early 60s.

The covers and editorial assignments Parkinson shot for Queen not only reflected the changing times but also allowed the master photographer to capture images of some of the most notable new stars of the day, such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Fashion remained in Parkinson’s heart though – and in front of his lens – and he used his experience to spot new faces that would go on to define the decade, including Twiggy, Celia Hammond and Jill Kennington.

Parkinson was lured back to American Vogue, now under the editorship of Diana Vreeland, in the fall of 1963, and then British Vogue in 1965.

Moving to Tobago

With younger photographers such as David Bailey, Terence Donovan, and Brian Duffy – who Parkinson dubbed as “the black trinity” – getting attention and more calls from editors, Parkinson decided to spend some time abroad.

Parkinson and Wenda moved to Tobago, building themselves a home in an idyllic setting overlooking an unspoiled bay.

In Tobago, Parkinson set up a pig farm, and for years his Porkinson Bangers were served at the Ritz and on Concorde.

However, semi-retirement didn’t suit Parkinson and he was soon back at work, using Tobago as his base to travel internationally and for many of his fashion shoots.

The Royal Photographer

In 1968, Parkinson was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society. The same year, he started to receive royal commissions, which included the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales.

In 1973, he was appointed the official photographer for Princess Anne’s wedding, an appointment that many expected Cecil Beaton to be given. He would later become the official photographer to the British monarchy in 1975.

Parkinson’s Later Career

In the 1970s, Parkinson once again redefined fashion photography, taking his models to far-flung places and exotic locations including Versailles, Jamaica, and Barbados.

He also embarked on a groundbreaking trip for British Vogue to the Soviet Union with Jerry Hall and former model and now prominent creative director of Vogue Grace Coddington.

[Parkinson] taught me everything I know – I always say he’s my number one mentor. I adored him.

Grace Coddington

As the ’70s came to a close, Parkinson decided to leave Vogue and began working for the lifestyle and travel magazine, Town and Country.

Sir Ronald Parkinson was awarded a CBE by Queen Elizabeth II in 1981 for his achievements in photography. That same year, he took his famous Blue Trinity portrait of the Queen, the Queen Mother, and Princess Margaret.

In 1981, Parkinson was also given a major retrospective exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The exhibition, showcased more than 240 images and attracted a record-breaking number of visitors. It included several commissioned photographs, including portraits of iconic couple Jerry Hall and Mick Jagger, then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher and fashion designer Zandra Rhodes.

Parkinson was selected to shoot the Pirelli calendar in 1985. The theme of the calendar was fashion and he shot models such as Iman and Anna Andersen wearing clothes and accessories matching the companies tyre pattern.

Parkinson’s Last Days

Norman Parkinson never retired from photography. He died in February 1990, at the age of 76, after being taken ill while on assignment in Malaysia.

His last photographs, The Mermaid’s Tale, were posthumously published as the cover story in the May 1999 issue of Town and Country magazine.

There are very few photographers who remember that photography can be an expression of a man’s deepest creative instincts. [Parkinson is] among those who have never forgotten.

Richard Avedon

Photography Style

- Action realism

- Use of outdoor locations

- Movement, spontaneity

- Mastery of color

- Layering images

Parkinson always claimed that he was a craftsman, not an artist and that his pictures happened more or less by chance – he was of course being modest.

Parkinson understood light and had a mastery of color. His ability to find photos and his photographic eye were second to none. So much so, that even today, photographers and fashion editors continue to use his images as a source of inspiration and reference.

He taught me everything about being an editor, and really keeping your eyes open all the time. To just keep watching. Keep looking. And take in everything so you can feed that back into your work.

Grace Coddington

Like many of the greatest photographers, Parkinson would continue to reinvent himself throughout his career, making an enormous contribution to world of fashion photography and contemporary art in the process.

Parkinson wrote in his autobiography “My aim was to take moving pictures with a still camera”.

How to Shoot like Parkinson

Parkinson took his models out of the studio and into the real world and was a pioneer of what would be known as “action realism” photography.

He was heavily influenced by Martin Munkacsi whose own style captured the movement and speed of the 1930s.

He was a master of photography, who had perfect control over every aspect of the image: light and shadows, composition and direction, and style.

Finding Photos

Although he was a meticulous planner, who understood what he wanted, he wasn’t afraid to adapt if something better came along.

One of Parkinson’s greatest talents was in finding images and creating unique visual stories.

When I arrive at any place in the world I buy postcards because then you find out where all the places you should be are.

Norman Parkinson

That’s the biggest lesson he taught me: not to rely on other people’s opinions but to forge your own, really explore and look. It’s certainly done well for me.

