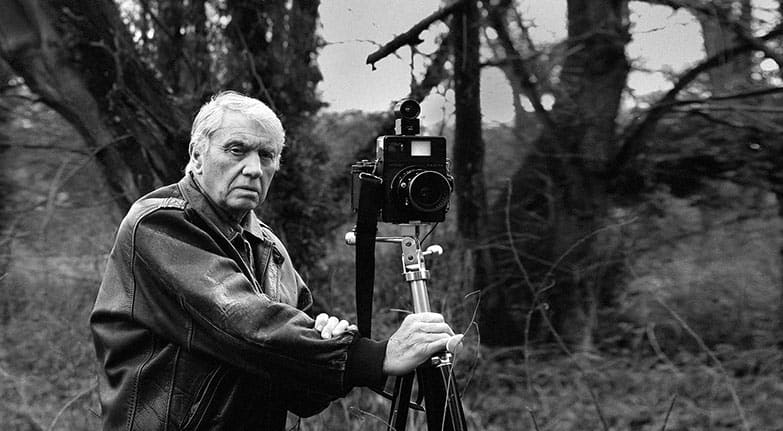

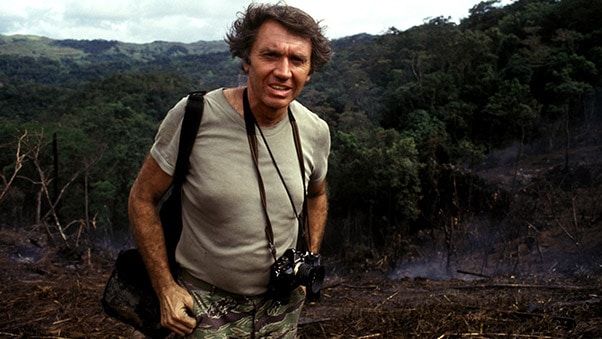

Internationally acclaimed photographer Don McCullin is one of the greatest living photographers today. With a career spanning over 50 years, he has established himself as one of the most respected photographers of our time, producing some of the most iconic and important images of the last century.

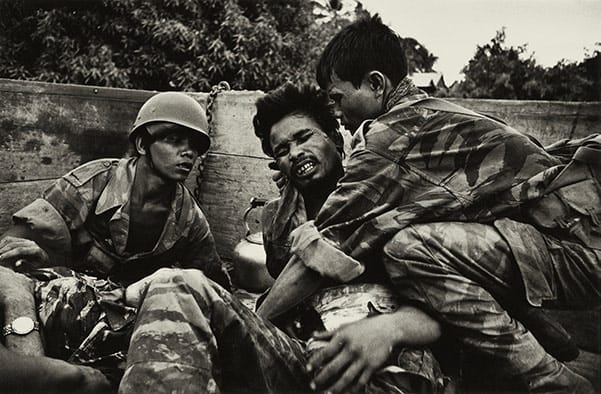

To capture those images, McCullin risked his life on many occasions. He was shot and wounded in Cambodia, expelled from Vietnam, had a bounty on his head in Lebanon and imprisoned in Uganda. He’s also braved bullets and bombs not only to get the perfect shot but to help wounded civilians and dying soldiers. Compassion and emotion are at the heart of all his photojournalism work.

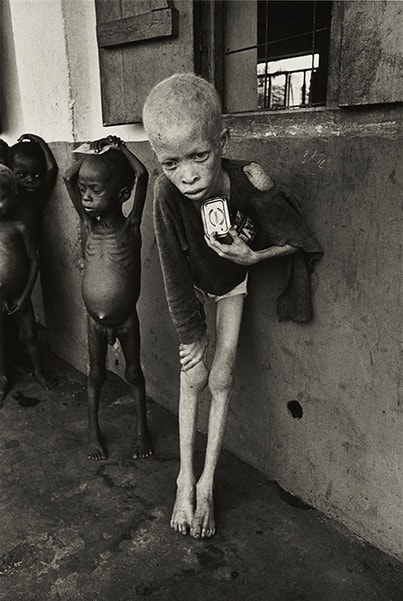

McCullin has proved himself a photojournalist without equal, whether documenting famine in Africa, poverty on the streets of London’s East End or the horrors of war in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Congo. Many peers including photojournalists at world-renowned Magnum have called him the 20th century’s greatest photographer.

