Trent Parke is widely considered one of the most innovative and creative contemporary photographers today.

His photos are known for their dreamlike poetic quality and often use harsh light and deep shadows to add tension and drama.

Although his work is rooted in documentary, his grainy photos are original and quite distinctive, sitting between fiction and reality. Parke’s subjects explore themes of identity, place, and family life in his home country of Australia.

For over thirty years, Parke has been trying to make sense of the world around him, using his camera as a tool for raising deeper critical questions about humanity and life. He is now regarded as one of the best photojournalists working today.

Parke has published several photography books, won national and international awards including four World Press Photo awards, and his photographs have been exhibited around the world. He is also the first Australian to become a full member of Magnum Photo.

Related: 18 Trent Parke Quotes on Projects, Discovery and Life

Table of Contents

Trent Parke Biography

Nationality: Australian

Genre: Documentary, Street

Born: March 20, 1971

Early Life

Trent Parke was born in 1971 and raised in Newcastle, New South Wales. Parke started his photography journey when he was around 12 years old using his mother’s Pentax Spotmatic and the family’s laundry room as a darkroom. When Trent was 13, his mother tragically died from an asthma attack.

There was a point for me that changed everything when I was 13 my mom died of an asthma attack, I was the only one home, it was very sudden, my dad was at his squash night… after that, you question everything, every single thing that’s going on around you. Why am I here? That started me off. Mom had a small darkroom and she took pictures and sent them into the local paper, so I picked up her camera and started taking pictures.

Trent Parke

Moving to Sydney

In 1993, Parke moved to Sydney, and worked as a photojournalist for The Daily Telegraph, then later as a sports photographer for The Australian.

Originally, I was going to be a career cricketer. Photography was just a hobby. But then it became something more and for three years I worked as a newspaper photographer still training, playing cricket and going overseas to play professionally in England.

I started in newspapers as a cadet on the Newcastle Herald and then moved to the Singleton Argus and Cessnock Advertiser in the Hunter Valley. I was the only photographer they had and I did everything: advertising, news, sports, features, the lot! It meant incredibly long hours but it taught me to move quickly, shoot fast, and think on my feet.

When I was offered a job on The Daily Telegraph and made the move to Sydney I thought I would still be able to train and play on weekends. I realized after my first week at work that my sporting career was over – the paper demanded so much. And if I can’t go 100 percent at something, it’s over. I need to live what I do from the moment I get up to the moment I fall asleep (and then to dream about it some more). I didn’t play sport to be average I played to be the best that I could be. It’s not about winning or losing, it’s about making sure you are giving it your best shot with the abilities you have been granted…

I moved to The Australian after a couple of years as their only sports photographer. In sports photography, if you wait until you see something happen, then, by the time you take your shot, the moment has passed. You’ve got to be watching things as they are building in front of you so that you get into position ahead of time. Ten years working as a sports photographer really helps me now because I can sense all the elements of a picture while they are still forming around me.

Trent Parke

Dream/Life

In his spare time, he explored Sydney and began a five-year project, Dream/Life.

The project came as a result of Parke trying to deal with his sense of loneliness at the time. New to the city, he took to the streets with his Leica and began to create a portrait of Sydney unlike anything seen before.

I grew up on the outskirts of Newcastle where the suburbs meet the bush. When I came to Sydney at the age of 21, I left everything behind – all my childhood friends and my best mate – at first I just felt this sense of complete loneliness in the big city. So, I did what I always do: I went out and used my Leica to channel those personal emotions into images.

Trent Parke

His photos were dark and contrasty, while his subjects were often lonely with intense expressions, which mirrored his own feelings at the time.

Dream/Life was really about finding myself and my place in life. I wanted to present a truer version of Sydney – with lots of rain and thunderstorms, and the darker qualities that inhabit the city – not the picture-postcard views the rest of the world sees. But I also wanted to make images that were poetic. Trouble was the city was actually quite ugly in terms of the amount of advertising and visual crap that clutters the streets. I found I could clarify the image by using the harsh Australian sunlight to create deep shadow areas. That searing light that is very much part of Sydney – it just rattles down the streets. So, I used these strong shadows to obliterate a lot of the advertising and make the scenes blacker and more dramatic. I wanted to suggest a dream world. Light does that, changing something every day into something magical.

