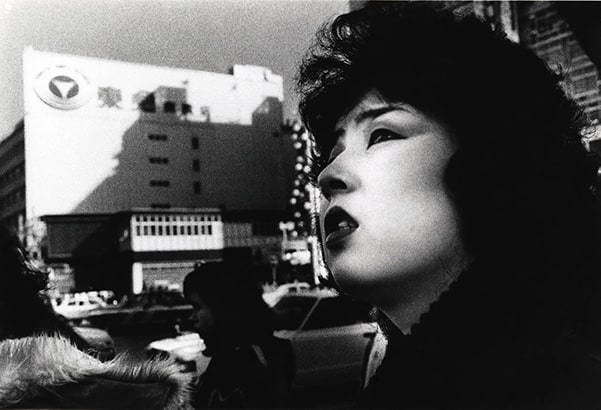

Daido Moriyama is long regarded as Japan’s greatest living photographer. The prolific shooter is known for his gritty black and white images of post-war Japan and his unique snapshot style of street photography, which has influenced photographers around the world.

Related: 40 Daido Moriyama Quotes to Improve your Street Photography

Table of Contents

Diado Moriyama Biography

Moriyama grew up in Osaka, Japan. After becoming a freelance graphic designer at the age of 20, Moriyama fell into photography by chance when he picked up a print from a local photography studio:

I was really struck by the atmosphere. Design was desk-bound, but this felt active… groovy. I wasn’t interested in taking pictures, I just liked the feel of the photographic world.

Not long after, Daido purchased a Canon 4SB from a friend and began shooting the streets of Osaka.

In those days, you never saw anyone out on the streets with a camera around their neck. I felt like I was doing something really way out and original. I never imagined I’d end up doing it – essentially living on the streets – for the next few decades.

In the late 50s, he studied photography under Takeji Iwamiya, then in 1961, he moved to Tokyo and worked as an assistant for photographer Eikoh Hosoe for three years.

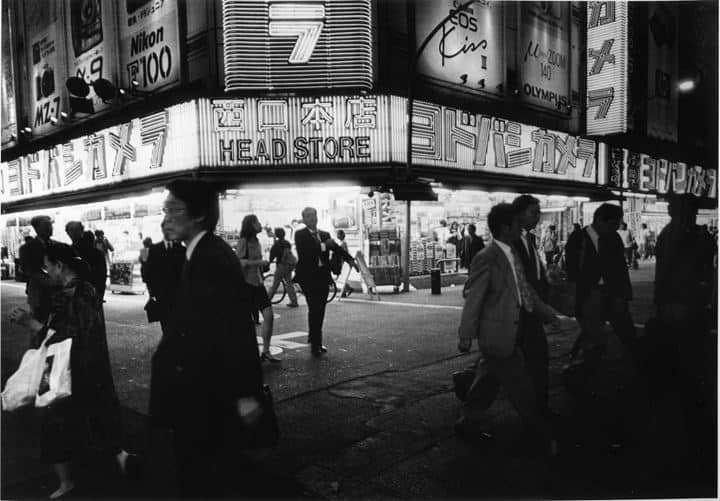

In 1964, Daidō began to work on his own projects. His early work showed the darker side of urban life in Tokyo. Moriyama’s interest in hidden Tokyo, attracted him to subjects such as yakuza gangsters, nightclubs, and prostitutes.

Provoke Magazine

In the late ‘60s, Moriyama became a founding member of Provoke, an avant-garde photography magazine published between 1969 and 1970. The magazine is now regarded as a seminal work of post-war Japanese art.

Provoke was formed by a small group of left-wing photographers, who used the magazine as a platform to redefine Japanese photography to mimic the time while chronicling the nation’s political and social turmoil. Not coincidentally, the magazine’s subtitle read ‘provocative documents for the sake of thought’.

Japan was moving fast, and we wanted to reflect that in our work.

