Bill Brandt is regarded as one of the most important photographers of the 20th century. He is best known for his surrealist influenced nudes and his photos of London during the Blitz.

During his five-decade career, Brandt produced important work in all the major genres of photography: social documentary, landscape, nude, and portrait.

While he pursued several subjects throughout his lifetime, Brandt tended to focus on one genre for an extended period before moving on to the next one.

His witty pictures of social life in London during the 1930s and his compassionate photographs during the depression are some of his most memorable images.

Both a visual poet and a historian, his pictures capture and preserve a world that has disappeared forever.

In this article, we will aim to provide an introduction to Brandt’s work, with particular emphasis on his photography style and working methods.

Related: 28 Bill Brandt Quotes to Learn From

Editor note: If you enjoy our Bill Brandt article and find it helpful, then we would be grateful if you could share it with other photographers through your own blog, social media and forums.

The photographer must first have seen his subject or some aspect of his subject as something transcending the ordinary. It is part of the photographer’s job to see more intensely than most people do. He must have and keep with him something of the receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time or of the traveler who enters a strange country… they carry within themselves a sense of wonder.

Bill Brandt

Table of Contents

Bill Brandt Biography

Name: Bill Brandt (born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt)

Nationality: British

Genre: Documentary, Photojournalism, Nude, Landscape, Portrait

Born: 2nd May 1904 – Hamburg, Germany

Died: 20th December 1983 (79 years old) – London, England

Early Life

Bill Brandt was born in Hamburg, Germany to a German mother and British father. His childhood was mostly spent in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

At the age of 16, he contracted tuberculosis and spent six years recovering in a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. It was during this time that he first took up photography.

After being sent to Vienna for lung analysis in 1927 he met the Austrian writer, Dr. Eugenie Schwarzwald. She suggested that he should pursue a career in photography.

Photography Career

Brandt followed her advice and secured an apprenticeship with the Austrian photographer Grete Kolliner.

While working at the studio, Brandt took the portrait of Ezra Pound. The American poet was impressed with the image and recommended that Brandt go to Paris to work under Man Ray.

Brandt arrived in Paris to begin a three-month apprenticeship at the Man Ray Studio in 1929.

I had the good fortune to start my career in Paris in 1929. For any young photographer at that time, Paris was the centre of the world. Those were the exciting early days when the French poets and surrealists recognized the possibilities of photography.

Bill Brandt

Although there was little direct teaching from Man Ray, Brandt was able to absorb the new developments in photography and various art movements in Paris.

Brassai, Kertesz and Cartier-Bresson were all working in Paris, as well as Man Ray. Man Ray, the most original photographer of them all, had just invented the new techniques of rayographs and solarisation. I was a pupil in his studio and learned much from his experiments.

Bill Brandt

Moving to England and Photojournalism

In 1931, Brandt moved to England at the age of 27 to work as a freelance photographer.

He decided to pursue a career in photojournalism, a profession still in its infancy. However, Brandt was a photojournalist with a difference. For under the tutelage of Man Ray, Brandt had developed his own moody, surreal style.

Brandt began his career by documenting British life and the contrasts he saw in it.

He used his family ties to document the wealthy alongside the poor. Many of these images were staged, with family and friends acting out the scenes he wished to create.

After several years of working on the project, he published his first book, The English at Home in 1936.

The extreme social contrast during those years before the war was, visually, very inspiring for me. I started by photographing in London, the West End, the suburbs, the slums.

Bill Brandt

Brandt’s documentary work occurred at the same time as the rise of the picture press in England and as a result, his photo series became synonymous with British life between wars.

I photographed pubs, common lodging houses at night, theatres, Turkish baths, prisons and people in their bedrooms. London has changed so much that some of these pictures now have a period charm almost of another century.

Bill Brandt

The Industrial Depression

After several years of working in London, Brandt decided to travel to the north of England, where he photographed coal-miners during the industrial depression.

My most successful picture of the series, probably because it was symbolic of this time of mass unemployment, was a loose-coal searcher in East Durham, going home in the evening. He was pushing his bicycle along a footpath through a desolate waste-land between Hebburn and Jarrow. Loaded on the crossbar was a sack of small coal, all that he had found after a day’s search on the slag-heaps. I also photographed the Northern towns and interiors of miners’ cottages, with families having their evening meal, or the miners washing themselves in tin-baths, in front of their kitchen fires.

Bill Brandt

London at Night and War Years

In 1938, Brandt published his second book, A Night in London.

For the series, Brandt photographed the streets of London after dark, capturing the eerie beauty of the city.

To light the scenes, he either used street lights or transportable tungsten lights (also known as photo floods).