Grace Coddington

Creating Timeless Photos

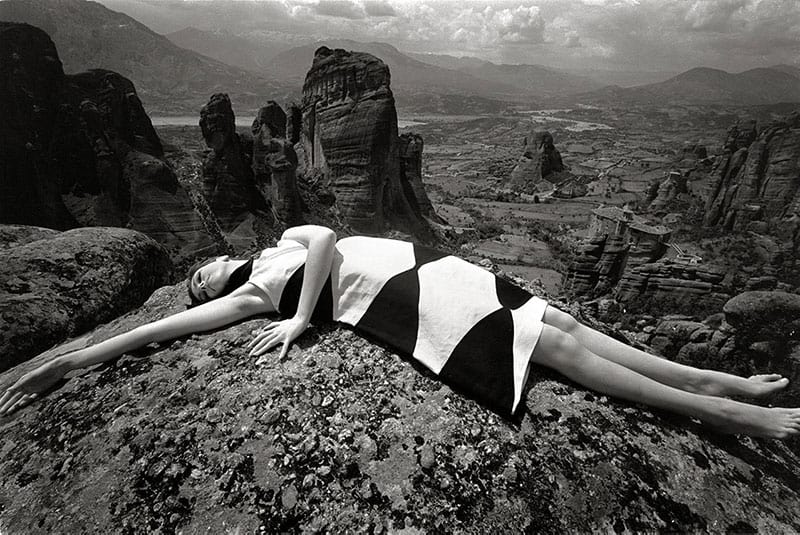

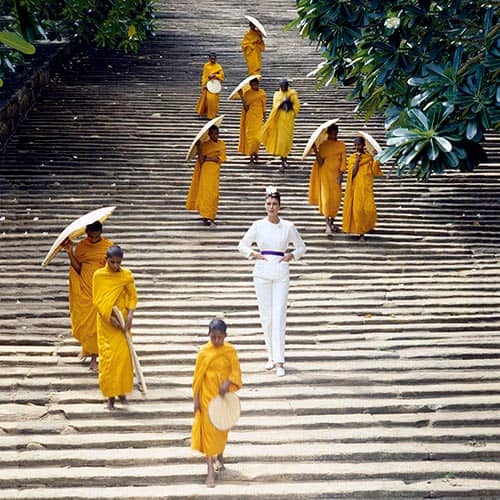

He would often layer his photos with his subject in the foreground and another visual element (landscape or person) in the background – not to distract the viewer but to give them a glimpse into another culture and to add more depth to his images.

If you look at his photos from India, Sri Lanka, USSR (or anywhere else) they all incorporate the location, giving his images a sense of time and place. The older the images are, the more interesting they become.

I think that to be a really great fashion photographer, your pictures have to capture the imagination of people and be timeless, and very few photographers manage to do that.

There are lots of photographers who make fashion look great, who make you look beautiful, who sell lots of clothes and do a great job, but they don’t capture a moment in time.

That’s a special quality, and I think Parkinson proved again and again that he had it. When you look at his photos, you see how many of them stand out. When they’re made into postcards or posters, there’s always something that you remember. The women seem alive, they’re quirky.

Jerry Hall

Working with Models

The laid back atmosphere on a photoshoot put his models at ease, which was reflected in the photos. Parkinson coaxed his models into getting “the shot” before it was the thing to do and made the working process fun for everyone involved.

Parkinson always worked with a small team – aside from himself there would be one assistant, a fashion editor, and a model on set, and his wife Wenda would always come too and write the travel piece that accompanied the photoshoot.

He created these pictures that we’re still looking at today and loving for their looseness and movement – they’re never stationary. The model isn’t necessarily rolling around with laughter, but there is always a lot of joy, and that’s down to the fact he was a funny man, charming, and he made them feel comfortable.

Grace Coddington

His charm enabled him to get the models to perform on the edge (quite literally) – models would stand on bridges, cliffs and other precarious locations to get the perfect shot.

His photos were often edgy and dangerous and he wasn’t afraid to experiment to get his image.

He had a sense of “big” – you know, big spaces – he would choose panoramic views and had a great sense of movement across the page. He always enjoyed you moving, doing some kind of a shape, which I really enjoyed, too.