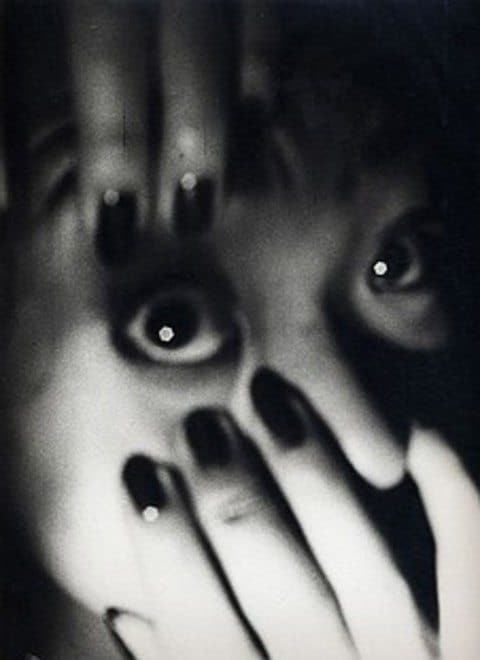

While Japanese art and photography had been all about beauty and precision, the work that came out of Provoke turned this idea on its head. What the photographers had in common was the use of a style that intentionally moved away from what was conventionally accepted at the time by the photographic world, and was identified with the expression “are, bure, boke” (rough, blurred and out-of-focus).

Moriyama’s photos featured in two out of the three issues of the magazine, yet he remains the most influential of the photographers involved in the project.

Snapshot Photography

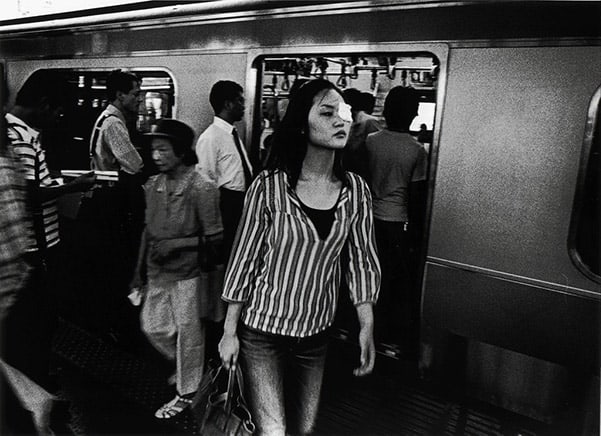

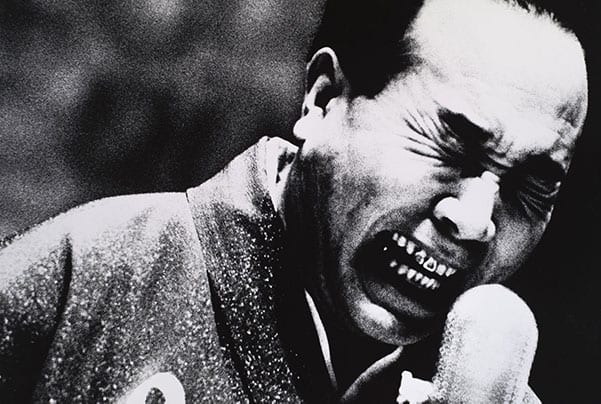

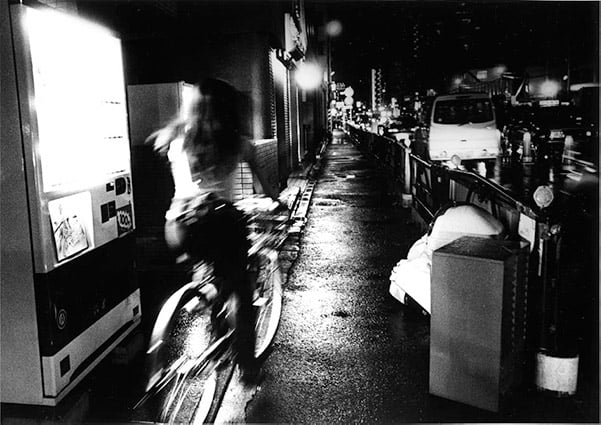

Moriyama’s aesthetic and his method of taking quick snapshots without looking through the viewfinder are two distinctive features of his work. His photographs experiment with light, shade, and abstraction while allowing for serendipity and accident.

My photos are often out of focus, rough, streaky, warped, etc. But if you think about it, a normal human being will in one day perceive an infinite number of images, and some of them are focused upon, others are barely seen out of the corner of one’s eye.

