Few photographers have lived and breathed the craft of photography with the singular devotion of Garry Winogrand. Regarded as one of the greatest street photographers (certainly the most prolific), the Brooklyn native’s obsessive pursuit of capturing life, provided an encyclopedic portrait of America between the late 1950s and early 1980s.

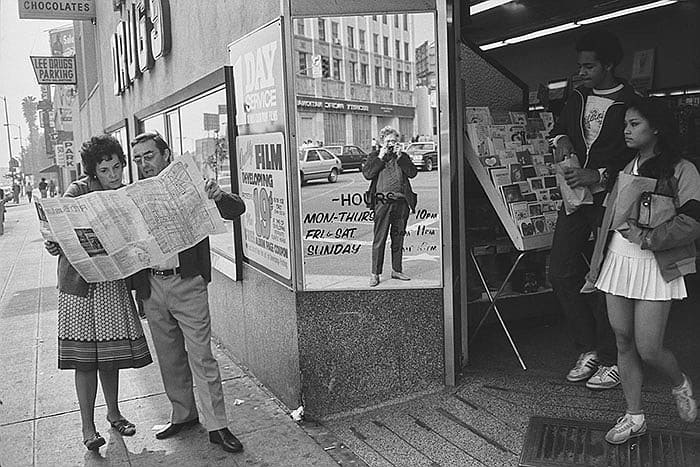

His images captured a bygone era: the explosion of youth culture, the New York of madmen, the early years of the women’s movement and the glamour and alienation of Hollywood.

Winogrand rejected the idea that his photos showed any narrative beyond what was captured on the surface. He stated in various interviews that they were not made to tell a story other than the one implicit in their own making.

Looking at his photos, you see the world in a millisecond and are left wondering what happens next…

More than thirty years after his death in 1984 (at just 56), Winogrand’s legend endures. His disinterest in technique was matched by his obsessive devotion to shooting every day.

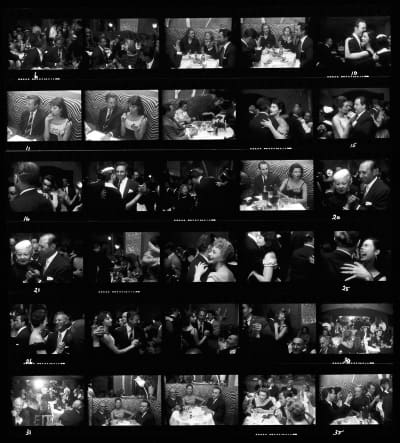

Winogrand’s impressive archive didn’t come from luck but hard graft and dedication to his craft. He took millions of photos during his lifetime (an estimated 5 million), sometimes shooting an entire roll of film as he walked along a single block (shooting around 400 frames every day).

When Winogrand died, he left behind a remarkable 6,500 rolls of unprocessed film, some 234,000 images.

Related: 46 Garry Winogrand Quotes for Better Street Photography

Although he’s best known today for his pioneering street photography work, Winogrand never liked being referred to as a “street photographer” as he found no real meaning to the term – he preferred to simply be referred to as a photographer and leave it at that.

I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.

Garry Winogrand

Table of Contents

Garry Winogrand Biography

Born: January 14, 1928, in New York City, NY

Died: 19 March 1984

Genre: Street, Documentary, Reportage, Advertising

Early Life

Garry Winogrand was born into a working-class immigrant family in the Bronx, New York in 1928. His parents worked in the garment industry. After finishing high school Winogrand spent a year in the US airforce before enrolling in a painting course at the City College of New York.

Winogrand then continued his studies at Columbia University in 1948, opting to study photography as well as painting. In 1951, he briefly studied under the great art director Alexey Brodovitch, who influenced the careers of many celebrated 20th century photographers including Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Robert Frank.

Professional Work

In the ’50s and ’60s, Winogrand first worked as an advertising photographer and freelance photojournalist.