He is also well known for his landscape photography, producing powerful black and white photos of the Somerset countryside – where he has lived for 30 years – as well as France, India and the rest of Britain.

In 2013, he became the first photojournalist to be awarded a CBE and in 2017 he received a knighthood for services to photography. Now in his 80’s, Sir Don McCullin remains a compassionate chronicler of our world. Let’s hope he continues to photograph for many years to come.

Related: 58 Don McCullin Quotes on Photography and Life

I feel at the edge of my journey with photography now. I’m older, more knowledgeable, but I’m never satisfied, never arriving, always looking for something better to come. I’m a lost soul without photography.

Table of Contents

Don McCullin Biography

Name: Don McCullin

Nationality: English Photographer

Genre: Photojournalism, War, Landscape, Documentary, Portrait

Born: 9 October 1935 (age 84 years) – London, England

The Life and Career of Don McCullin

Early Life

Don McCullin was born in 1935 in Finsbury Park, a poor and rough area of London at the time. Growing up during World War 2, McCullin was exposed to war from an early age.

Like all my generation in London, I am a product of Hitler. I was born in the thirties and bombed in the forties.

Don McCullin, Unreasonable Behaviour

As a child, the dyslexic McCullin found schoolwork difficult but excelled in drawing and painting, winning a scholarship to the Hammersmith School of Arts and Crafts. After the death of his father in 1950, he was forced to forfeit the scholarship and left school at fourteen without any qualifications.

After leaving school, McCullin first worked as a dishwasher on a steam train and then as a messenger boy for an animation studio in Mayfair, delivering cans of film.

When he was called up for National Service in 1954, he told recruiters that he worked in the movie industry, so he was placed in the Air Force, renumbering old wartime film stock at RAF Benson in Oxfordshire.

Later, he would be posted to the Canal Zone during the Suez Crisis in 1955. He was first sent to Kenya then Egypt and finally Cyprus, working as a photographer’s assistant.

McCullin worked in the darkroom, handling photographic paper and chemicals, printing up to three and half thousand photos daily. It was during his time in Kenya, that he developed an interest in photography and purchased his first camera, a Rolleicord.

For thirty pounds I bought a new Rolleicord camera. I went into Nairobi and photographed people at the bus stations. That was my first real encounter with film and photography.

Start in Photography

McCullin completed his National service in late 1956 and returned home, finding work as a darkroom assistant for the animation company he worked for prior to his stint in the Air Force.

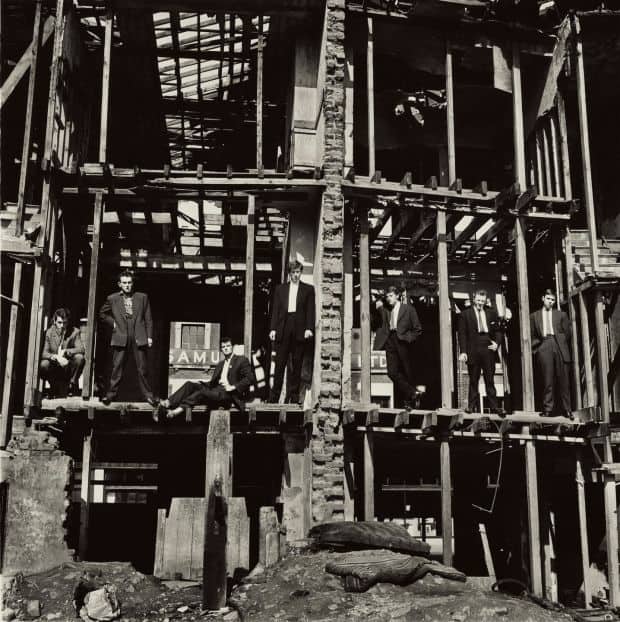

Armed with his new camera, he began photographing friends from a local gang named “The Guv’nors”. After one of the members of the gang was arrested for murdering a policeman, McCullin was persuaded to show his photos to the picture editor at the Observer newspaper.