Jerry Hall

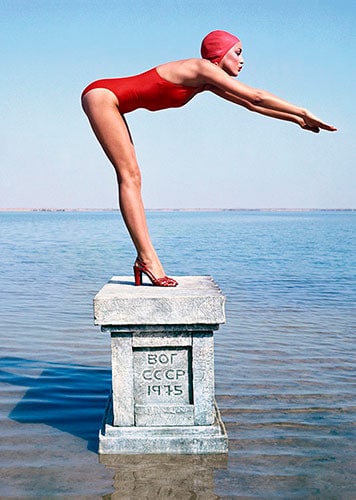

He was always saying, “Climb up on that thing!” I went up on oil rigs in Russia waving giant flags, stood on a plinth in a red swimsuit in the Red Sea. He had me on a horse, bareback, in a blue dress, and the horse took off and threw me into a barbed-wire fence.

I broke my tail bone and he came up and said, “You all right?” and I said, “I think so”, blood everywhere. And he said, “I thought you said you were from Texas!” He made me get right back on another horse and do the picture.

Jerry Hall

Parkinson’s Lighting

Parkinson loved to shoot outdoors, where he could take advantage of natural light.

[I like to work] in the sunshine. I never work in studios if I can help it, because working in a studio is such hard work. The greatest photographs always have in them some sort of unplanned accident: the movement, the fun, the gaiety.

Norman Parkinson

His photos were typically shot against the light (contre jour) with flash used to light the foreground and fill in the shadows. This method of lighting gave Parkinson more control over the light on location.

When you shoot with the sun behind you, you’re very limited in how you can control or modify your light source – using fill flash would allow him to balance the light from the foreground against the light behind the model.

There’s no light like daylight. All the lights you use in the studio are only to approximate daylight. We go outside and use the sunshine and people feel so good. In the studio it’s like an operating theatre, where only blood is left. You come out in the sunshine – everybody’s at home in the sunshine… This is what gives us life, and my pictures, give a lot of life.

Norman Parkinson

What Camera Did Norman Parkinson Use?

Parkinson started his career using large format cameras but later switched to a Hasselblad medium-format camera which he continued to use until his death. He also used Nikon F 35mm cameras for location work which involved a lot of movement.

On assignment he always carried two of everything: two medium format cameras (Hasselblad’s) and two 35mm cameras (Nikon F’s).

In 1981, Parkinson said that he hadn’t used an exposure meter for over twenty years! Although he did take Polaroids to check his final exposure before committing to more film.

He used both black and white and color film, although later in his career he preferred to use color for the majority of his work and only used black and white for backup.

I’ve been slowly slipping out of black and white and now I only take it under sufferance as a sort of back-up to my color snaps

Norman Parkinson

Norman Parkinson Random Facts

- In 2013, Google celebrated Parkinson’s 100th birthday with his own doddle. Google UK changed its logo to incorporate an illustration of the photographer for the day.

- Also in 2013, the iconic photographer was included in a collection of First Class stamps released on the theme of “Great Britons” by the Royal Mail.

Other Parkinson Resources

Recommended Norman Parkinson Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

Norman Parkinson Videos

Interview with Thames TV, 1977

Rare Footage of Norman Parkison

Norman Parkinson Photos

Table Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa, British Vogue, 1951© Norman Parkinson Estate

Jerry Hall at Versailles, British Vogue, 1975 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Pilar Crespi, Town & Country, Sri Lanka, March 1980 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Wenda Parkinson and Foot Guard on duty, Buckingham Palace © Norman Parkinson Estate

Raquel Welch, American Vogue, August 1967 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Apollonia van Ravenstein at the Lannan Foundation, Palm Beach, Town & Country, 1983 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Carmen Dell’Orefice, Town & Country, May 1981. An American Fantasy © Norman Parkinson Estate

Wenda Parkinson, Vogue, 1954 © Norman Parkinson Estate

British Vogue, May 1957 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Katherine Pastrie in Mexico for Vogue, 1966 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Barbara Mullen with a child in India for Vogue magazine in November 1956 © Norman Parkinson Estate

Jerry Hall for British Vogue (cover), May 1975 © Norman Parkinson Estate

View more Norman Parkinson photos at Iconic Images or visit the official Norman Parkinson website

Contact Sheets

Fact Check

With every photographer profile article, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Norman Parkinson’s work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through social media or your own blog.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Sources

Iconic Images: Norman Parkinson

Norman Parkinson, Photographer, Adventurer, and Royal Gadfly, The New York Times, 1990

Legend Behind a Lens: Norman Parkinson, Financial Times, March 2013

The Wild Man Who Re-Invented the Fashion Shoot, Telegraph, 2015

Grace Coddington on Norman Parkinson’s Legacy, Vogue, 2019

One Pair of Eyes: Norman Parkinson, BBC, 1967

Interview with Thames TV, 1977

Kenneth Williams Interview with Parkinson, Wogan Show, 1986

Norman Parkinson: A Very British Glamour, Rizzoli, 2009

Always in Fashion: Norman Parkinson, 2019