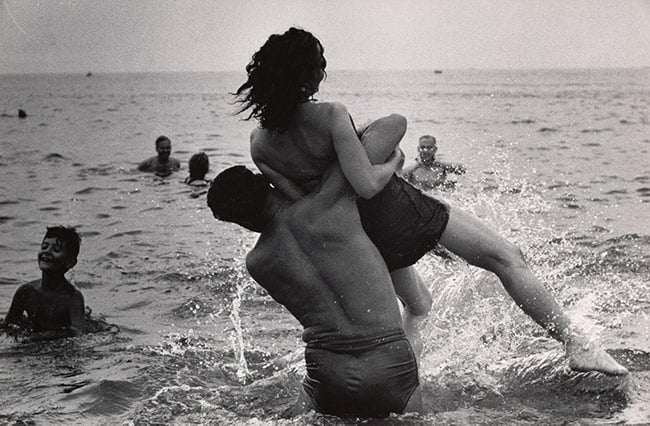

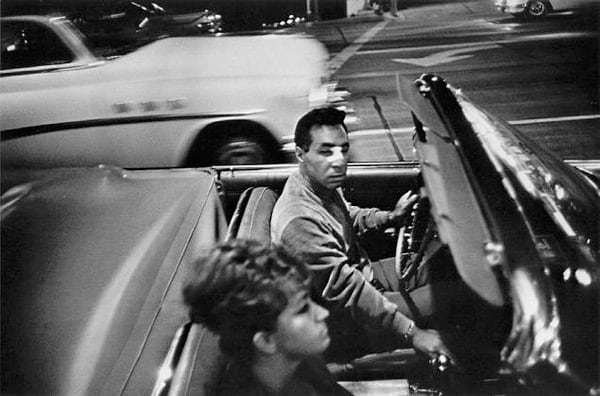

Early on in his career, Winogrand was interested in subjects that expressed themselves through movement, with sports and dance among his favorite. To Winogrand, the photographs could explain themselves, without interpretive commentary.

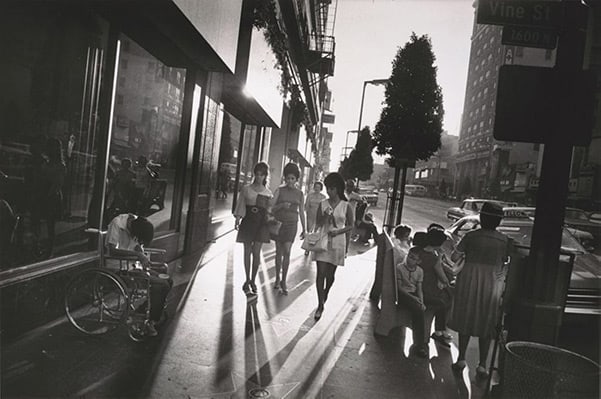

The 1960s

During the ’60s Winogrand would perfect his unusual style of “street” photography that would characterize his later work. Photographing the streets of New York, he portrayed passers-by with an immediacy and physicality rarely shown in still imagery of the time.

Winogrand’s rapid-fire shooting technique, wide-angle lens and frequently askew framing, became a hallmark of a radical new vision of photography that grew popular in the ’70s.

Sometimes I feel like the world is a place I bought a ticket to. It’s a big show for me as if it wouldn’t happen if I wasn’t there with a camera.

Garry Winogrand

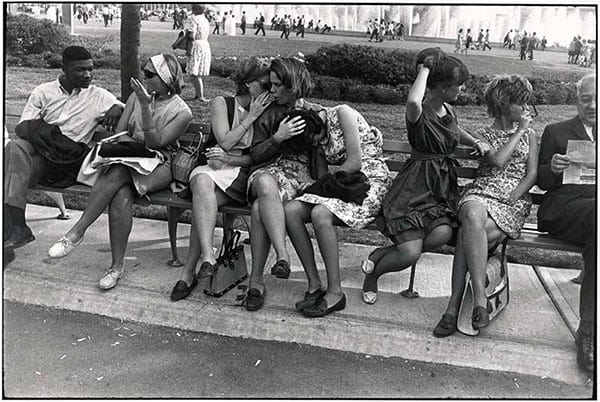

Winogrand would often shoot side-by-side with fellow photographer Joel Meyerowitz. While Meyerowitz, stalked the streets trying to be invisible, Winogrand didn’t mind being seen. Surprisingly though, many of his subjects only register his presence at the moment he presses the shutter.