In 1959 the Observer newspaper published a story about a gang and its murder of a policeman in north London. Alongside it was my photograph of the gang, who lived in the area where I grew up. Seeing my name under the photograph (and being paid the princely sum of £50) gave me an enormous feeling of achievement. Where we came from you read only the Sunday Graphic or the News of the World. The most important thing to me was to see my father’s name on the page. All my working life I’ve driven myself to make his name have some meaning, which I think I’ve just about achieved.

The Newspaper paid McCullin £50 for image rights. At the age of 23, McCullin earned his first commission and began his career in photography, which was more by accident than design.

That gang picture was the ticket to rest of my life.

Learning Photography

Frankly, I didn’t really know anything about photography. I’d just been taking snaps. I had to learn very quickly. But after that famous picture of the gang was published in The Observer, I was offered every job in England – just because of that one picture.

McCullin was a self-taught photographer. He learned photography through experience and by buying a stack of second-hand books in 1965 when he was working at The Observer. The photograms and books he acquired were published between the dates of 1886 and 1926.

They cost me ten quid, which was a lot as I didn’t earn much. Those books became my photographic university. I still refer to them today. You never stop learning. You never stop discovering. I’m constantly being surprised.

Shaped by War, 2010

Photography Career

Then I got married and went to France. I was in the Café de Flore in Paris, and I looked over this bloke’s shoulder who was reading the newspaper and saw that famous picture of an East-German soldier jumping over the barbed wire. I said to my wife, “After we go back to England, would you mind if I went to Berlin?” This was in 1961, and my wife would never say no – she was very kind and sweet. So, when we got back to England, I rang The Observer and said, “I’m going to Berlin”, grabbed my last seventy quid out the bank, bought an airline ticket and rolled up in Berlin. I stayed there a week and shot everything on the Rolleicord.

This photo essay along with the images of “The Guv’nor’s” secured him a permanent contract with The Observer in 1961. That same year, he won the British Press Award for the Berlin Wall photo essay.

The War Photographer

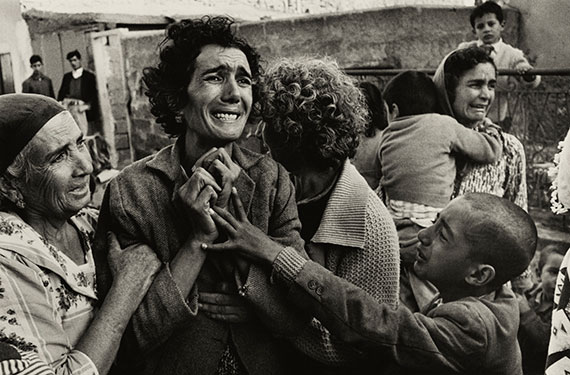

McCullin was assigned projects in London initially, but commissions soon took him around the globe, starting with the Cyprus War in 1964. This was McCullin’s first foray into a conflict zone and the images he produced are some of his finest. These photos earned him a World Press Photo Award and catapulted him into the field of international photojournalism.

I’ll tell you right now, Robert Capa had been killed in 1954 in Indochina, and there was this job vacancy – I wanted to be, not Robert Capa, but the best war photographer in the world, which is a really silly thing to say. I knew that, but I thought that you should look for an area that you’re suitable for. I came from Finsbury Park, I was tough, I wasn’t afraid, I challenged everyone who challenged me, I challenged everything. I thought, “I’m cut out for this job.” When I came back from Cyprus, I realized that – with my speed, and my attitude about war – that’s where I belonged. I suddenly found my little place in the world.