Trent Parke

Meeting Narelle and Going Independent

In 1999, Parke met fellow photographer and future wife Narelle Autio. No longer feeling alone in the city, he knew Dream/Life had to finally come to an end, and self-published the book in 1999.

Well, I met Narelle [Autio] in 1999. Our eyes met over a lightbox at the newspaper and that was it. And as soon as I met Narelle Dream/Life finished, because emotionally the reason to make pictures had completely changed. I no longer felt alone.

I self-published Dream/Life because, in the end, I wanted complete control of the finished product. It would have been almost impossible to find anyone in Australia to publish a book like that. It cost me about $65,000 and, even though I am never going to make a lot of that money back, I couldn’t begin to place a value on how much it has helped my career.

Trent Parke

Trent and Narelle would often shoot side by side on assignments and would later collaborate on their own projects including the Seventh Wave and Minutes to Midnight.

In late 1999, Parke quit his job at The Australian. After constantly battling higher-ups, and picture editors, Parke decided enough was enough and made the decision to leave and work independently on his own projects.

The Seventh Wave

Parke’s next project Seventh Wave came about after he returned from an assignment with the Australian Cricket team.

In a project spanning two years, Trent and Narelle documented Australian Beach life, visiting famous spots such as Bondi in Sydney, Byron Bay, and Port Macquarie.

I’d done this for many summers and so I had rarely had the opportunity to go to the beach. I remember that day at Freshwater beach very clearly: puffy white clouds, crystal clear water, late afternoon backlighting. One of my childhood friends (nicknamed Wombat) who was visiting burst through a wave and said “Hey Parkey, wouldn’t that make a great photograph.” I’d been hearing that all my life… “Yeah, yeah, Wombat, sure it would.” But I was also reliving my childhood at the beach and felt something stirring. Narelle, who also grew up near the sea, was having the same sorts of feelings. We went out the next day, bought underwater cameras and spent every sunny day for the next two years at the beach.

We shot it all on a breath of air and in a way – it was the ultimate candid photography. No one even knew we were there as they battled to swim, surf, and survive the waves. We had no idea exactly what we were getting either as it was almost impossible to frame anything up. We would thrust the camera at arm’s length out in front and shoot a single frame, maybe two if we could stay down long enough, before being tossed head over heels by the power of the ocean.

Trent Parke

To learn more about the project and Parke and Autio’s process, read Trent Parke’s article at the Magnum website: The Seventh Wave

Minutes to Midnight

In 2003, Parke and Autio embarked on a 90,000 km road-trip around Australia for their Minutes to Midnight project, culminating in an exhibition and book which was published in 2005.

I’d been saving up for five years to make a long road trip around Australia. I sensed somehow something wasn’t quite right out there and I wanted to go see for myself. In the end, it was an article I read in a newspaper that finally got me going. A report that said that more than half of Australians felt the country had lost its innocence. It struck a chord. Certainly, it did seem a very different place from the Australia I had grown up in 20 years earlier.

Trent Parke

Minutes to Midnight provides a disturbing portrait of twenty-first century Australia. From the desiccated outback to chaotic life in remote Aboriginal towns.

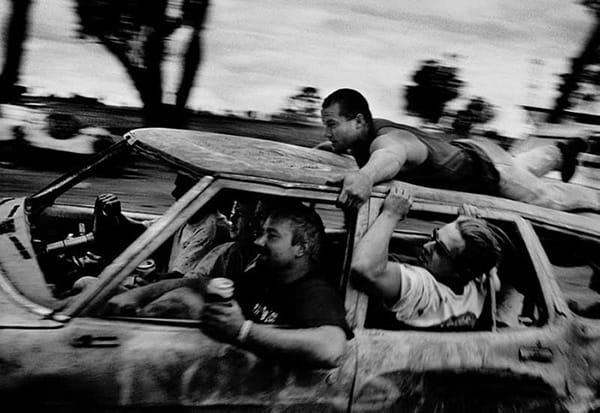

Ark broody skies, a landscape ravaged by bush fires, a wild-eyed hunting dog clutching its prize, reckless locals (or hoons) hanging out of a racing car.