In one of his best-known images, a chubby girl looks across at him curiously, while the other, an older girl, catches him out of the corner of her eye as she kisses her boyfriend. As is often the case with a Garry Winogrand photograph, you long to find out what happened next.

Recognition

In 1964, Garry Winogrand was awarded his first of three Guggenheim Fellowships for his “photographic studies of American life.”

Although Winogrand continued to shoot documentary and street photography throughout the ’60s, it was his commercial work that paid the bills. It wasn’t until 1969 when grants, teaching jobs, and print sales began to support him financially, freeing him up to devote his time to his personal projects. This work attracted the attention of galleries and photography institutes, with exhibitions soon to follow.

Winogrand published his first book, The Animals in 1969. The book was made up of a collection of pictures that observe the connections between humans and animals at the Bronx Zoo and Coney Island Aquarium.

Teaching

In the early ’70s, Winogrand moved to Los Angeles to pursue his own work. To support himself financially, he began teaching photographic workshops across the country. Teaching provided him with extensive travel opportunities and fresh scenery for the snap-happy photographer.

He would later go on to teach at Schools in Chicago, New York and the University of Texas in Austin.

Winogrand was generally uninterested in the students themselves, and his teaching was very laid back, preferring large classes. His workshops consisted of question and answers sessions, practical experience shooting on the street and photo review and feedback. He once stated in a workshop that “The student who can learn from a good teacher doesn’t need him.”

I highly recommended reading the following articles: My Street Photography Workshop With Garry Winogrand by Mason Resnick and Classtime with Garry Winogrand by O.C Garza.

Both men share their experiences from their time in the classroom with Winogrand and provide an invaluable insight into his photography techniques.

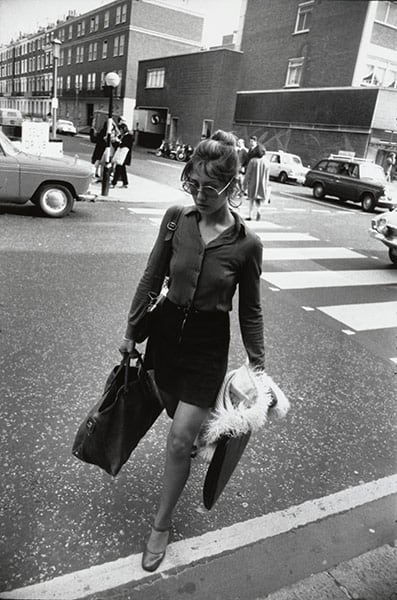

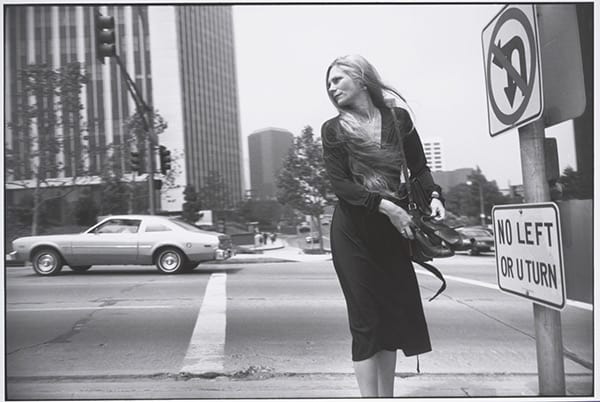

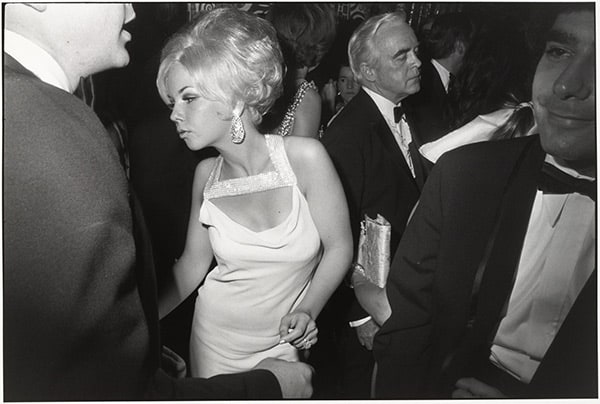

Women are Beautiful

His obsession with photographing women has led many critics to call him a sexist and chauvinistic objectifier of women. In Women Are Beautiful (1975), which is often credited as Winogrand’s most personal book (also dedicated to his wife and two daughters), he stated:

Whenever I’ve seen an attractive woman, I’ve done my best to photograph her. I don’t know if all the women in the photographs are beautiful, but I do know that the women are beautiful in the photographs… ‘Women Are Beautiful’ is a good title for this book because they are.

Garry Winogrand

Later Career

Winogrand’s career started to decline in the early ’80s. A new, conceptual photography movement – headed up by the likes of Cindy Sherman and Barbara Krueger – replaced the photography of Winogrand and co at art galleries.

His work was also at odds with feminists and many art critics of the time – even his early champion, MoMA’s John Szarkowski, who once called him, “the central photographer of his generation” now referred to him as a “has-been.”

I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and how we feel and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves …

Garry Winogrand

The aimlessness Winogrand sensed in America affected him profoundly, and this is evident in his later work. His altered way of seeing had a new sense of urgency about it, and he now obsessively shot the world around him.

In 1984, Winogrand was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer. He traveled to the Gerson Clinic in Tijuana to seek treatment but sadly passed away on the 19th March at the age of 56, just one month later after being diagnosed.

Legacy

Winogrand was among the generation of photographers that turned street photography into high art. He is considered an important influence on street photography and the snapshot aesthetic we see today.

Although the world lost a photography great in 1984, his work continues to live on for future generations to enjoy and learn from.

Winogrand’s photography has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art on several occasions, including his highly influential “New Documents” exhibition in 1967.

At the time of his death, Winogrand left behind approximately 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 developed but unedited rolls, and another 3,000 contact sheets. Many of these photographs were exhibited posthumously at a Winogrand exhibition at MoMA in 1988.

In addition to the above, the Garry Winogrand Archive at the Center for Creative Photography holds 100,000 negatives, 20,000 work prints, 30,500 color slides, and 20,000 contact sheets as well as Polaroids and several amateur short films.

Winogrand published four books: The Animals (1969), Women are Beautiful (1975), Public Relations (1977) and Stock Photographs (1980).

He has also received the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship three times: in 1964, 1969 and 1978.

Winogrand’s famous photographs include: Marilyn Monroe, with her skirt blown askew on the set of The Seven Year Itch, tourists at Dealey Plaza in Dallas following President Kennedy’s assassination, an interracial couple cradling baby chimpanzees and Norman Mailer’s 50th birthday party.