For the next two decades war became a mainstay of McCullin’s photojournalism, at first for The Observer and then from 1966, The Sunday Times. At the time the publication was one of the world’s most respected outlets for reportage stories and a perfect fit for McCullin’s hard-hitting images. He subsequently spent 18 years with the magazine and would often have as many as 16 pages devoted to his photo essays.

Photography has given me a life… The very least I could do was try and articulate these stories with as much compassion and clarity as they deserve, with as loud a voice as I could muster. Anything less would be mercenary.

Conflict Zone Assignments

McCullin’s assignments for The Sunday Times include Biafra (1969), Northern Ireland (1971), Bangladesh (1971), Uganda (the mid-70s), Afghanistan (1979), Lebanon (1982), and El Salvador (1980s). His best-known work from the period is his photos of the Vietnam and Cambodia wars.

It’s playing Russian roulette really; there’s no other way of putting it. There was a day when one of my cameras got hit by a bullet. I didn’t have a helmet or flak jacket, and there was a sniper that was killing all these guys around me. I was running across this paddy-field with ten Cambodian soldiers; one young boy was carrying a flag – he must have thought it was still Napoleonic days – and he was the first to get hit. Then all of the other guys got hit and I hid behind the radio operator because he had this big square metal thing on his back. That didn’t work, because bullets were lashing from all over, so I thought, “Fuck this, I’m not going to get killed”, and threw myself down in the water and slime.

To keep my cameras dry, I was dragging them along the side of the paddy-field. I didn’t see the bullet hit my camera, but when the water ran out, I ran like fuck across this field. I could hear bullets and mortars going over, and I was zigzagging in order to be a bad target. When I finally got back about three-hundred yards, away and out of range, I was covered in mud and thought that I’d better check my cameras. And wallop, there was a bullet-hole in my Nikon.

Back in England

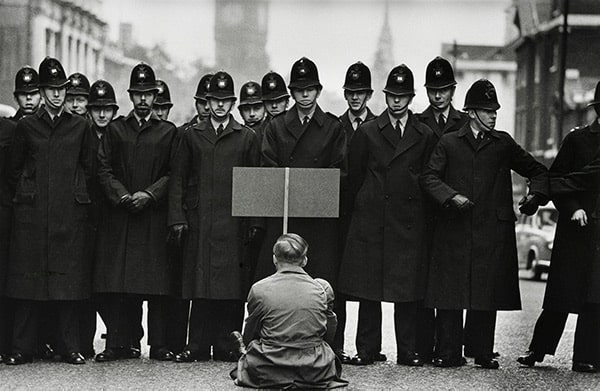

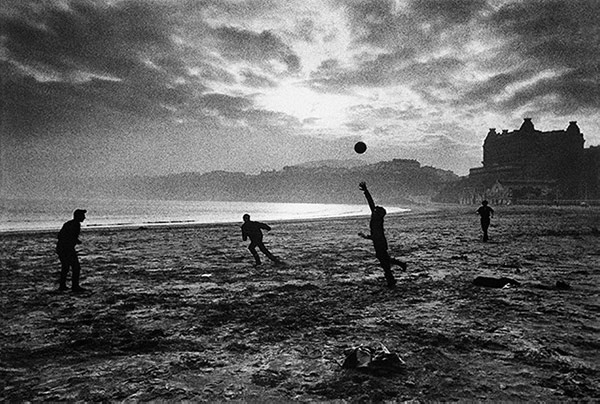

In the 1970s, McCullin turned his attention to England and the deep divisions of class and wealth in his homeland. For the project, he photographed the people of Bradford, Durham, Liverpool, and the homeless in London’s Whitechapel.

I had long been uncomfortable with my label of war photographer, which suggested an almost exclusive interest in the suffering of other people. I knew I was capable of another voice.