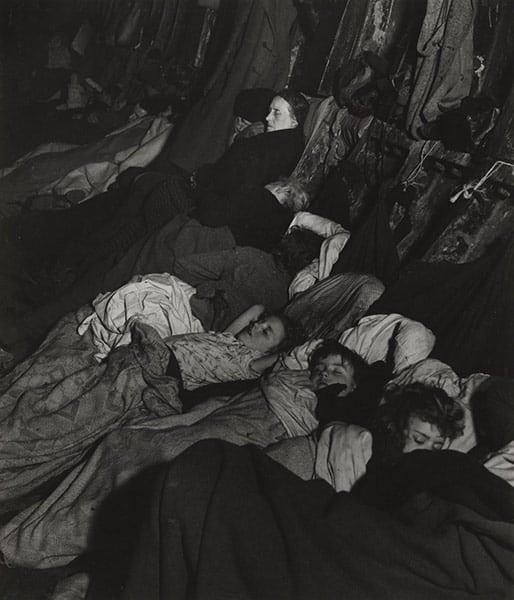

The war years were productive for Brandt. He photographed the empty streets, and the war-ravaged buildings of London during the early Blackouts, and the Blitz.

In 1940, Brandt was commissioned by the government’s Ministry of Information to report on Londoners seeking refuge in underground air-raid shelters.

The assignment produced some of Brandt’s finest work.

At night Brandt visited the overcrowded shelters (tube stations, church crypts, and cellars) and photographed families huddled in cold, uncomfortable spaces.

His use of artificial light and the contrast between shadow and light make these images incredibly powerful.

Post-War Years

After the war, Brandt decided to change his style and gradually moved away from photojournalism. He later reflected:

Towards the end of the war, my style changed completely. I have often been asked why this happened. I think I gradually lost my enthusiasm for reportage. Documentary photography had become fashionable. Everybody was doing it. Besides, my main theme of the past few years had disappeared; England was no longer a country of marked social contrast.

Bill Brandt

The second half of Brandt’s career brought him further acclaim.

His photos were more experimental and characterized by a mysterious and brooding quality that provided a fresh look on some of the most common genres: portraiture, landscape and the nude.

[For] whatever the reason, the poetic trend of photography, which had already excited me in my early Paris days, began to fascinate me again. it seemed to me that there were wide fields still unexplored. I began to photograph nudes, portraits, and landscapes.

Bill Brandt

Brandt returned to portrait photography. Over the next three decades, his portraits of artists, writers, musicians and actors were published in Harper’s Bazaar.

From 1945 onwards, Brandt took a series of landscape photographs for Lilliput magazine. The images were accompanied by excerpts from famous texts by British writers including Charles Dickens and Emily Brönte.

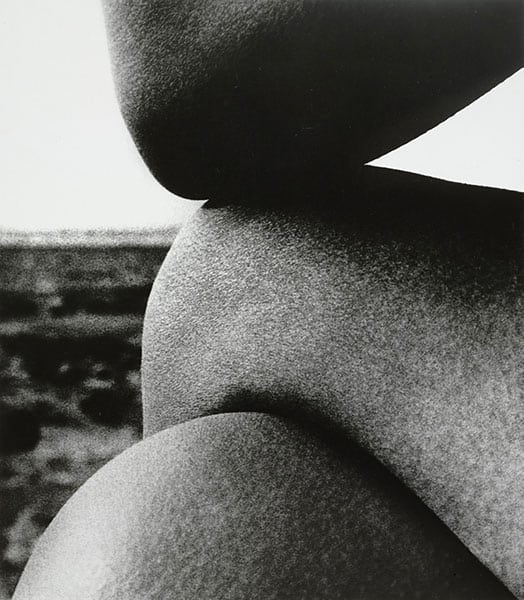

Bill Brandt’s Nude Photography

Brandt’s most important images from this period though are the series of nudes taken between 1945 and 1961, which are considered to be his crowning artistic achievement.

Influenced by the work of Man Ray, Henry Moore, and Picasso, Brandt’s early nude photos were taken typically in interiors and studios using an old Kodak camera with an extremely wide-angle lens (see Brandt’s camera section below).

His later nudes, which became increasingly more abstract and surreal, were taken on beaches of Sussex and northern and southern France.

Brandt’s Later Years

In the 1970s and 1980s, Brandt began to explore new processes.

He created three-dimensional collages using rocks found on the beach, and started photographing in color for the first time in his career.

His later work was more experimental, and he drew heavily on his interest in surrealism art, and the influence of Man Ray’s work in the 1920s.

When you have done everything inside you, you cannot carry on unless you repeat yourself, and that’s not very interesting.