Winogrand’s Photography Style

- Form and content

- Snapshot aesthetic

- Non-stop, every day, all-day

- Wide-angle, got close to his subjects

- Not overthinking, reactive

- Mystery, open to interpretation

- Photograph within a photograph

Themes

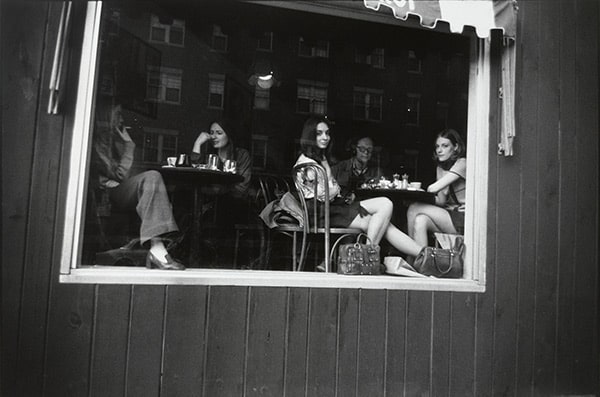

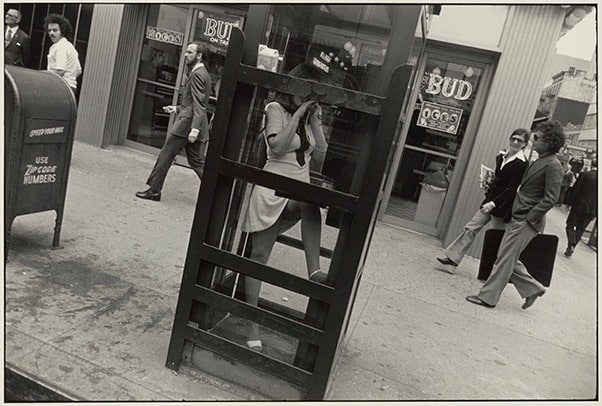

One of the major themes of Winogrand’s work is the concept of alienation, which can be seen even among his photos of crowded sidewalks and waiting rooms.

His subjects are typically lost in their thoughts, unaware they are being photographed. If they do hear the sound of his shutter, they look at the camera either with a sense of melancholy or with confusion.

Around them, the world tilts – Winogrand’s horizon line is seldom level – but there’s always logic to his compositions, an instinctive and experienced understanding of geometry and form.

Human Behavior

Winogrand’s photos are born out of his obsession with human behavior and are typically crammed with activity. Many times, Winogrand captured photographs within photographs or smaller narratives within the bigger picture.

His photos captured a lot of detail, due to his use of the wide-angle lens and deep focus, but he doesn’t tell his subjects’ stories for them. Instead, his photos have a sense of mystery about them, leaving it to viewers to create their own stories for his characters within the frame.

Influences

When it comes to influences he has mentioned: Eugene Atget, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank. In his classes and workshops, he would often discuss the work of Walker Evans, along with Andre Kertesz, Cartier-Bresson, Edward Weston, and Bill Brandt. Winogrand also studied painting, so no doubt he was influenced by the art world too.

What Camera Did Garry Winogrand Use?

Leica M4 and 28mm Lens

Winogrand was a dedicated Leica user. He preferred rangefinders to SLRs because he liked the simplicity and felt the SLR’s would often manipulate the photographer with framing and shot choice. His rangefinder allowed him to see the full-frame in focus, and past the edges of the frame.

Winogrand experimented with the 21mm, 28mm and 35mm focal lengths in the early ’60s. He felt the 21mm was the closest to his angle of attention, but it was too limiting due to the heavy distortion. So he settled on the 28mm as his lens of choice for most of his career. He also used a 50mm in his early days as a photographer.

The 28 is probably where the mechanical distortion is least limiting – much less limiting than a 21. It’s closest to the angle of attention. It’s pretty close to at least my angle of attention. Probably the 21 is more so, but it’s just extremely limiting. You have to use it very carefully.

Garry Winogrand

He opened his camera bag. In it were two Leica M4’s, equipped with 28mm lenses and dozens of rolls of Tri-X. The top of the bag was covered with yellow tabs. He told us he wrote light conditions on the tabs and put them on rolls as he finished them so he would know how to develop them. As we walked out of the building, he wrapped the Leica’s leather strap around his hand, checked the light, quickly adjusted the shutter speed and f/stop. He looked ready to pounce. We stepped outside and he was on.

Film Choice

When it came to film, he used Kodak Tri-X pushed to 1200 ASA. This allowed him to shoot at 1/1000th of a second so his photos weren’t blurry. As you would expect, this would change depending on lighting conditions.

We were using Tri-X film pushed to 1200 ASA, whereas the normal rating is 400. The reason was to be able to shoot at 1/1000th of a second as much as possible because if you made pictures on the street at 1/125th, they were blurry. If you lunged at something, either it would move or else your own motion would mess up the picture. I began to work that way after looking at my pictures and noticing that they had those loose edges, Garry’s were crisp.

Joel Meyerowitz, Bystander: A History of Street Photography

How to Shoot Like Winogrand

Every photograph is a battle of form versus content. The good ones are on the border of failure.

Garry Winogrand

It doesn’t matter what Winogrand was shooting he always tried to balance form and content, letting neither rule the other.