Parke’s photos are dark and uneasy with a sense of mounting tension and uncertainty.

Fly by the seat of my pants, nothing arranged, but just go out and see what was happening in the country… What I do is I try and show it in an emotional way, not physically what the country looks like, but what it feels like emotionally to be living right now in this period of our life.

Parke was awarded the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography for his work on Minutes to Midnight.

Parke explains what message he was trying to convey through Minutes to Midnight:

The book is almost a fiction where I’m creating a story from these documentary pictures. It’s basically making a statement that the world’s going crazy.

Trent Parke

The Black Rose

The Black Rose is perhaps Parke’s most ambitious project to date. He began the project in 2007, drawing on childhood experiences and memories that he had blocked out for 27 years.

The Black Rose is the culmination of seven years of work. It started with a single line to a friend about the possibility of doing a project on the theme of home. Little did I know that seven years later, I would end up with hundreds of written stories, thousands of photographs, and 14 books, which dissected, basically, my entire life. Each book can be anything from, one page, two pages, to 500 pages. For me, it’s about how long a story takes to play out.

Trent Parke

The project title came as the result of a photograph of a plant found outside a motel room. The connection to nature – in particular, trees and plants – played an important role in Parke’s journey into his past.

Symbolically, The Black Rose is just death or the overcoming of a long journey. It is the search for absolute perfection, as the black rose does not truly exist. It is also referred to as black magic.

The Black Rose explores issues of life, death, and memory through a variety of subjects and objects: People, plants, animals, and everyday life in Australia.

I take all these moments and events that happen to me on a daily basis, things that normally pass people by, and chance meeting with someone, and dream from that night, all of those things come in and I look for some sort of connection between them, and then a narrative starts to form.

It’s always about finding answers to life. That’s what I’m looking for.

Trent Parke

Recognition

I use photography as a way to help me understand why I am here. The camera helps me to see.

Trent Parke

Parke has published four books, Dream/Life (1999), The Seventh Wave (2000), Minutes to Midnight (2003), and The Christmas Tree Bucket (2014). His work has been exhibited widely. In 2006, the National Gallery of Australia acquired Parke’s entire Minutes to Midnight exhibition.

Parke became a member of the street photography collective in 2001, followed by a Magnum Photos nominee in 2002. Parke became the first (and only) Australian to become a full member of the renowned Magnum agency in 2007. Parke has also won multiple World Press Photo Awards.

Photography Style

- Street Photography

- Social Documentary

- Gritty and contrasty, black and white

- Dreamy and melancholic

- Harsh lighting, deep shadows

What Camera Does Trent Parke Use?

For most of Parke’s early street photography, he used a Leica M6 and 35mm lens, later switching to an Elmarit-M 28mm lens. Parke also uses a Canon EOS 3.

For the Seventh Wave project, Parke used a Nikonos camera loaded with Ilford FP4.

His most recent projects have been photographed on medium format using a Mamiya 7 with color slide film.

Parke is an Ilford sponsored photographer. He uses Ilford FP4 for most of his black and white photos, although he has also used Ilford Delta for various projects.

How to Shoot Like Trent

What’s great about Parke’s work is that he captures images that can never be repeated and quite often not visible to the human eye, relying on chance and accidents.

For me, it’s all about chance, coincidence, mistakes… it’s all about discovery for me, those things that change your perception of where you’re going with the next body of work.

Trent has said that he will look back on a piece of work and wonder how it came about.

Here’s a video of Trent from 2014 where discusses his process, the importance of story, and what he’s looking for in his photos.

Still, looking for ideas on how to shoot like Trent? Here are a few tips on how to get as close to the Trent Parke’s look or style of photography as possible (without being Trent Parke.)