Bill Brandt

Brandt’s collages and color photographs were exhibited in London in the mid-1970s, and again ten years after his death in 1992.

His work from this period was never embraced by critics and is rarely included in retrospectives of his work.

Brandt spent his remaining years reissuing his work in a series of books and teaching photography at the Royal College of Art.

Bill Brandt died in London on 20 December 1983 at the age of 79.

Brandt’s Photography Legacy

Brandt’s work was published in magazines domestically and abroad including Lilliput, Picture Post and Harper’s Bazaar.

His books, which include A Night in London (1938), Camera in London (1948) and Perspective of Nudes (1961) are among the most influential photo books of the period.

Brandt had his first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969. His work has since been the subject of major retrospectives in both the UK and abroad.

His photography is held in several public collections, including the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Brandt’s work has influenced many photographers including Robert Frank, Sir Don McCullin, David Bailey and Roger Mayne.

In 1984, Bill Brandt was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum. He received an honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art in London and was also named an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain.

Bill Brandt’s Style

- Black and white, contrasty

- Moody, atmospheric

- Dramatic, haunting

- Stark light, and use of shadows

- Mysterious, ambiguous

- Surreal, dream-like

Bill Brandt’s Working Methods

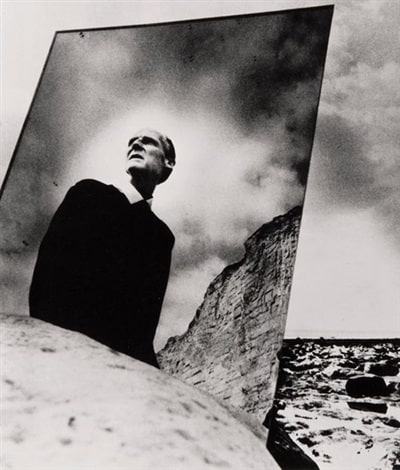

Landscape Photography

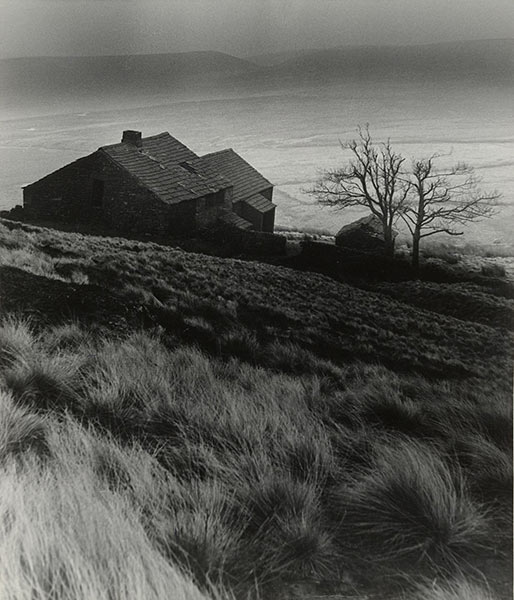

Bill Brandt’s landscape photos have a mysterious brooding beauty that is unique, yet widely imitated. He often visited the same place many times before capturing his image. Below he explains his process and the importance of patience:

To be able to take pictures of a landscape I have to become obsessed with a particular scene. Sometimes I feel that I have been to a place long ago, and must try to recapture what I remember. When I have found a landscape which I want to photograph, I wait for the right season, the right weather, and right time of day or night, to get the picture which I know to be there.

One of my favourite pictures of this time is Top Withens on the Yorkshire Moors. I was then trying to photograph the country which had inspired Emily Bronte. I went to the West Riding in summer, but there were tourists and it seemed quite the wrong time of the year. I liked it better, misty, rainy and lonely in November. But I was not satisfied until I saw it again in February. I took the picture just after a hailstorm when a high wind was blowing over the moors.

Bill Brandt

Nude Photography

Brandt focused on nudes for over three decades and considers it the climax of his creative photography and the most satisfying of his work.

He began experimenting with nude photography in the late 1930s, although he didn’t publish any of these photos until 1961 with the release of his book Perspective of Nudes.

In 1944, Brandt purchased a mahogany and brass camera by Kodak with a Zeiss Protar wide-angle lens that gave his nude photographs an “altered perspective and a less conventional image.”

By using this antiquated equipment he was able to produce an image where the human form was heavily distorted and viewed in an unrealistically deep perspective.

In 1977, Brandt began a second series of nudes, which appeared along with some earlier photographs in the book Nudes 1945-1980 (1981).

His early work featured naked models in domestic interiors and on the beaches of East Sussex and northern and southern France. While his later, more experimental and abstract nude work, was shot mainly in the Mediterranean.