If you’re from the Cartier-Bresson school of thought (or technique) and a firm believer in capturing “the decisive moment” then you’re going to have to change your approach. Winogrand didn’t wait for the perfect shot, he found it.

For this section of the article, I have used a lot of quotes from Mason Resnick’s article: My Street Photography Workshop With Garry Winogrand. I highly recommend that you read the article to get a better understanding of Winogrand’s shooting style.

Related Article: Street Photography Quotes

Shoot and Shoot Again

The more frames you shoot, the more chance you have of capturing a great image. Winogrand would shoot on average 12 rolls of film every day (432 frames)… if you shoot that much then you’re bound to get one or two keepers.

This doesn’t mean you should “spray and pray” and hope for the best, just don’t be afraid to take a picture for fear of wasting a frame. Winogrand’s expert eye was no doubt nurtured by constantly shooting. As Michael David Murphy put it in his essay on Winogrand, he was in a way “the first digital photographer”.

As we walked out of the building, he wrapped the Leica’s leather strap around his hand, checked the light, quickly adjusted the shutter speed and f/stop. He looked ready to pounce. We stepped outside and he was on.

We quickly learned Winogrand’s technique – he walked slowly or stood in the middle of pedestrian traffic as people went by. He shot prolifically. I watched him walk a short block and shoot an entire roll without breaking stride. As he reloaded, I asked him if he felt bad about missing pictures when he reloaded. “No,” he replied, “there are no pictures when I reload.

Mason Resnick, My Street Photography Workshop With Garry Winogrand

Finding Photos

If something looks interesting then photograph it, and decide later whether it’s worth keeping. Winogrand wouldn’t hesitate to press the shutter, and would actively pursue his shots.

He was constantly looking around, and often would see a situation on the other side of a busy intersection. Ignoring traffic, he would run across the street to get the picture.

Mason Resnick

He was intrigued by people looking out at something outside of the frame that we couldn’t see.

I discovered things in that nothing.

Garry Winogrand

Get Closer

Winogrand photos had a sense of urgency and energy which only came from being close to his subjects, with many of his photos shot at arm’s length with a 28mm lens. He would often stand in the middle of a busy sidewalk and photograph people as they pass.

You would think this would be a great recipe for a bust lip. Incredibly, people didn’t react when he photographed them. It surprised me because Winogrand made no effort to hide the fact that he was standing in [their] way, taking their pictures. Very few really noticed; no one seemed annoyed.

Winogrand was caught up with the energy of his subjects and was constantly smiling or nodding at people as he shot. It was as if his camera was secondary and his main purpose was to communicate and make quick but personal contact with people as they walked by.

Mason Resnick

Here’s a clip of Winogrand shooting in the streets:

Don’t Force your Photos

Winogrand preferred candids and never posed his subjects. His photos are moments played out in the public which he happened to chance upon.

I like to think of photographing as a two-way act of respect. Respect for the medium by letting it do what it does best, describe. And respect for the subject by describing it as it is. A photograph must be responsible to both. I photograph to see what things look like photographed.

Garyy Winogrand

Edit Without Emotion

Winogrand never developed film right after shooting it. He would wait a year or two so he wouldn’t have any emotional attachment to the photos, allowing him to view each frame with a fresh and critical eye.

Sometimes photographers mistake emotion for what makes a great street photograph.

You make better choices if you approach your contact sheets cold, separating the editing from the picture taking as much as possible.

Garry Winogrand

“If I was in a good mood when I was shooting one day, then developed the film right away,” he told us, I might choose a picture because I remember how good I felt when I took it, not necessarily because it was a great shot.

Mason Renwick

Framing your Photos

Winogrand also discouraged “shooting from the hip” as Resnick recalls:

I tried to mimic Winogrand’s shooting technique. I went up to people, took their pictures, smiled, nodded, just like the master. Nobody complained; a few smiled back! I tried shooting without looking through the viewfinder, but when Winogrand saw this, he sternly told me never to shoot without looking. “You’ll lose control over your framing,” he warned. I couldn’t believe he had time to look in his viewfinder and watched him closely.