Moriyama’s images are also characterized by the lack of composition and busy subject, which give the impression that something is about to occur within the frame. Largely shot with a small hand-held automatic camera, Moriyama’s work is often partially out of focus or shot on a diagonal composition, adding rawness and energy to his urgent photographic style.

He followed what is known as “Wabi-Sabi”, the Japanese term for beauty in imperfection. While his work looks flawed to many, these imperfections are used to portray a sense of reality, highlighting the beauty in the imperfection: imperfect people living in an imperfect society.

Stray Dog

One of Moriyama’s most famous photographs is of a stray dog he encountered in Aomari. The photo was taken in 1971 and has become a visual metaphor for both himself roaming the streets hunting for his next photo, and the uncertain and quickly changing times of 1970s Japan.

I took this photograph when I went to Misawa in Aomori to work for a camera magazine. I stepped out of the hotel in the morning to go out for a photoshoot, the dog was just there. So, I immediately took several pictures.

I realized later in the darkroom when I printed the image how amazing the dog’s expression is. Snapshots are all about an instant moment and this dog instantly became a part of me. I am actually honored to be compared with that dog.

If you watch any Daido Moriyama documentary (see recommendations below) you’ll see him walking the streets, without a destination. He goes wherever his mood and instincts take him, photographing whatever he finds interesting.

I basically walk quite fast. I like taking snapshots in the movement of both myself and the outside world. When I walk around, I probably look like a street dog because after walking around the main roads, I keep wandering around the back streets.

Photo Journal

Moriyama uses the camera as a photographic diary with many shots taken in motion, giving his photos a sense of narrative and time. His photographs are a record of his wanderings in which the journey is as important as the destination. He has cited Jack Kerouac’s On the Road as one of his major influences on his style and work.

When I go out into the city, I have no plan. I walk down one street, and when I am drawn to turn the corner into another, I do. Really, I am like a dog: I decide where to go by the smell of things, and when I am tired, I stop.

Farewell Photography

In 1972, Moriyama published Shashin yo Sayonara, translated into English as Farewell Photography. The book demonstrated his revolutionary approach and contempt for conformity in photography.

Clarity isn’t what photography is about.

While photographers of the time were doing well-composed, beautifully toned pictures, Moriyama instead experimented with an anti-photographic style. His grainy, out of focus, contrasty images, often unbalanced and even casually framed, were a middle finger at what was traditionally considered a good photograph.