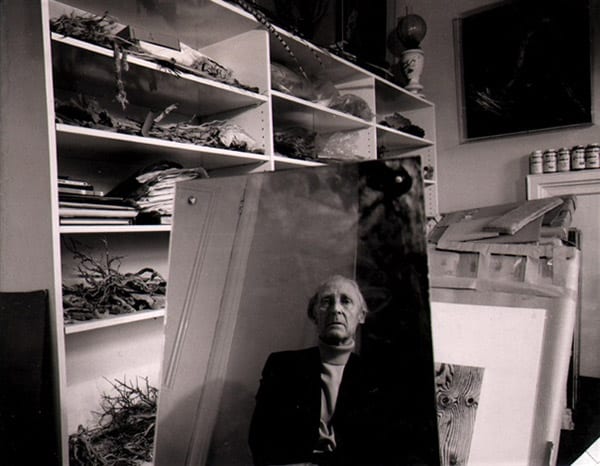

Portrait Photography

Although Brandt’s photography career began with his portrait of Ezra Pound in 1928, he didn’t return to the genre until the 1940s.

Over the next 40 years, he took portraits of writers, actors, musicians and painters for Lilliput, Harper’s Bazaar and Picture Post.

Brandt liked to photograph his subjects in their homes or their own surroundings. He tended to avoid isolating his sitter’s face or focus on their expression. He also never placed them in the center of the frame.

I always take portraits in my sitter’s own surroundings. I concentrate very much on the picture as a whole and leave the sitter rather to himself. I hardly talk and barely look at him. This often seems to make people forget what is going on and any affected or self-conscious expression usually disappears. I try to avoid the fleeting expression and vivacity of a snapshot. A composed expression seems to have a more profound likeness. I think a good portrait ought to tell something of the subject’s past and suggest something of his future.

Bill Brandt

The Darkroom

Bill Brandt enjoyed working in the darkroom and liked to experiment, making many prints of the same negative.

It takes a long time to produce a good print.

He wasn’t one for mass production. Each print was an original, printed and finished by Brandt with utmost care.

I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants. He should know by instinct, grounded in experience, what subjects are enhanced by hard or soft, light or dark treatment. But … no amount of toying with shades of print or with printing papers will transform a commonplace photograph into anything other than a commonplace photograph… It is part of the photographer’s job to see more intensely than most people do.

Bill Brandt

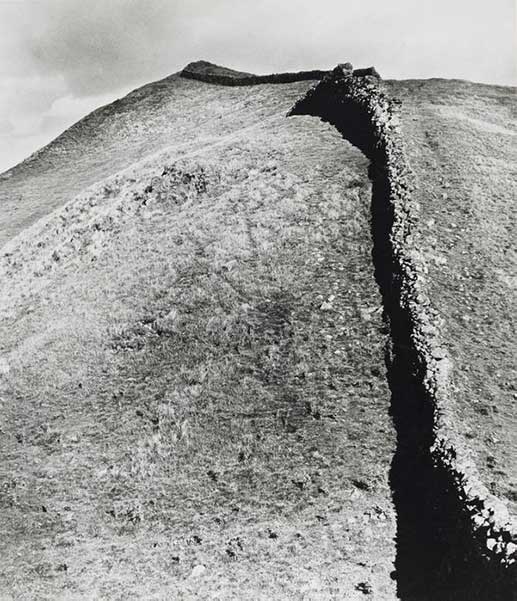

Manipulating the Negative

Brandt liked to manipulate his negatives in the darkroom and quite often cropped an image if it made for a better photograph. This technique can be seen below in his photo of Hadrian’s Wall.

Brandt also liked to combine elements of two negatives into a single print. This was long before the days of Photoshop layers and incredibly innovative for the time.

An example can be seen in his photo, Early Morning on the River (1936).

The image of the seagull, which would have been impossible to photograph with such clarity in low light, was montaged onto a separate photograph of London Bridge and the Thames in fog. Brandt added the morning sun to the image a few years later.

It is the result that counts, no matter how it was achieved. I find the darkroom work most important, as I can finish the composition of a picture only under the enlarger. I do not understand why this is supposed to interfere with the truth. Photographers should follow their own judgment, and not the fads and dictates of others.

Bill Brandt

The Print

The bulk of his prints were made on 8 x 10 inch, single-weight glossy paper. From the mid-1950s, Brandt preferred to print on high contrast paper (typically grade 4 extra hard paper), which allowed him to intensify the black and whites.