Chase light

I am forever chasing light. Light turns the ordinary into the magical.

Trent Parke

One of the key characteristics of Parke’s signature black and white look – which can be seen in Dream/Life and Minutes to Midnight projects – is his unique use of light to help bring his images to life.

You walk around at times thinking the whole world is a painting. Light is my work. That is my defining factor.

Parke masterfully plays with light, often using harsh shadows to convey mood and emotion.

Anyone can take a good picture, it’s about how you sequence that and how you take those pictures and make something more meaningful. That’s the secret, that’s the key, that’s the most difficult thing to do, and that’s the real art of what I believe I do.

In my latest work on the streets of Sydney, shadow and light is of the utmost importance. When figures walk into strips of bright sunlight from deep shadow they tend to blow out or glow before disappearing into the shadow again. I look for scenes in the street with this already happening or will chase light and wait for a scene to unfold. There is only the normal working of a print in the darkroom and no manipulation of the print to any other extent. It all comes down to the taking of the picture and a lot of waiting around as light moves fast.

Digital cannot handle a lot of the conditions that I use to shoot because I overexpose by massive amounts and I backlight something, then over process it in the chemicals so it has a specific look. Digital can’t handle it-pixels blowout…

Trent Parke

Shoot and shoot again

The more you practice, the better you’ll get and the more frames you shoot, the more chance you have of getting great photos.

To be a great photographer, you’ve gotta be fanatical, and as Parke says, “shoot a lot of shit.”

Usually, when I start a project, I’ll shoot for three or four weeks and shoot manically, and then I’ll arrange them on the wall or in my tent and I’ll print out little tiny pictures that I can look at, and subconsciously, without you knowing it, this is what I love about photography, things that have influenced your life when you’re growing up, they come through in other ways. I am fascinated as to what I am drawn to, to actually take the picture.

Trent Parke

The Moving Bus

To get his photograph of the bus for his Minutes to Midnight project, Parke shot over 100 rolls of film (3600 photos).

I went each evening, for about 15 minutes, when the light came in between two buildings. It happens only at a certain time of the year: you’ve just got that little window of opportunity. I was relying so much on chance – on the number of people coming out of the offices, on the sun being in the right spot, and on a bus coming along at the right time to get that long, blurred streak of movement.

If I didn’t get the picture, then I was back again the next day. I stood there probably three or four times a week for about a month. I used an old Nikon press camera that you could pull the top off and look straight down into because I was shooting from a tiny tripod that was only about 8cm high. I had tried to lie on the ground, but people wouldn’t stand anywhere near me.

I finally got this picture after about three or four attempts. I shot a hundred rolls of film, but once I’d got that image, I just couldn’t get anywhere near it again. That’s always a good sign: you know you’ve got something special.

Related Article: Street Photography Quotes

The fact that the images of the people on the bus have stayed sharp, and that you can see through them, is something that still baffles me. People can’t understand what the image is, or how I was able to obtain it, and I can’t work it out myself. It’s something that the eye can’t see when you’re walking along. It’s something that only photography can capture.

Trent Parke

Look for Action

My images are all real. I never set up photographs or ask people to pose in my personal work. Life is my subject matter. I am constantly watching life as still frames and moments. When I walk out my front door it’s like waking in a dream. I walk the streets watching everything, and I am in constant wonder.

Trent on his approach to street photography:

That’s how I approach street photography: watching everything. If I think something might happen, then I will hang around. But most of the time I’m rushing from one corner of the city to another, just looking for stuff.

Parke explains that it’s also important not to draw attention to yourself out on the streets:

I also don’t like to stand still because you attract attention to yourself. I’ve never been pulled up on the street and it is simply because nobody ever sees me. I’m there and I’m gone. If you spend too much time in a place you tend to start affecting what’s happening around you. And I just want to capture things as they are without influencing the action in any way.