Later Work

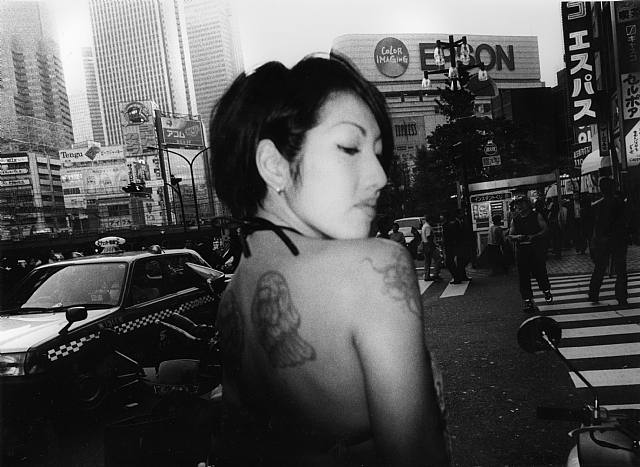

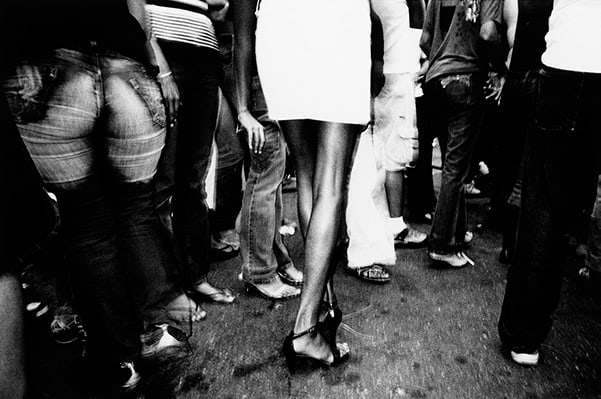

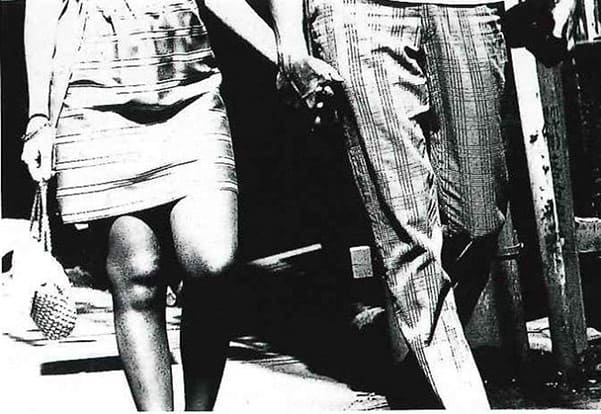

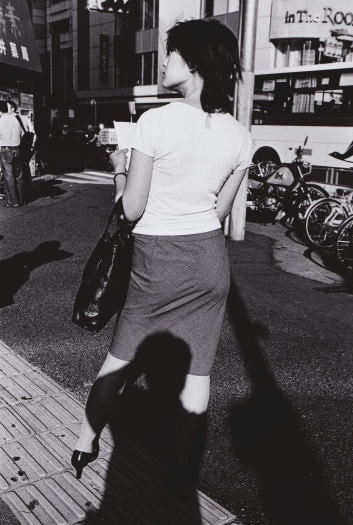

Among the most successful series made later in his career was his 1987 project Tights. Tights comprised of a series of close-up photographs of women’s legs in fishnet tights. Moriyama placed the lens so close to the subject that it’s difficult to distinguish the lines of the legs, making the images more of a visual study in form and texture, along with an undeniable erotic subtext.

Daidō Moriyama has spent his life obsessively photographing the dirty stairwells, neon signs, and salarymen of Japan’s capital in gritty black and white. He would continue the themes of urban mystery and memory throughout his career and continues to roam and snap the streets of Tokyo today.

He has been given awards over his career and gained a cult-like following of fans who are inspired by the dark, contrasty style he helped create. The pioneering photographer’s visual signature style is as recognizable as any. The Picasso of the photography world, Moriyama wasn’t afraid to challenge the status quo and go against photographic tradition.

Moriyama typically presents his work in the form of photobooks and has published an incredible 150 books since 1968. His work has been exhibited in the most respected galleries including Tate Modern in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Influences

Moriyama’s influences include photographers Eikoh Hosoe, Shomei Tomatsu, Weegee and Eugene Atget, artist Andy Warhol and writers Yukio Mishima and Jack Kerouac (notably his book: On the Road).

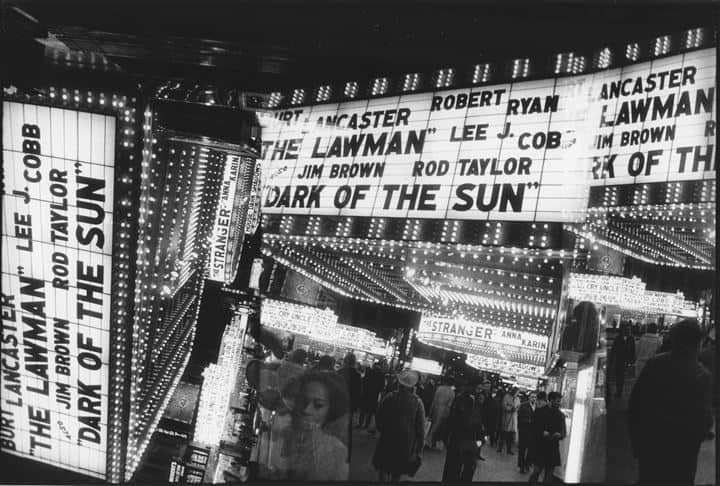

His biggest influence perhaps though was William Klein. Daido’s style and attitude mirrored that of Klein’s own gritty, black and white, confrontational photographs of New York in the ‘50s and the American’s disinterest in traditional photography rules.

I was so touched and provoked by Klein’s photo book, that I spent all my time on the streets of Shinjuku [one of Tokyo’s wards], mixing myself in with the noise and the crowds, doing nothing except clicking, with abandon, the shutter of the camera.