Photography is still a very new medium and everything is allowed and everything should be tried. And there are certainly no rules about the printing of a picture. Before 1951, I liked my prints dark and muddy. Now I prefer the very contrasting black-and-white effect. It looks crisper, more dramatic and very different from color photographs.

Bill Brandt

Influences

Brandt worked as an apprentice under Man Ray for three months in 1927. He was heavily influenced by Ray’s experimental style of photography, as well as his use of extreme cropping and grain to create mood and drama.

Brandt greatly admired the work of fellow photographer and close friend Brassaï. In fact, Brandt’s second book, A Night in London (1938) was based on Brassaï’s Paris de Nuit (1933).

His post-war photography, in particular his nude series, was influenced by the film, Citizen Kane and the deep focus technique used by cinematographer Gregg Toland.

When Citizen Kane was first shown, I’d never seen a film in which real rooms were used and you could see everything, the ceiling, and terrific perspective, it was all there. It was quite revolutionary, Citizen Kane, and I was very much inspired by it and I thought: ‘I must take photographs like that.

Bill Brandt

Other influences include the films of Luis Buñuel and Alfred Hitchcock (his early work), Edward Weston’s dune landscape photos from the 1930s, the paintings of Salvadore Dalí, René Magritte, Picasso and Matisse, and the semi-abstract sculptures of Henry Moore.

What Camera Did Bill Brandt Use?

- Hasselblad with Zeiss Biogon 38mm

- Rolleiflex

- Kodak Camera (6.5 x 8.5 plate) with Zeiss Protar 8.5cm/f18 and 11 cm/f18 lenses.

For his photojournalism and portrait work, Brandt used a Rolleiflex. From the 1950s, he used a Hasselblad with a Zeiss Biogon 38mm super wide-angle lens for his landscape and nude photography.

Brandt used 400 ASA black and white film. He tested several 35 mm cameras but didn’t like the size of the viewfinder.

I have tried several models but I find the viewfinder image far too small. I like to see a larger image in order to compose my picture. Composition is essential; good design is inseparable from a good picture. Unfortunately, very few young photographers seem to have any thought or sense of design. They just snap.

Bill Brandt

Kodak Camera and Wide-Angle

In 1945, Brandt picked up a nineteenth-century Kodak camera which he used for his nude photography series.

Feeling frustrated by modern cameras and lenses which seemed designed to imitate human vision and conventional sight, I was looking everywhere for a camera with a very wide angle. One day in a second hand shop, near Covent Garden, I found a 70-year-old wooden Kodak. I was delighted. Like nineteenth-century cameras it had no shutter, and the wide-angle lens, with an aperture as minute as a pinhole, was focused on infinity.

Bill Brandt

Using the fixed-focus camera with a wide-angle lens, allowed him to create heavily distorted images and “see like a mouse, a fish or a fly.”

It had no shutter, the aperture in its wide-angle lens was as small as a pinhole, and it was permanently focused on infinity. It had been used by Scotland Yard for police record work and by auctioneers to make inventories. He loaded the camera with a fast film, and started experimenting. The image on the ground glass was so dim it was useless for pre-planning the picture. The camera had to do its own seeing. Each exposure was a gamble; a picture could never be duplicated. Yet he was immediately excited by the weird results. Perspective was so steep it created an entirely new feeling of picture space.

Other Bill Brandt Resources

Recommended Bill Brandt Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Shadow and Light

- Bill Brandt: Photographs 1928-1983

- Brandt: The Photography of Bill Brandt

- Bill Brandt: A Life

Bill Brandt Videos

BBC Masters of Photography: Bill Brandt (1983)

Bill Brandt Photos

You can view more Bill Brandt Photos on the Museum of Modern Art website.

Recommended Reading

Victoria and Albert Museum, Bill Brandt Section

The Bill Brandt Archive

Bill Brandt Statement on Photography, Camera in London, 1948

Creative Camera Owner Magazine Article

Fact Check

With every profile article, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Bill Brandt’s work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve found this article helpful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through Twitter or any other social media channel.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Related Articles

Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Decisive Moment

Don McCullin: Sleeping with Ghosts

Sources

Museum of Modern Art, Bill Brandt Biography

Victoria and Albert Museum, Bill Brand Archive

International Photography Hall of Fame, Bill Brandt Induction

Bill Brandt: Behind the Camera, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Michael Hoppen Gallery, Bill Brandt Biography

Brandt: The Photography of Bill Brandt

Behind the Camera

Bill Brandt: Photographs 1928-1983

Bill Brandt: A Life, Paul Delany, 2004

Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, 2005

Creative Camera Owner Magazine 1970s

Statement on Photography, Camera in London, 1948

Masters of Photography: Bill Brandt, BBC, 1983