In 1982 the British Government refused to grant McCullin a press accreditation to cover the Falklands War. At the time he believed it was due to the-then Thatcher government deeming his images too disturbing politically. It later emerged that it was simply an administrative decision made by the Royal Navy who had already allocated their quota of press passes.

Then in 1984, when the world heard about the famine situation in Ethiopia, McCullin was left bitterly disappointed when The Sunday Times decided not to send him to cover the story.

I should have gone on my own, jumped on a plane by myself. It showed me up. I was at my best then. [Sebastião] Salgado deserved his praise, but this story was made for me. I was left at the bus stop.

Going Freelance

McCullin decided to leave The Sunday Times in 1984 and go freelance. After two decades of covering wars, he decided it was time to explore other genres of photography, devoting more time to his landscape and still life photography and accepting portrait commissions.

In the 80s and 90s, McCullin continued to travel internationally. He visited countries like Indonesia, India, Syria, and Africa, returning with powerful stories on places and people that, in some cases, had limited or no previous encounters with the Western world.

Perhaps his most notable and ambitious project in recent times was his exploration of the ruins of the Roman Empire across North Africa and the Middle East, which was documented in his book Southern Frontiers: A Journey Across the Roman Empire (2010).

Just Call Me a Photographer

McCullin dislikes being categorized as a war photographer, describing the term as “being like that of abattoir worker.” Throughout his career, he has also documented many humanitarian themes and events. He was once described as “a conscience with a camera” by Sir Harold Evans, the former editor at The Sunday Times.

In the ‘60s, McCullin took the images for the Beatles White Album. His photos from the photo session were later published in the book, A Day in the Life of the Beatles. He was also paid £500 to shoot the stills used in Antonioni’s film Blow-Up starring David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave.

Don McCullin’s reputation as one of the greatest photographers of conflict has since been replaced with Don McCullin the great travel and documentary photographer. Look at his work in Africa or his incredible black and white landscapes of Britain, India, and France to see the range and depth of his work.

Awards and Legacy

Don McCullin has been awarded countless awards including the Word Press Photo of the Year 1964, and the Cornell Capa Award by the International Center for Photography in New York in 2006 for his lifetime contribution to photography. In 1993, he became the only photojournalist to be made Commander of the British Empire (CBE) and in 2017 was awarded a knighthood for his services to photography. A well-deserved honor for Britain’s greatest photographer.

Sir Don McCullin is the author of more than a dozen books (mostly published by Jonathan Cape), including his acclaimed autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour (1990) and Don McCullin: The New Definitive Edition retrospective (2015).

His book, Shaped by War (2010) was published alongside a major retrospective at the Imperial War Museum North in Greater Manchester. The museum displayed over 250 of McCullin’s photographs, as well as his contact sheets and various personal memorabilia from his life in photography. In 2019, Tate Britain also presented a hugely successful major solo retrospective of his work.

Don McCullin’s Photography Style

When it comes to Don McCullin’s war photos, they are more a personal view of the conflict, rather than news stories. Not what happened, but what it was like.

When entering conflict zones, he would go in unobtrusively, remaining focused and disciplined while carrying very little equipment. He learned early on how to remove himself from dangerous situations and to trust his instincts. He also knew how to smuggle his film out if necessary.

A sense of timing is the most important part of the life of a professional photographer. I have an uncanny way of being at the right place at the right time. And if the time is not right, I can be patient, stay in that place for hours, willing things to come.

The most important thing was capturing the image and telling the story. Everything you need to know is there in his pictures. Yet there’s something about them that goes beyond their immediate context. His black and white photos of wars and famine are honest, truthful and still to this day continue to haunt.

We don’t live in a black and white world, but once you see a black and white photograph, it haunts you. I have done a few pictures of wars in colour, but they don’t work – they feel too cosy – while black and white photographs will penetrate your memory.