Moriyama’s style is so closely linked to Klein’s that in 2012 they teamed up for a double retrospective titled “William Klein + Daidō Moriyama”. The exhibition at the Tate showcased the contrasting environment and personality of Klein’s New York and Moriyama’s Tokyo.

Photography Style

- Gritty black and white, grainy

- Out of Focus, blurry

- Extreme contrast

- Chiaroscuro (dark, harsh spotlighting, mysterious backgrounds)

- Snapshots and fragments

- Sometimes erotic

Getting the Daido Moriyama Look

Moriyama is known primarily for his black and white work, although recently he has been experimenting with color. His images photographs are known to be in-your-face and have a gritty rawness about them, which are high in contrast and grain.

Editor Note: Producing high-quality content takes time (sometimes up to 2 weeks per article) and money. Sharing the website or linking back to us costs absolutely nothing. To show your appreciation, I would be extremely grateful if you could share the website through social media or photography forums, or even link back to Photogpedia on your own blog or portfolio website (every link counts). Thank you for your support.

Daido’s photos are imperfect by traditional standards, but those same imperfections are what give his photos value and interest.

Moriyama defines a snapshot photograph as an “accidental moment”. His snapshots refuse to disclose their exact location but reveal the people and place.

The first thing I always tell anyone who asks me for advice is: Get outside. It’s all about getting out and walking. That’s the first thing. The second thing is, forget everything you’ve learned on the subject of photography for the moment, and just shoot. Take photographs – of anything and everything, whatever catches your eye. Don’t pause to think. That’s the advice I give people…

He often shoots with tilted horizons to express the disconnected nature of society. His photos have blur and imperfections, going against the compositional rules of traditional photography. He mixes a sense of fantasy and erotic mystery into his work too.

Photography is the act of fixing time, not of expressing the world. The camera is an inadequate tool for extracting a vision of the world or of beauty. The photographer who attempts to fit happily into the world by using the traditional perspective of the camera will end up falling into the hole of the idea he has dug for himself. Photography is a medium that only exists by momentarily fixing the discovery and cognition to be encountered in the ceaselessly moving exterior world.

The Hunter

Moriyama is an experienced hunter of photos, capturing images of anonymous passers-by, prostitutes, gangsters and stray dogs on the streets or hidden alleyways of Tokyo (or wherever the road takes him). After more than six decades of shooting, he has his technique down to an art.

Moriyama is a big believer that anything can be made into a photo. He shot a lot of film and isn’t someone afraid to push the shutter, often getting through 36 exposures within a couple of hundred meters. He has never cared much for what Cartier-Bresson described as “the decisive moment”.

For me, photographs are taken in the eye before you’ve even thought what they mean. That’s the reality I’m interested in capturing.

I’ve never felt that I should conform to any particular set of rules.

The Copy of the Copy

He has said that photography has never been anything other than copying, hence why he takes photos of posters and billboards, even when it contains an image by another photographer. He won’t hesitate to publish the photo either. For Moriyama, all he’s doing is making a copy of something that is already a copy.

I’ve even considered doing away with the copyright symbol from my own photo books. Of course, the publishers would object, there’d be all sorts of problems. But basically, I think everyone should be free to copy anything they want to. What else is a photograph but a copy to begin with? When I hear people getting all hot under the collar, making the argument for photographs being original, being “art”, and so on, I always think to myself, “Oh, come on, get real…

Most of my photographs are taken on the street, of objects on the street. I want to capture the relationship between objects and people. I don’t ever think about what people are going to think looking at my photographs. There are many things I can’t control. That viewers see the photographs in a different way is really important, but it doesn’t influence the work. My message enters the image, but I think it’s good if many messages enter the image, not just mine.

Different Perspective

Moriyama states that it’s important to look at subjects from every angle, even if that means going back down the same street in the opposite direction and standing still and waiting for something that interests you to enter the frame.

Most people only take snapshots of things immediately around them in their daily life. Fundamentally that means that they’re not going out of their comfort zone. But out on the city streets, everything you encounter is alien and unknown. That’s what taking snapshot photographs of the city streets is: you’re capturing the alien and unknown.

Moriyama also always returns to the same places: empty dark alleys, the doorway of a strip club, neon signs, overcrowded subway stations. He is not interested in beauty.