Indeed, Winogrand always looked in the viewfinder at the moment he shot. It was only for a split second, but I could see him adjust his camera’s position slightly and focus before he pressed the shutter release. He was precise, fast, in control.

Mason Renwick

Think in Black and White

Winogrand is best known for his black and white work, although he didn’t ignore color completely. Towards the latter part of his career, his main camera would be loaded with Tri-X whilst his second camera body would be loaded with color film. He mainly used black and white film because it was cheaper and far easier to develop at the time.

Today with digital photography it’s easy to convert images to black and white, but it’s also possible to set your camera so that the images are converted for you.

To get the Winogrand look today try this:

- Set your digital camera to RAW + Fine JPEG and change your profile to Monochrome.

- Change the ISO to 1200 and set the camera to shutter priority at 1/1000th.

- Although Winogrand used a 28mm prime, you can get away with using your kit lens or zoom set at a 28mm equivalent (18mm on Nikon DX).

- Turn image review off. Don’t concern yourself with getting the image perfect. As Winogrand said, a great photograph is often on the verge of failure.

- Use matrix metering. Set focus to continuous AF, single point (or use zone focussing instead.)

- Once you’re done shooting, don’t look at your images for 3 months. Seriously. If this doesn’t phase you then wait longer (up to a year!)

Garry Winogrand Resources

Disclaimer: Photogpedia is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases.

Recommended Books:

- The Animals (Museum of Modern Art, 1969)

- Women Are Beautiful (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975)

- Winogrand: Figments from the Real World (New York Graphic Society, 1988)

- The Man in the Crowd: The Uneasy Streets of Garry Winogrand (Fraenkel Gallery, 1999)

Garry Winogrand Videos

Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable

Garry Winogrand Documentary – Part 1

Garry Winogrand Documentary – Part 2

Garry Winogrand at Rice University

Garry Winogrand – Women are Beautiful Photos

Garry Winogrand Photos

More Garry Winogrand Photos:

MoMA | Garry Winogrand

Whitney Museum of America | Winogrand

Garry Winogrand Image Search (Google)

Fact Check

With our profiles, we try to be as accurate and fair as possible. If you see something that doesn’t look right, then contact us and we’ll update the article.

If there is anything else you would like to add about Winogrand’s work, and his life then feel free to send us an email: hello(at)photogpedia.com

Link to Photogpedia

If you’ve enjoyed the article or you’ve found it helpful then we would be grateful if you could link back to us or share online through twitter or any other social media channel.

The website was put together so we can all learn from masters like Garry Winogrand. The more links we have to us, the easier it will be for others to find the website.

Finally, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram and Twitter to get information on our photographer profile updates.

Sources

Garry Winogrand: Innovator in Photography, The New York Times, 1984

Facts Within Frames: Garry Winogrand’s Last Work, The NY Times Magazine, March 1988

Garry Winogrand, New York: MoMA, 1977

In Winogrand: Figments from the Real World. New York: MoMA, 1988

The photographic legacy of Garry Winogrand, BBC, March 2013

Garry Winogrand and the Art of the Opening, The Paris Review, 2013

the Photographer Who Captured the Madness of the Mad Men Era, Vanity Fair, 2014

Rediscovering Garry Winogrand’s Vision of America, Huff Post, 2017

The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, The Guardian, 2018

Sontag Susan: On Photography, 1977

Winogrand Figments from the Real World, New York The Museum of Modern Art, 1988

The Man in the Crowd: The Uneasy Streets of Garry Winogrand, Fraenkel, 1999

Icons of Photography: The 20th Century, Prestal, 1999

Garry Winogrand, Metropolitan Museum, New York, 2013

Bystander: A History of Street Photography, Laurence and King, 2017

Garry Winogrand at Rice University, National Gallery of Art, 1977

Visions and Images: Garry Winogrand, 1981

Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable, American Masters, 2018

Class Time with Garry Winogrand, O.C Garza, 2007

My Street Photography Workshop with Garry Winogrand, Mason Resnick

Garry Winogrand Profile at Museum of Modern Art