His photos may not be pretty, but they’re some of the most important in history and will continue to be viewed for many hundreds of years. How many photographers can say that about their work? Not many…

I look for drama – drama is the key factor in all my work.

The McCullin Approach

When it comes to understanding how McCullin works in the field, below are two excerpts from an interview with Aaron Schuman for Hotshoe Magazine in 2016. You can read the full interview (recommended) by clicking here:

I want to get the composition right. I’ve got no time to be the great master of anything; I just have to get the picture. Also, I always worried about exposure – I didn’t want to take a picture that was underexposed and then be killed. There are so many things going on, and I’ve always put my hands into fate. But you’ve got to stand up, and you’ve got to get the composition right. I just gambled and gambled, all the time.

I’m definitely trying to get information across, but within a formal composition. And I’ve got to do that in a split second; I’m dealing with 125th of a second – it’s the blink of an eyelid. Most people have a bit longer than that to make a decision, so I’ve got to be bloody quick. I try to foresee things, and always be two steps ahead. My mind has been sharpened like a pencil, like a needle. I’m like a surgeon in a way: I have the sharpest scalpel in the world, and it’s my brain.

I’m always under pressure, always worried, and in those days, you had to wait weeks to bring the film back to England and have it processed. Can you imagine the discipline? I had such discipline, and I’ve still got it. I had a great respect for film and knew you mustn’t spoil or abuse it. I always used to go to Vietnam with thirty rolls of Tri-X film – nothing more, nothing less.

Photographing the Story

I used to concentrate on the battle, on the soldiers in the front, but of course, that was never the true story. The true story for me later developed into the suffering of civilians.

McCullin has only set up a photograph once and that was his famous image of the dead Viet Cong soldier surrounded by his modest possessions.

I came across the body of a young Viet Cong soldier. Some American soldiers were abusing him verbally and stealing his things as souvenirs. It upset me – if this man was brave enough to fight for the freedom of his country, he should have respect. I posed him with his few possessions for a purpose, for a reason, to make a statement. You see, I’d developed a mind by then, I was my own man and I’d got attitudes. I felt I had a kind of puritanical obligation to give this dead man a voice.

McCullin always stayed true to his methods of working. He would often return to England to process and print his film before sending it to editors, while other photographers would continue shooting and send their films back instead. The advantage to his method is that it would remove him from danger at the right time, with many others perishing while trying to capture the action, after staying in the field too long.

Many critics have suggested that McCullin “feels” his images, rather than takes them, which is something agrees with:

Photography isn’t about just pushing that button. It’s about the experience of being there. I bring to my photography the principles of my mind and what I’m trying to do. I’m bringing the direction of who I am and what I’ve seen. I’m bringing my identity to it with my printing and my composition.

Editing his Work

When it came to editing his work, McCullin was ruthless and would only show his best photos, which was rarely the case for other photojournalists of the time.

I always gave the art department a very tight edit, and they never asked for more. They trusted me – after all, I had risked my life on many occasions for them and I’d earned the right to make my own selection.

However, McCullin has admitted to overlooking his iconic Vietnam image, the close-up of a shell-shocked American soldier. When he arrived back to the UK, he was exhausted and with his deadline fast approaching rushed the editing process. “I was too busy looking for the action pictures and missed it. It taught me a lesson.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson once compared McCullin’s photos to the work of painter Goya, who was known for his dark and mysterious creations, but McCullin dismisses the comparison to the artist or any art for that matter.

I have a strong creative desire but I’m not trying to be an artist. I don’t need titles. I hate the title, ‘artist’. I just describe myself as a photographer. I have a good nose for news. It’s about knowing your trade. There’s no confusion in my approach. I’m not wide-eyed, I’m precise, direct. I work to a set of rules, ethics. I don’t like wasting film. I have respect for film.