Most of my work, whether shot in Japan or abroad, is made on the street. I like to photograph the cities I visit and the people I encounter there. One of my best-known images, a shot of a stray dog taken in 1971, is an example of the kind of thing that catches my eye. But sometimes I want to shoot more erotically charged scenes, such as a woman in tights, or a woman’s lips.

Daido’s Advice for Photographers

Of course, a sharp eye is fundamental. And of course, you have to be alert, sensitive, responsive, at ease in your own body, so that you can react to the stimuli around you immediately. But above all, you have to have desire. That desire the photographer must feel in the instant he takes the shot. If you don’t have desire, you won’t see what’s there. I’m talking about the desire you feel in that moment when you see something that compels you to take your shot – it could be a woman, or anything. Desire is all around us; there’s a huge, limitless supply of it. It’s important to be true to that desire. To take a photograph that is at all interesting or meaningful, you must become one with that desire when you press the shutter button…

To get a better understanding of how Moriyama works, check out the short documentary below.

Daido Moriyama: In Pictures was produced by Tate in 2012 before his joint exhibition with William Klein at the gallery. In this short documentary, we follow Moriyama as he walks the Shinjuku neighborhood in Tokyo with a camera in-hand. This is probably the best documentary presently on Moriyama (well it’s the best I’ve seen anyway.)

What Camera Does Daido Moriyama Use?

Moriyama is perhaps best known for using the Ricoh GR series of cameras which has gained a cult status amongst street photographers. He mainly used the Ricoh GR1s 35mm film camera with a fixed 28mm lens and sometimes a Ricoh GR21 for a wider field of view.

Remember though that the Ricoh GR was only released in 1996. Yes, many photos were shot using the legendary GR but they only accounted for a small percentage of his overall body of work. His famous photos (Stray Dog, Tights, etc) were shot before 1996 and the Ricoh’s release.

Here are just a few of the cameras he used before the GR series: Canon 4SB (his first camera), Nikon S2 with a 25/4, Rolleiflex, Minolta Autocord, Pentax Spotmatic, Minolta SR-2, Minolta SR-T 101 and Olympus Pen W.

Daido currently uses a digital camera and edits his images in Silver Efex Pro to match the look of film. In 2018, he used a tiny Sony RX0 without an LCD screen. Before this, he used a cheap Nikon Nikon S9100. He has played around with the Ricoh GR digital cameras too but preferred the Nikon with its zoom function for its flexibility.

Fuji sponsored one of his recent projects in Hong Kong and gave him a Fuji X10 to use.

Capturing the Image

Moriyama will shoot with anything. He has used a lot of cameras, and when he gets bored of them, or they stop working, he sells them (or gives them away.) The lighter the better.

He claims to have never bought a camera for himself; all the cameras he uses have been given to him. He doesn’t concern himself with cameras, if the camera suits his style of shooting, he’ll use it. To Moriyama, a camera is just a tool.

For Moriyama’s snapshot style of photography, the camera is used to capture the image only and you then make the photograph is made in the editing process.

The best cameras for Daido’s style of photography (as of 2021) are the Sony RX100, Canon G7X, Fuji X10, Nikon Coolpix A, Fuji X100 and Ricoh GR-D (if you like dust on your sensor.) Then again, any camera will do just fine (including the one you own right now.)

Daido’s message is one that we all know, but sometimes forget: the camera captures the photo, the photographer makes the photo. A camera is a tool, no different to a pen used by writers or a brush by painters.

Camera Settings for the Daidō Moriyama Look?

Moriyama’s photos are made in the post-processing stage. He captures the image (or snapshot) on the street and then makes the photo in the darkroom (or in Silver Efex today.)

When shooting it’s important to stay free and to shoot instinctively (try not to think about what you’re doing and just shoot.) Everything you’ve been taught or learned about photography, forget about it. Imagine you’re a 10-year-old and picking up a camera for the first time. The best photos come from accidents. Daido isn’t opposed to cropping an image to get what he wants either.

Using 35mm Film

When it comes to film, Moriyama would always shoot Kodak Tri-X pushed to 1600 ASA, both day and night.