Related Article: Daido Moriyama: From Snapshots to Stray Dogs

Even in his downtime, Parke can’t switch off, always looking for new photo opportunities:

You can be standing there and you’re just seeing stuff. All the time [I’m seeing] compositions coming together. The whole time I’m looking, everything is stopping and forming into still frames. Like people walking across the street and all that sort of stuff. Every tiny little thing… I find it very difficult to turn it off. If I’ve been out shooting for a couple of days, I can’t sleep for days on end because my mind is still going a hundred miles an hour.

Trent Parke

Make it Personal

Photography is a discovery of life which makes you look at things you’ve never looked at before. It’s about discovering yourself and your place in the world.

Parke explains how his photography isn’t about capturing photos “objectively” but rather photographing what is personal to him.

I’m always trying to channel those personal emotions into my work. That is very different from a lot of documentary photographers who want to depict the city more objectively. For me it is very personal – it’s about what is inside me. I don’t think about what other people will make of it. I shoot for myself.

Too many times, photographers concern themselves with what other people think and forget why they take photos. Try to remember that a photo is a self-portrait or a reflection of how you feel the moment you press the shutter.

For me, it’s all about [the] emotional connection. I love this country, love the people, everything about it. Whenever I travel overseas or have to shoot for Magnum in another country, I find I just make very graphic pictures. They occasionally might be visually interesting, but they sit on the surface. I am not really interested in any other country. Most of my projects last for years. I don’t feel I can achieve anything worth saying in a few weeks in a place.

I have always been interested in why I am drawn to something and why I eventually push the camera button. Most of it comes from memory, the subconscious, and events I experienced growing up. The beach, the outback, the suburbs, I could never leave any of it. So much to do here in Australia, there is just no time for anywhere else anyway.

Trent Parke

Decide on your Why

Ask yourself the following questions:

- How personal is my photography work?

- Do I express myself through my photos?

- How does photography help me better understand the world?

- What message am I am trying to say?

Everything that I have shot in my life has been autobiographical, it has been a part of my life, it has to mean something to me. If it means something to me, generally, it will have some sort of feeling on someone else.

Forget how many likes and comments you get on social media and use your photography to channel your emotions instead.

My work always grows out of what is affecting my life right now. I see myself as an average Australian and the issues that affect me are usually the issues that are affecting a lot of other people too. I want my work to comment on what it was like to live in this country during my lifetime.

Trent Parke

Other Resources

Recommended Trent Parke Books

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

- Minutes to Midnight (2014)

- Dream/Life (1999) *Wait for the price to drop

- The Seventh Wave

Prints available through Trent Parke’s Magnum Photo Shop

Trent Parke Videos

ABC Australian Story – Dreamlives (2002)

ABC News – Getting the Shot: Trent Parke (2014)

In-Public Interview with Trent Parke (2014)

Trent Parke Photos

Seventh Wave © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

Outback Northern Territory. Minutes to Midnight, 2004 © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

5m Shark, Cottesloe WA, 2003 © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

© Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

White Man, 2001, Minutes to Midnight © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

Christmas Eve, 2007, The Christmas Tree Bucket, © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

Camera is God, Adelaide, 2013 © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

New Year’s Eve, Gunnedah NSW, 2003, Minutes to Midnight © Trent Parke | Magnum Photo

You can see more of Trent Parke’s photos on his portfolio pages at the Hugo Michelle Gallery.

Fact Check

With each Photographer profile post, we strive to be accurate and fair. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the post.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Trent Parke’s Photography work then send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Please share this article

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it useful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

Finally, don’t forget to subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter for our latest updates.

Sources

Leica/CCP Documentary Photography Exhibition + Award Interview, 2001

Dream/Life, Cultural Development Consulting, Alasdair Foster, 2005

Interview with Trent Parke, Alasdair Foster 2007

Trent Parke: The Black Rose, Adelaide festival of arts, The Guardian, 2014

The photographer who made Australia his canvas, BBC, 2015

Trent Parke: The Black Rose, City Mag, 2015

The Seventh Wave, Magnum Photo, Trent Parke

Magnum Photo Biography

ABC Australian Story – Dreamlives (2002)

ABC News – Getting the Shot: Trent Parke (2014)

In-Public Interview with Trent Parke (2014)