I’m not an artist, even though I compose my pictures as best I can. In a split second under fire, some people wouldn’t bother, but I’ve stood up in battles and put up the exposure meter first because I’m not going to get killed for an underexposed negative.

Don McCullin’s Influences

McCullin names Alfred Stieglitz as his biggest influence, followed by Edward Steichen and Josef Sudek.

The first photographer whose work I fell in love with was Alfred Stieglitz. He had a discipline that I admired, which was not to let anything out of the darkroom that wasn’t the best.

Also, I have always loved Josef Sudek’s work. I put him on the top of my list, even though I weaned myself on Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. Sudek lost his right arm while in the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War and had to load his film with one hand, sometimes using his teeth. War must have made him feel he had to turn his disadvantage into the poetically beautiful: photographs of condensation on the windows of his Prague flat, flowers, the tree in his garden in winter. He was a bit like me in one way, because he started experimenting with darkness, and in the end, his pictures looked as if he had just got a felt-tip pen and made a square of black. He was entrenched in that moment of darkness, like a wave of his past coming back to him.

The following are also named as influences in various interviews with McCullin over the years: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Frederick Evans, Peter Henry Emerson, Henry Peach Robinson, Francis Frith, and David Roberts.

What Camera Does Don McCullin Use?

McCullin is a film man and loves Kodak Tri-X. In 2012 he started using Canon 5D cameras and continues to use them alongside his medium and large format film cameras today.

For more than 50 years, McCullin primarily used 35mm film cameras with his favorite focal lengths: 28mm and 135mm. He always had two cameras with him: one with the 28mm and the other with the 135mm. Along with his trusty Gossen Lunasix 3 lightmeter around his neck.

For his recent work, the 28mm has been replaced by the 35mm.

Although McCullin has used Ilford films in the past, he is a Kodak Tri-X man through and through. 90% of the time he would rate his film at standard box speed (either ASA 320/400) unless he was shooting in low light then he would rate his film at 800 or 1600 instead. To produce a useable negative, he would then push (overdevelop) his film in the development process to produce useable negatives, resulted in an increase in grain giving images a rawness that adds to their authenticity.

Camera History

McCullin started off using a Rolleicord in the early ‘60s. He changed format to 35mm and Nikon F cameras around the mid-’60s. The Nikon F is famous for saving McCullin’s life when he was on assignment in Cambodia. When the Vietnamese forces he was accompanying were ambushed, the Nikon blocked a bullet aimed at McCullin’s head from a sniper attack.

In the ‘70s, McCullin switched to Olympus, starting with the OM1 and later the OM2. The OM-1 caused a sensation in the photography world when it was launched in 1973 because it represented a massive improvement in 35mm SLR design. The camera was more compact and lighter than the competition, giving photographers more freedom out in the field without a reduction in quality. To read more about McCullin’s experience of Olympus, you can read the article here.

First Steps into Digital

McCullin continued to use Olympus and Rolleiflex cameras until he switched to Canon digital cameras in 2012. Here’s a great insight McCullin’s process from an interview with Canon in 2016:

Very often looking ‘down there’ [he moves as if to mimic looking through his old Rollei] works better because people are less aware. I’ll give you an example of that: I went to the Southern Omo valley in Africa a few years ago with two cameras; a medium format and a 35mm. The moment I held the 35mm camera to my face the people wanted money. So, I popped a wide-angle lens on the medium format, looked down to focus so they thought I wasn’t actually taking a picture, and got them all for free…

Seeking the Light and Canon

The 2012 promotional video, Seeking the Light sponsored by Canon shows Don making his journey into the world of digital photography armed with two Canon 5D Mark III cameras and his favored 28mm and 135mm lenses.

It should be noted that in other documentaries such as Don McCullin: Kolkata and Don McCullin: Looking for England he used a Canon 35mm F1.4L II and the Canon 135mm F2L lenses with two Canon 5D Mark IV’s.