“Monochrome is stimulating and is very erotic. Sometimes my heart is beating fast when I see a black and white world in the developer. I don’t deny digital or color…I use them sometimes; however, I have decided to keep using TRI-X until it’s discontinued.”

Moriyama would underexpose his negatives and then overdevelop it in the darkroom (typically he would push by a couple of stops). Load your camera with a roll of Kodak Tri-X 400 and set the ASA to 1600.

His developer of choice is Kodak D-76 in higher temperatures. I believe he’s also quite rough when agitating the film, to give an increase in grain. This would result in a loss of detail but a massive gain in character. Images would appear extremely high contrast, with exaggerated shadows and blown-out highlights.

The real key to the Moriyama look is in his printing. He has often said that even he can’t match earlier prints and professional printers haven’t even been able to duplicate the look either.

Using Digital

Work in either program or aperture priority mode (the less you think about the better). Use auto-focus and let the camera do the work for you. Single point (center) and matrix metering.

Set your aperture to F5.6 or F8 for daytime, lower this to F2.8 or F4 for night shooting. Ensure your camera is set to RAW + JPEG and turn off image review (forget about looking at the screen after every shot.)

Change your JPEG settings from color to monochrome/black and white. Increase contrast to maximum and bump up the sharpness (you’re still shooting RAW, so don’t worry too much.)

Set your ISO to Auto-ISO (maximum of 6400). Set your cameras minimum shutter speed to 1/30. Finally, set your exposure compensation to around -0.3 to preserve the highlights.

Also, don’t worry about everything being in focus or even sharp – that isn’t the Moriyama way. Just go out and enjoy hunting for images with no expectations.

Don’t look at the back of your camera (chimp). Wait until you get back home before reviewing your images.

Post-Processing

Daido and his assistant use Silver Efex Pro to post-process his work now. I recommend using Nik collection Tri-X preset and then adjusting the contrast and effect strength to your liking.

If you’re working in Lightroom, then here’s what I typically do:

- Push the blacks

- Push the whites (limited grey)

- Increase contrast to maximum

- Add grain (size and roughness)

Other Daido Moriyama Resources

Recommended Daido Moriyama Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Daidō Moriyama: The World through My Eyes (2010)

- How I Take Photographs by Daido Moriyama (2019)

- Daidō Moriyama: Labyrinth (2012)

Daido Moriyama Videos

Daidō Moriyama: Near Equal (2001)

This 90-minute documentary from back in 2001 is probably the most comprehensive look at the life and career of Moriyama. Although it’s a little slow out times, it does provide an insight into his work and shooting style. This Definitely worth watching if you’re a fan of his photography.

Daidō Moriyama – The Mighty Power (2012)

The Mighty Power was made when Daidō was in Hong Kong for his first solo exhibition in 2012. Despite the documentary film only being six minutes, the short by Ringo Tang still provides enough wisdom from the master photographer to justify watching.

More Daido Moriyama Photos

View more Moriyama Photos here and here

Fact Check

With every profile we produce, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right or is factually incorrect, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there’s anything else, you would like to add about Moriyama’s work or photography techniques then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through the usual social media channels.

The website was put together by photographers for photographers, so we can all learn from master photographers like Daido Moriyama.

The more links we have to us, the easier it will be for others to find the website.

Finally, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram and Twitter to keep up to date with our latest posts.

Recommended Daido Moriyama Links

To learn more about Daido Moriyama’s work, visit the Official Daido Moriyama website.

Sources

Daido Moriyama Photographs His Beloved Shinjuku, Theme Magazine, 2005

Street Photography Advice, PDNonline

Daidō Moriyama: The Shock From Outside, Aperture, 2010

In Light and Shadow, Simon Baker, Daido Moriyama, 2012

Daido Moriyama And the Cultural Landscape of Post-War Japan, Time, 2012

How to Take Photographs like Daidō Moriyama, Artsy, July 2019

Daidō Moriyama: The World through My Eyes, Skira, 2010

Daidō Moriyama: Labyrinth, Aperture, 2012

Memories of a Dog, CITIC Press, 2018

How I Take Photos, Laurence King Publishing, 2019

Near Equal Moriyama Daido, BBB, 2001

Daido Moriyama: In Pictures, Tate Museum, 2012

The Mighty Power, Ringo Tang, 2012