Since being introduced to the world of digital photography McCullin has used the cameras on a few of his more recent projects including Syria, India, and Iraq. However, it should be noted that his landscape photos are still shot using medium-format (Mamiya Super 23) and larger format cameras such as the Linhof Technika.

Digital cameras are extraordinary. I have a dark room and I still process film, but digital photography can be a totally lying kind of experience, you can move anything you want … the whole thing can’t be trusted really.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2015, McCullin recalls one of his best experiences, standing on Hadrian’s Wall in the middle of a blizzard, “If I’d have used a digital camera, I would have made that look attractive, but I wanted you to get the feeling that it was cold and lonely.”

Recommended Don McCullin Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Don McCullin (2015) *Must Own Book

- Don McCullin: The Landscape (Cape, 2012)

- Don McCullin: In England (Cape, 2007)

Recommended Don McCullin Videos

McCullin

This 2012 Bafta-nominated documentary about Sir Don McCullin reflects on his life and career working as a photographer. McCullin talks openly about his time covering wars in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East as well as photographing Africa and the famine crisis. This is the best documentary on McCullin and a must-watch for all photographers out there.

Sir Don McCullin in Kolkata

This is more of a promotional video by Canon for Canon cameras but it’s still a good watch to see Don work his magic on the streets of Kolkata. If you’ve ever been interested in how the legendary photog goes about his business in the field, then this short video will give you a better idea. You should be able to pick up quite a few tricks by watching this. Okay, so the photos aren’t his best work but seeing the great man practicing his craft is a good enough reason to watch this. I would have preferred him to use two Olympus OM’s loaded with Tri-X but I don’t think Canon would have paid him to do that. Instead of his usual 28mm/135mm setup, he instead opts for a Canon 35mm 1.4L II and a Canon 135mm F2L.

Contact Sheets Volume 1: Don McCullin

In this 13-minute masterclass on photography, McCullin provides commentary on some of his famous photographs and how he arrived at the decisive moment for each photo. You’ll find yourself watching and re-watching this video over again to learn from McCullin’s experience. Exploring McCullin’s visual journal provides us with an invaluable insight into his working methods and is another must watch for all photographers.

Looking for England

This BBC documentary first shown in 2019 follows Don McCullin (83 at the time) as he documents the inner cities to seaside towns of England, on a journey in search of his nation. 60 years after his first photos of The Guvnor’s in 1958, Sir Don returns to his old haunts in Bradford, the East End of London, Scarborough, Consett, and Eastbourne. It’s also the first time he has allowed cameras into his darkroom. This is a charming documentary that provides a wonderful insight into the work of Don McCullin.

Available to watch on the BBC only.

Fact Check

With each Photographer profile, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the article.

If there is anything else you would like to add about McCullin’s work, his life, and how he has had an impact on you (or other photographers) then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

The website was put together by photographers for photographers, so we can all learn from masters like Sir Don McCullin. The more links we have to us, the easier it will be for others to find the website.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Recommended Links

Don McCullin Official Website

NY Times, Don McCullin Is a War Photographer. Just Don’t Call Him an Artist

Don McCullin: The Interview, Tate Museum

Sources

Unreasonable Behaviour: An Autobiography, Vintage, 2002

Shaped by War, Cape, 2010

The Impossible Peace, Cape, 2012

Don McCullin: The New Definitive Edition, 2015

Contact’s Volume 1: Don McCullin, 2005

McCullin Documentary, Morris/Morris, 2012

Seeking the Light, Canon, 2012

John Tusa Interview with Don McCullin, BBC Radio, 2013

Irreconcilable Truths, Canon, 2016

Sir Don McCullin in Kolkata, Canon, 2017

Looking for England, BBC, 2019

Don McCullin Biography, Hamilton Gallery

The extender Interview: Don McCullin, Hotshoe Magazine, 2016

Don McCullin talks war and peace, British Journal of Photography, 2019

I remember: Don McCullin, Readers Digest

Don McCullin Interview, Apollo Arts, 2020